You Don’t Know Jack

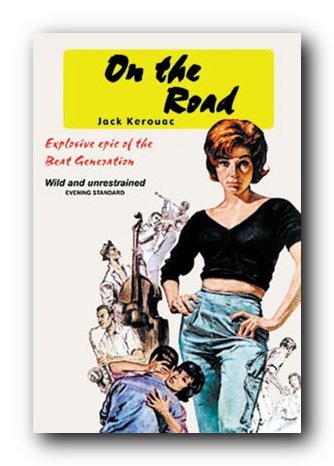

My wife used to own A Little Shoppe of Flowers, a florist in Ozone Park. Which, of course, doesn’t mean jack to you.Unless you’re a Jack Kerouac aficionado. Then, you know that name from the sign in the photo of Kerouac’s 1940’s home that appears on many of the websites you’ve visited. Or you came by to take a selfie with the plaque on the wall next to the shop’s back door stating that Jack used to live upstairs with his folks while sketching out On The Road.

And if you made a “Jack pilgrimage” back then, maybe you met me. You might have stopped into the shop with a question or two, and if I was there, we spoke a bit. See, I know a Kerouac thing or two. I’ve done some research. And, more important, my grandfather was Jack’s tailor when he lived in Ozone Park; a good buddy’s dad drank with him, even though Jack kinda’ kept to himself; and I knew his old landlord as a kid.

When the folks from American Zoetrope came to Ozone Park to do research for a Kerouac biopic, naturally they came to Little Shoppe. Seems they didn’t know jack about Jack’s time in Ozone Park. But I did.

“Lenny, I have some of your people here.”

It was Paul, the retired police sergeant who helped run the Lindenwood Volunteer Ambulance Corps upstairs from the flower shop. He sounded…bemused.

“My people?”

“The Kerowackians. The freaks you humor with stories. They want to talk about Kerouac.”

Paul nicknamed every person and group. He had a talent for it. He had given that name to the Kerouac fans that came by so often. They were almost always either college kids in hippie garb (even though Jack was a beatnik, not a hippie) or older dudes in dungarees, chambray shirts and corduroy blazers accompanied by women in granny dresses. The hippies often carried back-sacks with bongs visible through their colorful material. The older group always carried well-worn paperback novels.

I hadn’t gotten a nickname from Paul yet.

“They want to talk to someone with roots in Ozone Park who can tell them things about Kerouac being here,” Paul said. “That’s you Ozone Man.”

Now I had one.

“Look, I’m busy at the office.”

“I don’t think you want to blow this off. They say they’re with Francis Ford Coppola’s company. They have a clipboard of papers, cameras, sketch pads. They need some history. I can’t help them: I’m a Greenpoint kid. They need you. They say whoever helps them will be thanked in the credits of the movie they’re gonna’ make.”

Now that was altogether different. That was very exciting. These were not your everyday Kerowackians. These were movie people! I thought that I might be able to give them some tidbits that would make it into the movie. Seeing something that I had told them about brought to life on the big screen would thrill me beyond belief. I had to go, instantly, work be damned.

“That sounds very, very cool. I’ll be there in 15 minutes.”

The Zoetrope folks had really fancy business cards emblazoned with a sketch of an old building with lightning bolts coming out of the antennae atop its cupola. The cleverness of that was not lost on me.

“I like that. Coppola…cupola. Nice”

“That’s the Sentinel Building in San Francisco,” one of them told me. “Francis and George own it.”

“George?”

“Lucas.”

Oh.

There were three of them: a thin, well-dressed guy, my age, with a Clark Kent face; a frumpy young guy with a beard, not stylish back then; and, of course, a hot young chic in hot young clothes. The older guy’s hands were empty, the girl carried a steno pad, and the frumpy guy carried everything else—two 35mm cameras, a video camera and a big leather duffel. Poor guy.

“We need to recreate a lot of things to make this movie. And we want to be somewhat accurate. But we can’t find any pictures. Can you tell us what things looked like in the 40s? Can you paint us a picture,” they asked me.

I chuckled. “Yeah, I think I can do that. I can also tell you a lot of stuff. And answer questions. What I don’t know, my Mom does.”

We started with the room we were in, which, in Kerouac’s time, and mine, was Sam’s Drug Store. It was, of course, an old-fashioned drug store, with dark brown wooden display cases with glass tops and wood breakfront cabinets lining the walls. In the back, just about where my wife’s checkout counter was, was Sam’s register, with Sam behind that, behind glass, in the formulary. I laid out every inch of it for them.

“How do you remember?” they asked. “It closed in 1969.”

“I’m around since ’60. And I was here a lot. I dunno’ why. I remember when the Beatles first came out, Sam used to come down from his perch and pick me up and sit me on the counter and play this game with me showing me magazines and asking me which Beatle was which. He swore he couldn’t tell them apart, and he would always get their names wrong and I would correct him and he would still get them wrong. This happened over and over. I would get exasperated and he would laugh, and his accent really came out when he laughed. Then he would say he only liked Ringo and I would argue with him about that. I was a ‘Paul guy’ even then. And that would make him laugh even harder. I was a teenager before I realized he was kidding the whole time.”

The Zoetrope people looked stunned.

“Oh, my God. You can tell us what Sam looked like!”

“Oh, of course.”

I let them stew a bit as I faked pondering. Then I simply said “J. Jonah Jameson. ”I paused again, waiting for one of them to catch on. But none of them did.

“He looked just like J. Jonah Jameson from the old Spider-Man comics. Flat top crew-cut. Gray sides, black top. Same face, too. But no mustache.”

“The accent?”

“German. Not very thick, but it was there.”

“Are you sure? You were just a kid.”

“I watched Hogan’s Heroes,” I answered. But there were those blank faces again, even on the older dude.

“Yes, I’m absolutely sure.”

Then I showed them the pay phone that was still in the same place as it was when the place was Sam’s. I knew Jack used to get phone calls on that phone from Allen Ginsberg and others when he lived upstairs and Sam was his landlord. Well, not that very phone. It was a wooden phone booth in Jack’s time, with a black rotary phone.

“How do you remember that?” the girl asked me.

“I used to play in the booth as a kid. Sam and my Mom were a little paranoid about it: they didn’t like when I snapped the booth closed. Sam said I could suffocate.”

There was that blank look again, but only on her face. I told her to go watch some old George Reeves’ Superman clips on YouTube.

“You know, I could even get you the phone number,” I said, half goofing, half bragging.

“How?” The girl asked with disbelief. So I called my Mom right there in front of her. See, my Mom has the same phone book, perfectly preserved, for 50+ years.

“VI-3-9822,” I said.

“Ginsberg wrote VA-3-9822 in one of his letter,” she said.

“Ginsberg was wrong. Or he wrote sloppy. The exchange here was Virginia.” Two blank looks again, one glimmer of recognition.” It was abbreviated “VI.” My number as a kid was VI-8, etc. You don’t forget this stuff.”

The Zoetrope folks behaved as if they had entered a shrine. They sketched the molding on the doorways, unchanged for all these years. They photographed the tin ceiling, also unchanged.

Next, we went upstairs from the flower shop, into the ambulance corps office in the apartment that was once the Kerouac family’s. The Zoetrope folks behaved as if they had entered a shrine. They sketched the molding on the doorways, unchanged for all these years. They photographed the tin ceiling, also unchanged. In fact, photographed everything. They drew the floor plan and theorized where the kitchen table and furniture were. They seemed surprised by the dog-leg staircase that led to the apartment. The young guy said Jack should have incorporated that staircase in a story somewhere. But apparently didn’t.

When they took photos from the window in the corner room that they explained was Jack‘s bedroom, they marveled that they were standing in the very space where Kerouac sat up late at night conceiving On The Road. I think I did, too. They wondered what Jack would have seen out that window in the ’40s. I did my best to help them visualize that, noting that there were scores and scores of trees back then that are now gone. I told them that Balsam Farms, a big dairy farm, was straight ahead only two blocks away back then, and that Kerouac could surely see the barns. I told them that the newspaper articles saying how Jack would look north out his window at the Crossbay Movie Theater were bullshit because Crossbay Blvd. dog-legs right, like the stairs, and was lined with trees taller than the houses back then. There would’ve been no way on earth to see the theater before they widened the road and took out the trees in 1972.

My Mom knew that Kerouac loved the place because he was my grandfather’s customer, and he had said so.

Then the Zoetrope folks wanted to take a walk. And they filmed it. I described the old Crossbay Blvd. to them in more detail with its tree-lined center and sidewalks. I told them what was in all the storefronts on the boulevard, with a little help from my Mom, by phone. Turns out there was a German Deli called Block Island next to Sam’s in the ’40s, pre-me. And my Mom knew that Kerouac loved the place because he was my grandfather’s customer, and he had said so. Finally, we took a walk up 133rd Ave. to what they told me would be Dean Moriarty’s house, if the guy had really existed. That one was new to me. The young guy filmed the older guy asking me questions, and me gabbing, the whole time.

As we walked back up to Crossbay Blvd., one of the Zoetrope guys asked if I knew anyone that would remember the 40’s name of the bar across the boulevard where Jack and his dad drank, and Jack sometimes played piano. It had been called Glen Patrick’s Pub for a lot of years at that point. Seems they had visited it earlier, and no one there could tell them what it used to be named. Someone told them it might have been “Doxsey’s” in the ’40s.

“You’re kidding me,” I laughed. “It was McNulty’s Bar and Grill. From the day it opened until Jimmy Jr. sold it, it was always McNulty’s. Doxsey Place is the name of that little street right there. It was never called Doxsey’s. It didn’t have a pseudonym. Ever. It was just McNulty’s. I can’t believe those knuckleheads couldn’t remember. I can still see the sign in my mind’s eye.”

That got them kinda’ excited, too, and I described the green neon shamrock that said “McNulty’s” and blinked between the unblinking words “Bar” and “Grill” on the long vertical sign at its corner. I told them that that same shamrock was also etched on the window. And as I described it, the girl sketched it, and it came out pretty spot on.

He said Jack used to come into the bar late sometimes and get a big teapot filled up with beer from the tap.

“I knew a guy who drank with Jack and his Dad there sometimes,” I volunteered.” He was my friend’s father. His nickname was Dublin John, and Jack joked that it should be Doublin’ John. He was a big scotch drinker and he said Jack was a big beer drinker. He said Jack used to come into the bar late sometimes and get a big teapot filled up with beer from the tap. He also said Jack kinda’ kept to himself. Maybe that’s why that’s the best story I ever heard from anybody around here about Jack Kerouac.”

They had a bunch more questions. I told them the ethnic makeup of the neighborhood in the 40s: Irish, Italian and Jewish immigrants and their American born kids. I described the “little kid’s library on Jerome Ave.” that Kerouac wrote about. Another old-fashioned place with wooden wall shelving. It had a really cozy little reading room for kids in the back that I liked a lot. I spent a lot of time there as a kid. They showed me a photograph of where they thought that library was. It showed the wrong place. I directed them to the right storefront to visit.

Then I showed them where Nobel Laureate Gerald Edelman lived in the ’40s, catty-corner across Crossbay Blvd. from the Kerouac’s, and I said I always wondered if he and Jack ever met.

Finally, I told them that my grandfather Carmine was Jack Kerouac’s tailor.

“How do you know?” I was asked.

“I asked him if he recognized the name once I learned about Kerouac living here, and he did.”

“Did he say anything else?”

“Yeah. He said Jack’s hair was too long. He was surprised because Jack used to get his hair cut at George Cotrone’s barbershop a few doors away from McNulty’s, and George usually gave guys a ‘nice-a short’ haircut. And he said Jack didn’t like any break in his pant leg.”

“What?” the older guy said. “I never read that.”

“He wore khakis a lot,” the girl added.

“Yeah,” I said. “He got them at Shep’s Army-Navy Store up on Rockaway Blvd. Shep told me years ago. But he called them chinos.”

They seemed skeptical.

“I was an English major at NYU, a long time ago. Somewhere, I learned that Ginsberg referred to Kerouac as the Wizard of Ozone Park. Being from Ozone Park, I looked into that a little bit at the Bobst Library, and I learned that Kerouac lived here for a while. I had never heard that before, so I started asking old-timers about him. And a couple remembered him. Not many, but I got some scraps of information.

“You seem to know a lot we didn’t, and we’ve read everything.”

“Yeah, it’s good we connected,” I said. “Cause, you guys didn’t know jack.”

The documents I signed said I would be thanked in the final credits if and when the film got made. Which may not mean jack to you, but, as an aspiring Wizard of Ozone Park, is a big deal to me.