Where the Green Palms Grow

Photos and story by Ellie Shrube

Walk down any street, sit down at any bar, or travel on any ferry and it’s inevitable that you’ll meet a Bahamian who has lived through a hurricane. Down here, in this archipelago wrapped in every shade of teal, hurricanes are part of normal life. They are expected.Every year from June through November, locals wait. For them, it’s intuitive to know how to board up a house, plan out shelters, and survive for a few weeks without power or perishable food. But few people could have been prepared for Dorian.

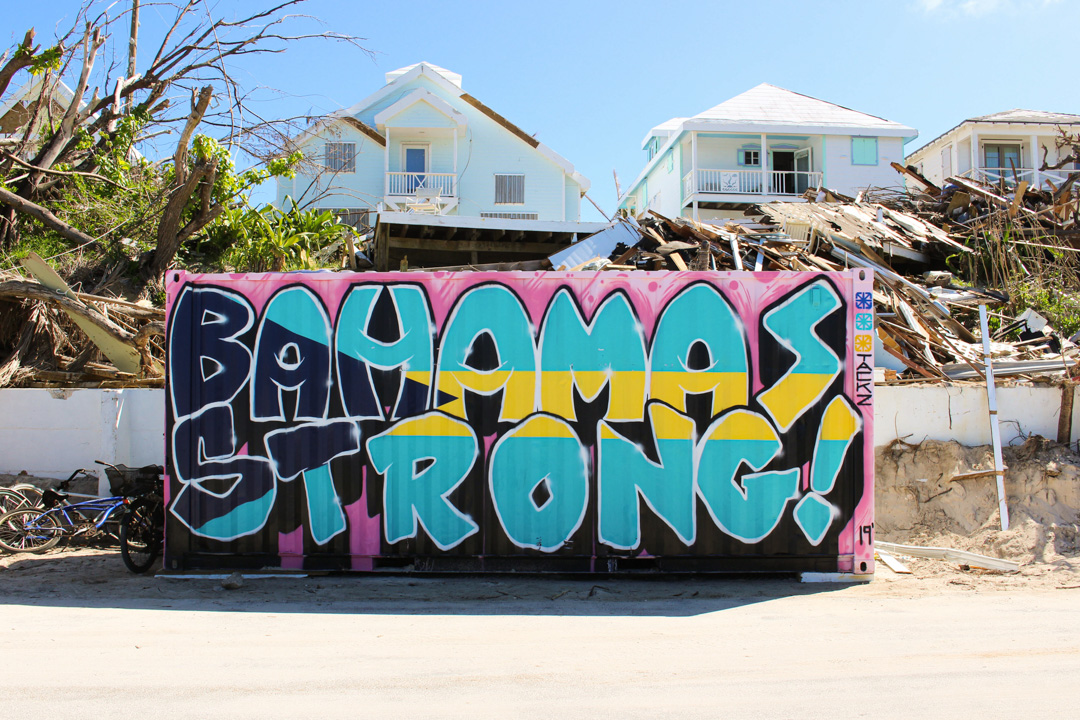

On Labor Day Weekend 2019, Category 5 Hurricane Dorian made landfall on Elbow Cay, a barrier island off Great Abaco. Drifting at only three miles per hour, it gained momentum from the warm waters and low wind shear of the Caribbean, with sustained winds at 185mph and gusts clocked as high as 220mph. It sat there for sometime, seemingly comfortable as if it were enjoying a day at the spa. Tornadoes grazed the islands and stripped anything in its path. Storm surge rose to 20 feet, satellite images of lighting looked like bioluminescent jellyfish stinging its prey. After devastating Elbow Cay, Dorian moved on to the largest city in Abaco, Marsh Harbor, leveling it, then off to Grand Bahama where it remained stationary for nearly 36 hours, eventually making its way north.

Hurricane Dorian was the most powerful hurricane in the Atlantic Ocean on record when it made landfall. Until Dorian, Hurricane Floyd was the most disastrous storm to strike modern day Abaco in 1999, but a local told me that Floyd was a “light rain storm” in comparison to Dorian.

How did Dorian become such a monster?

The story of its origin begins far, far east in the Sahara Desert. The National Hurricane Center’s satellite images picked up one of the largest Saharan dust plumes of the season blowing off North Africa. The interaction between the hot, dry air of the Sahara and the cooler, more humid air from the Gulf of Guinea to its South forms what’s known as the African easterly jet, which blows from east to west across Africa. Within this jet, tropical waves can from, and when they interact with the warm equatorial waters of the Atlantic as it moves west, it triggers columns of warm moist air to rise from the ocean. This literally creates a perfect storm—thus giving life to Dorian.

The aftermath of this storm is almost unfathomable. There are about 20,000 residents who call the Abaco islands home. After the storm, nearly everyone had to evacuate, over 90% of homes were damaged or destroyed and while the media states 56 deaths, talk to a local and that seems drastically under-reported—the death toll is likely well into the thousands. Because the storm surge was so high, many people unfortunately drowned or were washed away. And in Haitian shantytown communities like Pigeon Peas and The Mud where the housing is not sustainable, many were unable to survive a storm at this magnitude.

When I visited Abaco right after Dorian on Halloween weekend, I was honestly in complete shock at the devastation. Memories flooded my mind and sadness sunk in. My family has had the privilege of visiting this collection of islands for 50 some years. Some of my family loved this paradise so much, they stayed. My best memories are here, and some of my first big life experiences were here.

To Hope Town

To come back to this place was emotionally difficult. It truly looked like a bomb went off—houses splintered into sticks, yachts bellied-up in the middle of the road, mattresses skewed in between the Abaco Pines, debris becoming a new form of nature, and the palm trees brown and battered, their green sway now gone. Places I once knew were unrecognizable. But still, on the boat ride from Marsh Harbor to Elbow Cay, the water seemed bluer, the sky seemed more vibrant. Beauty still exists in the chaos.

The water seemed bluer, the sky seemed more vibrant.

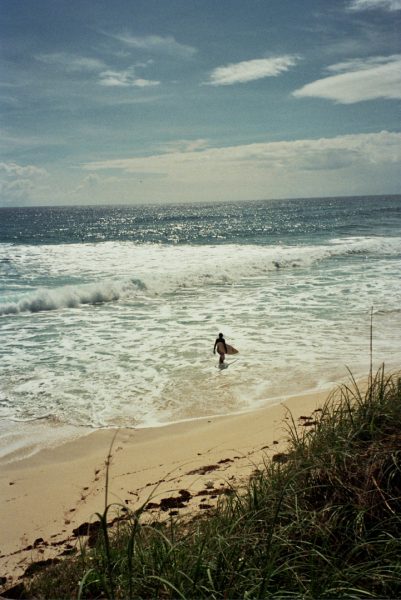

Abaco might be one of the most unique places on earth. First, it is a waterman’s oasis; marshland, shallow lagoons, sand banks for miles, deep sea, surf, and the fishing and diving are world-class. If bonefishing, billfishing, bottom fishing, spearfishing or diving for crawfish interests you, you’d never leave. Beyond sport, there are little keys floating throughout the Sea of Abaco; home to Green Turtle Cay, Man-O-War, Guana Cay, Spanish Cay, Scotland Cay, and Elbow Cay, where the beautiful Hope Town is located—also home to the world’s last functioning kerosene-burning lighthouse.

While the landscape of this place is beyond ethereal, it is the spirit of the people that brings many people back every year. Bahamians are genuinely some of the most welcoming and kind-hearted people I’ve had the pleasure of meeting. Big-smiled, hard-working, and funny as hell is the nature of a Bahamian, with resilience running through their veins. But for me, what makes Bahamians so exceptionally different is the demographic make-up. Elbow Cay is the only place I have ever been where it does not matter what the color of your skin is.

The island is only six miles long, and the community is very tight-knit. Many of the locals go back generations, and share similar heritages. They cross paths everyday, work together, and because there is no local government, they make decisions together. They judge by personality, not by what they look like or where they came from. Here, people live in harmony.

During the four days I spent on Elbow Cay, I talked to quite a few locals. Hearing their stories from the storm left me in dismay, like I had just watched a Tarantino film. I was told one man on Guana woke up to his house flipped upside-down, so he crawled out from an opening and got into his truck, flooring it into the rubble to burrow himself through the worst of it.

The Eye of the Storm

John Pinder, an eighth-generation Abaconian, was in his home with his family during the storm.

“I hear this huge bang, and I look up and there was light; come to find out that it was the house next store that hit my house, getting mixed up in the tornado. I tell my wife and kids to get into the bedroom, but they were already in there by the time I turned around, and I turn back and a big chunk of the roof came off, and the room started spinning.”

In the chaos, Pinder had to act. When the eye came over, he ran out the back door with his 6-year-old and 6-month-old daughters, wife and two potcakes (Bahamian term for a mutt dog), and took them to Firefly Resort down the street. He got them safely inside, then realized he forgot to bring his 14-year-old parrot, Abaco, so he ran back home and buried her in the rubble. As Dorian’s eye moved on 20 minutes before dark, the wind picked up again. Pinder had to run back to Firefly in 100mph winds, “You plant your feet and grab onto whatever, a telephone pole if you can.” Miraculously, everyone survived, including Abaco the parrot.

You plant your feet and grab onto whatever, a telephone pole if you can.

John Pinder

The Mackey sisters, Delphine and Brenda, were also at Firefly during the storm. Like Pinder, the sisters have rich heritage in The Bahamas. Originally from San Salvador, they moved to Hope Town in the eighties when their father got a job as the lighthouse keeper.

During the storm, the sisters were with several others in a house that was on the brink of demolishing.

“The house felt just like a boat. It was the weirdest thing I’d ever seen.” Delphine and Brenda, along with 30 others, shared a house, sleeping on tiled floor for two days. After the storm, the sisters stayed on the property in a good-standing home.

The Mackey sisters though, have been working tirelessly since day one of the aftermath.

“We’ve been cooking everyday. And it’s tiring, but you know what? It keeps your sanity. You don’t get to think about what’s next.” Now, the sisters make meals for everyone working the South End of the island—250-300 meals three times a day, almost everyday.

The house felt just like a boat.

The Mackey Sisters

When I asked Delphine what her hope is for Hope Town, she responded, “I would love to see it come back as what it was, but I don’t want it to see it come back like the Florida Keys [or Baker’s Bay]. And that’s my big fear, is that’s what’s gonna happen.”

Her response seems to be the general sentiment of the locals. Abaco has such a sublimely authentic culture, and it is disheartening to hear that newcomers and foreigners are hoping to develop the island on their terms, all to make a profit.

The Aftermath

Driving around the island, I saw people working on all sorts of projects—tarping roofs, clearing debris, rebuilding homes, and salvaging whatever they can from their pre-Dorian life. People work hard and long. Second homeowners came back as well to get involved and bring over supplies from the States. There is a Command Center set up with a select few folks appointed to call the shots. They’re still sorting out how to go about this mess, but most importantly, they’re fervently working to make the island exceptional again. Egos and politics will always get in the way, but that should not deter the true goal to rebuild better and stronger than before, together.The interesting thing about the aftermath is that everyone has had a job in some shape or form, some jobs more significant than others from a societal standpoint, but nevertheless, each job is necessary, and everyone works together.

“After the hurricane, everyone came together; rich, poor, black, white, Bahamian, American…everyone came together. And everyone just became, even,” said Delphine.

The island’s only current bar “On Da Beach” is where locals might go after a long day’s work for a few Dark and Stormys or a beer. Whatever is available. After all, it’s still island-time.

After weeks of non-stop work, some of the local guys decide to take out a lent boat to go diving. We head South toward Tilloo Cut. The boys work like a school of fish in the water—holding onto a rope trolling off the stern, everyone on the lookout, and when someone spots something, the stronger diver will go check it out.

Dylan Thompson, a ninth-generation Abaconian, dives down and comes back with the biggest lobster I’ve ever seen. Later on, they see something, a massive mutton snapper. Three of the guys try to spear it with no luck. Dylan dives in again. A minute later, he shoots to the surface bear hugging this mutton. Everyone cheers and it’s game on. We go drag for conch after, and come back with a decent amount, ready for a feast. On the ride home, everyone has a job. Dylan cracks the conch, Ashton and his brother SJ clean the conch, JR prepares the conch, and their cousin Velli cleans the fish. Sean Thompson, Dylan’s cousin, is the captain and also, the hype man. The whole day was filled with good fun in true Bahamian fashion. Though as we trolled the kaleidoscope seas along the shoreline, the view is still bleak and eerie. When we were diving, debris was nestled in the seagrass and a golf cart became home for a few yellowtails.

Come Together

Media reports depict the Bahamas as a war-zone, with massive controversy in hopes of pitting people against each other, purportedly for recognition. When I was there, I saw complete unity and shared solace. Of course, when you’re on a destroyed island long enough, there will be deplorable things said and arguments had. But, it does not waiver the spirit of the people and the desire to rebuild.

When I asked Pinder if he plans to stay here, he replied, “Hope Town? All my life. I’ll probably die here. Yeah, man, this is home. I spent my younger years traveling a lot, but realized there’s no place like home. And even though this place was destroyed, the wild life is coming back; there’s schools of fish, schools of birds, and the greenery is coming back. And there’s more work than anyone can handle.”

Tom Hazel is the operator of the charming and historic Abaco Inn, which has already re-opened the restaurant and bar on November 9th.

Firefly hopes to reopen in March.

Everyone knows and loves Tom. He is a tireless worker, greets everyone with an unalloyed smile, and is completely dedicated to the well-being of Elbow Cay and its residents. If he ran for Mayor it would be a landslide victory.

Tom Hazel

As I sat across from Tom, the sun pouring through a battered roof above his head, he shared with me his frustrations with the lack of government involvement, but heavily emphasized that that the community and second homeowners are of more help than the government could ever be. Delphine felt similarly.

Like all of the residents on Elbow Cay, Delphine is worn out and frustrated. She will admit that even if the government was well organized and proficient, the challenges created by Dorian are nearly impossible for any bureaucracy to manage. To put it in perspective, a November 15 report by the Inter-American Development Bank stated that impacts pf Dorian “comes out to over a quarter of the country’s GDP—or the equivalent of the US losing the combined economic outputs of California, Texas and Florida.”

Though for me, I’m confident that the people of Elbow Cay will prevail. Their spirit is wildly strong and their love for the island in the sun is deep-rooted. As the the coconut palms and sea grapes sprout new growth, so will Hope Town. It is an opportunity for a rebirth.

As Delphine, Brenda and I sat on their patio, overlooking scathed villas and the Sea of Abaco, Delphine pointed out to me a weary palm, brown from the wind burn, “but look, there’s some green beginning to grow!”

How to help

Due to lack of government involvement, the wonderful residents of the Bahamas greatly need support. There are several non-profit organizations currently on the ground, and they are vital for the continuing relief. If you feel moved to support, please donate through Samaritan’s Purse, Convoy of Hope or Abaco Rescue Fund.