That New New

This story isn’t about hot sauce.

Well, not just hot sauce. It’s about what happens when you start over from scratch.

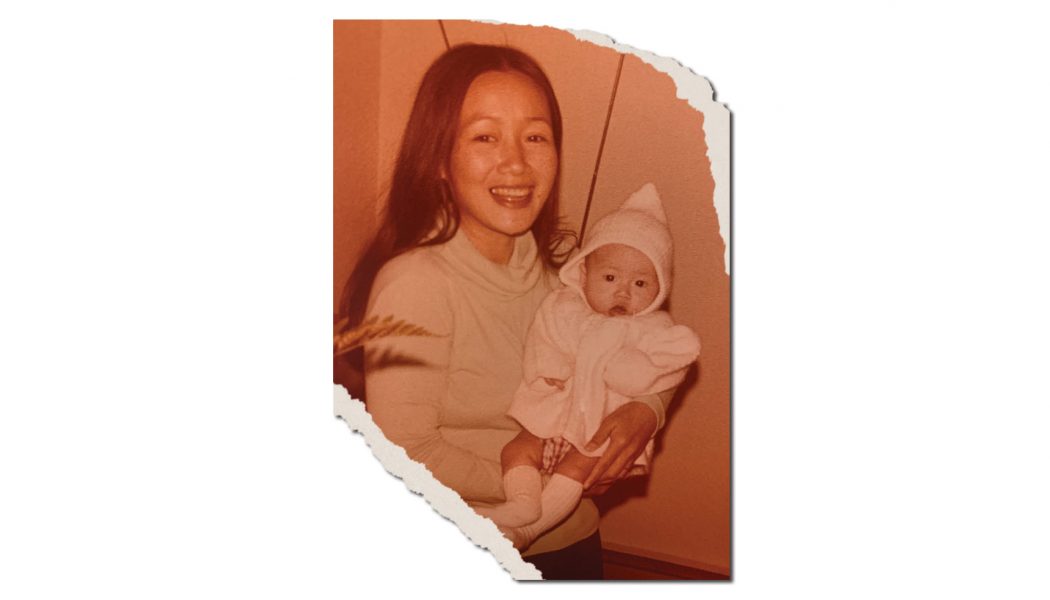

His first attempt ended in failure when first he faced Thai pirates on a fishing boat and then when he was captured by the VC and put in what the government euphemistically called a “reeducation camp.” The attempt may not have been a total failure though, for that was when he met Mai, who hailed from a well-to-do Buddhist family. Mai had heard about a boat that was leaving and tried to get on it—she ended up in the same camp as Vinh. The next year they made another attempt, together this time, and sailed away from the strife of Vietnam landing in a refugee camp in Indonesia. Life was not easy in those years, and they gained an appreciation for every ingredient they could scrounge when mealtimes came, a situation neither of them were used to. They had each other and were soon married, and not long after, Mai became pregnant. Their daughter Lisa was born there in the Indonesian refugee camp.

Lisa tells Whalebone Magazine that her parents’ approach to food really grew out of that experience. “They just got really resourceful,” she says. Her mom missed the flavors of home. “They didn’t have the right ingredients so she’d play around with whatever they could get at the refugee camp and I think that spurred them to be interested in food as not just sustenance, but something to experiment with.”

When people are backed up against a wall, they get pretty creative.

The conditions that led to Vinh and Mai leaving Saigon may have been traumatic, but the little family that resulted was happy. “People don’t just leave the country and the only homes that they know for no reason. There’s a reason why they had to leave and it’s because they felt like there was no future,” Lisa says. “When people are backed up against a wall, they get pretty creative and they get, if anything, more optimistic about the future, and so my parents really had a lot of great memories from the refugee camp.”

The family finally arrived in Tigard, Oregon, a suburb of Portland, in 1981. With no other background besides his religious education from seminary school—a path he’d abandoned—Vinh began working at restaurants to get by, washing dishes and then moving up through all the basics, learning things like how to use a meat slicer or properly hold a knife. But he was still a long way away from opening his own Vietnamese delicatessen. He worked as a machinist for Boeing for a stretch, and then when he was laid off, the opportunity to serve the local Asian community with some tastes of home presented itself.

Lisa says the guidance for opening the delicatessen came from her aunt and uncle who were running one up in Vancouver, BC. “Nobody was making Vietnamese ham, nobody was making Vietnamese pâtés for sandwiches and so forth,” she says. “My aunt and uncle came down to show them how to make these deli meats so that we could bring it down here because nobody was doing it in Portland.”

The family opened Tân Tân Café & Delicatessen in Beaverton, Oregon in 1998, at first just serving the specialty deli meats and treats from Vietnam they knew would feed the community in more ways than one. Then within a few years, Tân Tân (the name translates to “new new,” or “new beginnings” approximately) slowly but surely grew. “Gradually throughout the years it expanded from just being a deli where we sold meat by the pound with a little mini-grocery store next door, to adding one or two soups that would utilize and showcase our deli products and then it just expanded into a full-blown restaurant,” says Lisa. It’s now something of a cornerstone of the community and one that has provided many solace along with their soup. The line of Vietnamese sauces from Tân Tân, also evolved naturally. “We didn’t set out to make sauces,” says Lisa. “Our family started out making meatballs and deli products and the sauces were just a side item that we would serve with the meatballs, or that we would serve as a condiment for things for people to bring home and cook.” Then people began coming in just for the sauces. “It started with the Mom’s Hot Chili Sauce because it was just this hybrid chili sauce that my mom had made. It’s a lemongrass base with some chili peppers and it was fried in oil, so it’s a reddish color and people would want to buy it in a tub—they would want a tub of Mom’s Hot Chili Sauce because when we served things to go, it was 32-ounce soup containers.” Not even thinking about it, the restaurant would fill a deli tub of hot sauce and charge $5.

We didn’t set out to make sauces.

So in 2017, Lisa launched a line of three Vietnamese sauces (a hoisin, peanut and now a vegan “fish” sauce sit alongside Mom’s Hot Chili Sauce) which are the very first vegan-certified and gluten-free Vietnamese sauces on the market. Something Mom can be pretty proud of, having grown up a Buddhist vegan in Vietnam.

Mom’s Hot Chili Sauce is on the thicker side, and has the layered textures and flavors you might expect from a sauce with such a rich background: habaneros and Thai bird’s eye chilis give an initial kick but this is not a banger. It’s a balanced and savory sauce with the base of fresh lemongrass adding some depth and brightness with flecks of whole chili seeds in there and an oily element that makes it perfect for drizzling in pho or mixing into a spicy stir fry.

The unique flavors come from Mai’s original recipe and the spirit of experimentation she learned in Indonesia. The tried-and-true process came together in the kitchen through years of making the sauce for the restaurant. “As we layer in the ingredients during the cooking process, you taste the different layers that bloom in your mouth,” Lisa says, “so it’s not just a flash in the pan where you just taste it and it’s spicy but then it goes away. It has that lingering heat and then the more you eat it, it gets a little bit more heated, but then you can also taste a little bit more of the sweetness. There’s a lot of nuance in the sauce.”

Lisa is now a mom, too, but she says the Mom of Mom’s Hot Chili Sauce is definitely her Mom. The image on the bottle is actually drawn by a local artist from a picture of Mai riding a bike way back when. “My Mom’s truly everybody’s Mom. And we have a lot of kids who are on student visas here, students or people working in here at Nike or Intel, which is close to town, and they’re away from their families and everybody comes in and calls my mom ‘Mom,’ it’s funny.”

Lisa never forgets the ordeal that her parents went through and appreciates all it took to reach this “new beginning.” When she asks her parents if they would do it all over again, leave Saigon and risk everything to start over, their answer is a measured, “no,” despite how appreciative they are to have their lives. “Because at the time, they didn’t know what death was,” Lisa explains. “But being on a boat for four or five days, a tiny little fishing boat in the open ocean and having to face Thai pirates the first time around, and having family die who tried to escape. It’s just they didn’t know what death was and if you ask them now, they wouldn’t have done it.”

But of course, they are happy they did make the journey. Lisa finds it appropriate that Mom’s Hot Chili Sauce is born out of the memory of what they were missing while in the refugee camp. She says her mother would always tell her, “when she was pregnant with me, she would crave all the sauces, so it’s funny how it worked out that I’m actually making the sauces that she craved back in the day.”