Cause Equals Action, or Was It the Other Way Around?

We asked 30 people who we admire to each interview one person they admire. That’s the concept behind the Interview Issue presented by Design Within Reach.

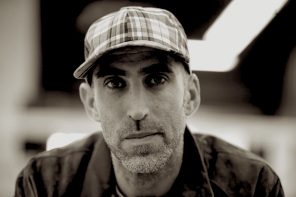

Pro surfer Dylan Graves chose Waves for Water Founder Jon Rose

It wasn’t supposed to be my job.

Dylan Graves: You were a pro surfer, and you once told me it was on a surf trip that it dawned upon you how you wanted to help and how Waves For Water, your clean water efforts organization, started?

Jon Rose: In all honesty, the whole inception of the organization was pretty selfishly motivated, but not selfish in a bad way. I’m very candid about that because it wasn’t supposed to be my job. My whole thing was like: Okay, my pro surfing career is coming to an end. I don’t know what I’m going to do with the rest of my life yet or the next chapter. I want an excuse to go back to Indonesia twice a year. I want to be able to go back to some of those places that I love to surf. No matter what job I step into next, I want to be able to have that, and genuinely I thought, What a cool sort of excuse or platform to do that in helping those places at the same time.

It’s like whatever job I was going to have I was going to be like, “Yeah, well, you know what? I go twice a year with this organization I founded, which is a cool thing. It’s me and my crew.” I was going to rally all the boys and just be like, “Hey, let’s do this. Let’s go back on surf trips a couple times a year and help all these places while there and not make a big deal out of it.”

I chose water because it seemed solvable to me. It was something I could wrap my head around. I’m like, “You know what? I can bring solutions that already exist or I can learn how to at least organize the digging of a well or build rain catchment systems.” You know, stuff like that, I had been interested in already, so it just made sense.

Before I got to go to the little island I had planned on going to, we had to do an overnight in Padang on the way back and the quake hit that night.

Then it turned into what it did because of the experience in Padang on the first trip and being caught right in the eye of a disaster and seeing first-hand what I could do without even trying. It was so loose, man. I was like, “Yeah, I’ll call it Waves for Water.” I bought 10 filters with my own money, went on a boat trip to Mentawai. Before I got to go to the little island I had planned on going to, we had to do an overnight in Padang on the way back and the quake hit that night. Next thing you know we’re helping collect bodies.

Those hours on the ground there, I was able to have a focus even though I had no experience. I just went into survival mode and was like, “Well, I have a task. My task is to build these water filtration systems for people that I feel need them and so be it.” Those hours on the ground I had a crash course of crazy, crazy education around the water cause itself, around disaster relief, around my own capacity to perform in those situations. Stuff I just didn’t even know about myself because I had never been put in that situation.

I thought I was going to go for two weeks and I stayed for two years.

After that, it was just a polarizing line in the sand. It was just like, “I don’t even know how to not do this. This is like I can’t stop thinking about it. I don’t understand. I barely tried and those ten filters helped thousands of people. What if I really tried? What if I just really gave this thing my all and actually like applied myself.” Of course, it was also perfect timing, too. because I was getting divorced, and I didn’t know what I was doing with my life and I was real free in that sense.

I came home from Indo, I raised more money just through friends to get 200 more filters, went straight back to Sumatra, implemented those. I didn’t even have a real organization yet, I just had the idea and the name but I was obsessed with just getting that task done. Then two months later was Haiti and I got the opportunity to go down there. I thought I was going to go for two weeks and I stayed for two years and that’s where I really developed everything that we do and why we do it and how we do it. It was an organic evolution.

DG: When did Waves for Water officially start as an organization?

JR: I incorporated the name when I had that initial idea, which was in the spring of ’09. I didn’t get us certified as a 501(c)(3) which is the categorization within the government for a non-for-profit organization. I didn’t even apply until I think mid-2010 but I was already working in Haiti. I basically had got the name incorporated and then set up a bank account, bought those ten filters. That was in spring of 2009.

Fall is when I went to Indo on that Mentawai trip, bought 10 filters, super relaxed about it, I didn’t even need to have certification because I wasn’t even getting donations, it was just like my own thing. I bought those filters and went on that trip. Then January of 2010 was Haiti and that’s when I went down there and once I was down there, I knew that this is what I wanted to do with my life. So, I then applied and got the certification and all that kind of stuff.

DG: From my experience, recently being involved with the Caribbean efforts with Waves For Water, I feel, you become instantly passionate and just dive straight into the most essential thing to what people need, especially in a crisis. How has Waves for Water evolved from the initial start in 2009?

JR: A lot’s changed. It’s just like any company that you’re going to start, not like I’ve started a lot of companies, this is my first one, but anything that you’re going to start, whether it’s an organization or a company or anything, a project that you’re working on, it’s like you have your initial concept and then you have your first phase, your first task to get through and then so on and so forth. It just grows and grows and grows and then it evolves into what it’s going to be.

I’m a surfer, and I’m dealing with all these big swinging dicks of the aid world.

For me, those two years in Haiti, that was my college. That was like my MBA program around this. It was the epicenter of the aid world at the time. I got a first-hand look at all the other organizations, what they do, how they do it, and I came with a really fresh perspective because I was not from that world. I’m a surfer, and I’m dealing with all these big swinging dicks of the aid world and the development space, the development sector. There’s a lot wrong with that sector and there’s also good stuff happening too so I won’t write it off completely but for me, I didn’t owe anybody anything. I didn’t have to answer to anybody. It was just me, by myself, in Haiti, figuring it out day-by-day and I was keeping it real simple.

I’m like, “Okay, well, these people need this. Now let’s go find the area of need that I can sort of relate to like how big is the community?” Hold on one second … “Can I handle this level of implementation?” So, I go through that checklist and then I go out every day and go out to that place and I would implement and I would learn how to implement and the difference between distribution of supplies and a true implementation of a program and how much the difference there is in the results of those two things and how I wanted to build the organization moving forward. You start super grassroots solo runnin’ and gunnin’, making mistakes, and then learning all the way to now where we are a global organization. We have programs in 27 countries. We have partners like BMW and Nike and the UN and the US Military, so in some ways, it’s changed in the best case scenario of an evolution. It’s just grown and we’re able to do what I was doing by myself in Haiti in those early days in 27 counties in different capacities. Also, incorporating rain catchment, also incorporating the digging of wells.

We’ve now added in an M&E aspect to our program, which is monitoring and evaluating. It’s basically the follow-up but it’s a full-scale program. I hired an infectious disease doctor to run it and she’s the one tracking and analyzing all of the data based around what we’re doing and the work we’re doing. Now there’s hard numbers, there’s hard facts on impact that we’re making. These are all things that maybe I didn’t necessarily have in the early days because I didn’t have the resources to do it. That’s how it’s changed. It’s changed. Tighter ship. It’s growing in the best way and we’re still making mistakes all the time but we’re just getting better. Our standard gets better every year. I’m constantly challenging us to keep things simpler, always to remember to stay simple, but we do grow in our capacity. Our capacity to implement better, our capacity to track the follow up better, our capacity to team build better. We grow in that but I want to keep everything super streamlined at the same time.

There’s nothing better in the world for what it actually does and what it actually costs.

DG: I wanted to include the breakdown of the filters and what sort of impact each one can have on a community just so the readers can understand a little bit like how impactful each filter is. Could you explain?

JR: I’m of the thought that it is one of the greatest technological advancements of our time. If you want to simplify it, the common term is “bang for your buck,” there’s nothing better in the world for what it actually does and what it actually costs. It’s remarkable. It’s actually so, so incredibly impressive.

You’re talking about something that filters on a higher level than what the EPA standard is for bottled water and provides a million gallons of water. That’s the potential of it. Just like a human has a life expectancy, a filter does too. Now you can treat the filter bad or you can treat your body bad and you won’t live as long as you’re supposed to, so it’s not perfect. It’s not a perfect solution. Nothing’s perfect. For the thing to reach its potential or if it does, you’re talking about decades of support for somebody who would never have access to that otherwise.

It’s a game changer. The ripple effects of implementing one of those filters is not just helping somebody with the baseline value of their health and drinking clean water but from an economic perspective, they’re saving money not buying water anymore. They’re not paying for medications for their kids who get sick by the water they’re drinking. The kids aren’t missing school so there’s an education uptick. There are all sorts of other ripples that happen just by introducing this one solution into the equation. You got all that and the filter itself, it provides enough water per day for 100 people if you’re using it at its capacity.

When you start breaking it down and you start looking at all the boxes that need to be checked, you’re like: Okay, is it easy to use? Yes. Is it cost effective? Yes. Does it filter well, does it do what it’s supposed to do? Yes. Does it have a long life? Yes. It’s got almost all the boxes checked, and there’s other solutions out there, but for me, I’m just baffled at how amazing this thing is.

If you do the math on a filter being used at its capacity then you’re talking over 100,000 people would be benefiting from that amount of filters.

DG: No, it’s very impressive. I was blown away prior to going down for our Caribbean trip. I was looking on the website, learning about the filter, and I’m like, “Wow. That sounds insane.” But until I held it in my hands and was really grasping its potential, I was like, “Whoa,” kind of head explode, like, “Damn, this thing’s gnarly.”

Let’s touch on the current status in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean right now?

JR: As of early December, we are around the 3,500 filter mark, which if you do the math, and I know this isn’t the case, but if you do the math on a filter being used at its capacity then you’re talking over 100,000 people would be benefiting from that amount of filters. I think it would be more like 300,000 but I don’t think every filter’s being used at its capacity, which is totally fine and normal. Let’s say you fall short of that and on an estimation of 10 to 15 people using a filter, which is very, very, very realistic, it’s probably higher than that, you’re looking at 40,000 or 50,000 people that have been touched and legitimately touched, benefiting from the work that we’ve done and that’s a huge impact in a short period of time.

Our goal right now with our current budget is 5,000 filters, which is a lot. That’s going to do a lot of good especially with the way that we implement those filters, they’re going to be used at a higher level. We’re looking at one filter helping 75 people, and they take great care of it and then we come back around four years later, and it’s still doing the same thing, I mean, that’s priceless.