The sweet smell of success led to a scary moment for fans of the rooster.

Panic struck in fall 2013.

Word spread like wildfire: “The plant that makes Sriracha might shut down,” it went, and those who’d become hooked on the sauce with the Rooster on the bottle began to stock up, unsure of where their next fix would come.

That year, Huy Fong Foods had processed 100 million pounds of fresh chilis over the course of its harvest season.

To meet skyrocketing demand for its hot sauce, Huy Fong Foods had opened a gleaming new 650,000-sq-ft state-of-the-art facility in Irwindale, California a year before just to produce Sriracha (one of three sauces it makes). At the time, the condiment could be found almost everywhere—from every counter space at then rising star David Chang’s original Momofuku noodle bar to a flavor of Lay’s potato chip. That year, Huy Fong Foods had processed 100 million pounds of fresh chilis over the course of its harvest season—crushed fresh, with in an hour of harvesting. The new factory could produce 7,500 bottles of sweet chili pepper sauce an hour.

The Sauceman Cometh: Huy Fong Foods founder David Tran.

The monument to the popularity and appeal of the Rooster Sauce should have been a capstone moment for David Tran, the founder of Huy Fong Foods. But some nosey neighbors in Irwindale objected to the “odor” of Sriracha production, moving the city to file a lawsuit against the company seeking its closure. Tran’s lawyer, Rod Berman, an expert in intellectual property rights, had become at home filing infringement suits against the many copycats popping up, but this was new territory.

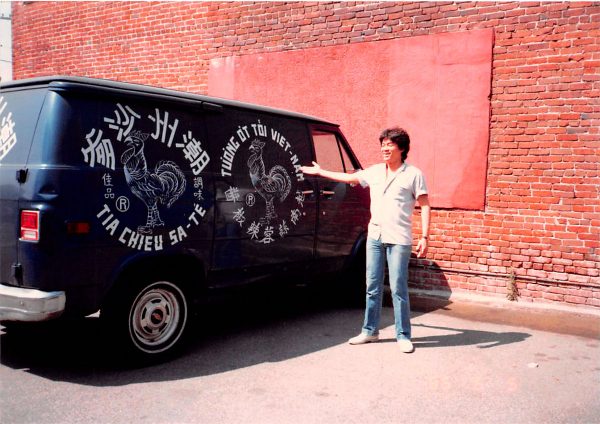

The factory was only about a half-hour drive down The 10 from the place where it all began for Tran. But the road looks much longer when you compare the trucks bringing in ripe red jalapeños, 21 tons at a time to the old blue Chevy van Tran started with in Chinatown in 1980.

Well before the Chevy van—the one that David Tran painted the now-familiar rooster logo on himself—, back in Vietnam in 1975, Tran made a cooked chili sauce from serranos called Pepper Sa-te sold in recycled baby food jars by bicycle. In 1979 he left Vietnam on a Taiwanese freighter and made his way to Los Angeles. The name of the freighter incidentally: Huey Fong. By 1980, with Tran noticing he was missing the spicy sauces from home, the Sa-te was back in production and along with it over the next couple of years Sambal Oelek, Chili Garlic, Sambal Badjak and, of course, Sriracha Hot Sauce.

Man with a Van: David Tran circa 1980.

It’s not much of a stretch to say that Sriracha was the biggest thing to happen to hot sauce in more than a century. The story of hot peppers and hot sauce has always been one of crossing oceans and continents—from the chilis that made their way to Europe and then Africa and Asia from Central America and the Caribbean to the people planting peppers and making sauce. Tran stands as influential a figure as Edmund McIlhenny, who planted his tabasco seeds from Mexico in Avery Island, Louisiana in 1867.

The raw pepper sauce Tran concocted and liked so much that he put the rooster—his zodiac symbol—on it, was created to his own tastes, he told Whalebone Magazine through longtime Huy Fong executive Donna Lam. The flavors—a meld of geography and tastes and history—that made up Sriracha came together in David Tran’s original production facility in Chinatown. The recipe was a few parts what he knew from making sauces in Vietnam, maybe one part homesickness and a good deal of necessity: He was really trying to find a way to earn an income to support his family. The mother of invention was using fresh red jalapeños grown in the warm Southern California sun in a sauce with a lineage of at least two countries in Southeast Asia.

Tran began putting some serious miles on the old Chevy, driving north to San Francisco and south to San Diego to make deliveries.

Red jalapeños are actually the same pepper as green jalapeños—just left to ripen and mature on the plant longer, developing more of the heat-inducing capsaicin and a richer flavor. Most jalapeños are picked when the fruit (yes it’s a fruit) is just at the beginning of the ripening process and still green—it takes some time and patience for them to develop the deep red hue that colors Sriracha. Tran paid a premium for the harder-to-come-by commodity and it paid off.

The Sriracha scratched an itch for more people than just Tran. A lot more people. He began by selling direct to noodle shops and Asian restaurants locally in Chinatown who had been missing the sweet hot fire of home, made and delivered fresh. Then Tran began putting some serious miles on the old Chevy, driving north to San Francisco and south to San Diego to make deliveries.

Before the ‘80s were out, Tran had traded the van for real delivery trucks and a distribution deal and moved to a 65,000-sq-ft facility in Rosemead, California. Then less than a decade later Huy Fong expanded that into the building next-door, a 170,000-sq-ft former Wham-O toy-making factory. Frisbees, hula hoops and slip-n-slides had given way to rows of meticulously lined and stacked blue 55-gallon drums filled with freshly ground red chili peppers.

All of this incredible growth had come with the company doing almost nothing to promote itself—at least in terms of advertising and marketing and publicity. David Tran, now 75, has always been somewhat camera-shy, and reluctant to talk to the media (in fact, for this interview the answers to Whalebone Magazine’s questions were emailed back in all caps by Donna Lam who has been Huy Fong’s executive operations officer since 1986, most preceded by “DAVID STATES…” as in “DAVID STATES HE HAS NOT REALLY TASTED THE THAI SRIRACHA.”). As the company boomed in the ’90s and early 2000s, employees joked that Sriracha was the “secret” sauce, with the double meaning that the company didn’t really do anything to tell people about it. That attitude might have counter-intuitively accounted for at least some of Sriracha’s stratospheric success with many people discovering the cheerful red bottle with the green cap on a shelf and mistaking it for an obscure East Asian brand.

Huy Fong Foods broke ground on its Irwindale headquarters in 2010, doubling the combined square footage of the two Rosemead production facilities when it opened in 2013. But the rising Rooster might have had more in common with Icarus than the Phoenix.

The battle over the odor of Sriracha production raged from that fall into the spring. An Irwindale judge found “a lack of credible evidence” to support locals’ complaints of breathing trouble and watering eyes linked to the new factory, which had been suspect to begin with since they came at a time outside harvest when peppers were not being crushed. Also not crushed: The hopes and dreams of the loyal Rooster fanatics. In May, the City dropped its lawsuit.

When asked by Whalebone what turned the tide in the threat to close the plant, David states, “WE DID NOT TAKE ANY STEPS TO APPEASE IRWINDALE.” And affirms, “‘WE DIDN’T DO ANYTHING WRONG.’”

There have been other bumps in the road along the way—can you even imagine what is involved in making hot sauce from 100 million pounds and counting of fresh chilis?—but when asked what makes Sriracha Sriracha, “DAVID STATES NO MATTER WHAT CHANGES, WHAT MAKES THE SAUCE IS USING ‘FRESH CHILI PEPPERS.’”

THE OGs

Although David Tran claims to not really to have tasted a Thai sriracha hot sauce (saying he just makes his sauce the way he enjoys eating it), his Rooster sauce takes its name and inspiration from the original chili-garlic sauces produced in the seaport town Si Racha (the preferred anglicization of the placename) in the Chonburi Province in central Thailand, where many have not even ever heard of the American version.

Sriraja Panich

Most agree that Thanom Chakkapak or her father, Gimsua Timkrajang, originally came up with the basis for this style, but hers was a sun-dried chili sauce, as opposed to Huy Fong’s raw version. In 1984, Ms. Chakkapak sold the company to Thai Theparos Food Products, one of the largest food companies in Thailand.

Shark Brand Sriracha Chili Sauce

The Shark Brand is the real deal, going back to the roots of sriracha sauce, adds more heat and tang than the Sriraja Panich version and is thinner and less sweet than Huy Fong’s. It’s wildly popular in its home country and is the preferred brand of some persnickety American chefs like Pok Pok’s Andy Ricker.

THE COPYROOSTERS

You know how they say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery? David Tran kind of agrees. For whatever reason, he never trademarked the term “Sriracha” as Edmund MchIlhenny trademarked “tabasco,” and maybe that was a good thing. Huy Fong Foods has never spent a dime on advertising but clearly benefited from the knock-offs and essentially unlicensed versions from the likes of Taco Bell and Subway, which all helped to take the brand beyond a pho shop staple to a household name. With a shrug, Tran calls it “free advertising.”

The courts have ruled that “sriracha” by itself is too generic a term to trademark, and while the Whalebone Legal Dept. says Tran might have been able to trademark “sriracha sauce” or “sriracha hot sauce” had he tried, he did not. (He did however trademark his rooster and distinct green cap.) But this is one reason why you see sriracha (with a small s) sauce in familiar shaped bottles everywhere—from a Trader Joe’s Dragon Sriracha that really roller skates around the edges of trademark infringement to craft versions with zodiac tigers in white reminiscent of the rooster to entries dipping into the ring from the American “Louisiana-style” OGs like Frank’s Red Hot, Texas Pete and, yes, Tabasco.

NEW KID ON THE BLOCK

While good old slinging sauce from a van formed the basis of its growth, Huy Fong’s most meteoric success might have been driven by the rise of social media. The bottle is damn photogenic, and Tran even told Whalebone that he really noticed how popular Sriracha was when he began to follow social media around 2013.

Three Mountains Yellow Sriracha (one of three variations the Thai producer makes, but the one that has captured the public imagination) is the latest hot sriracha to give rise to dedicated Instagram accounts (such as @hot_blonde_sriracha, which features the yellow-capped Three Mountains bottle cozying up to food items and people) and YouTubers emoting breathlessly with a passion once reserved for the Rooster. Made from the yellow Thai burapa chilis from Si Racha, the sauce hits some richer, earthier notes than other pretenders to the throne and brings a fair amount of heat.