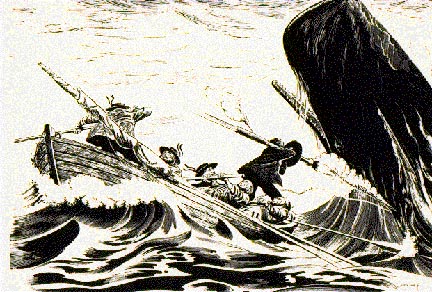

Imagine if this was your job: You set sail in a wooden ship powered only by the wind. In the middle of the ocean, a thousand miles from anywhere, you spot a whale. You scramble over the side of your ship into a 25-foot boat with five other men, and row as fast as you can towards one of the largest animals on earth, twice the size of your boat, or more. You then throw a harpoon into its back, and hold on for dear life as the whale thrashes, leaps, rolls and dives, doing its best to smash you and your boat to pieces.

If you survive that, and if your boat isn’t pulled so far away from your ship that you’re never seen again (yes, it happened) then you then have the joy of tying a dead whale to the side of your ship and working 8 to 24 hours without sleep stripping the blubber off the carcass while swarms of sharks are thrashing about below just waiting for you to fall overboard. Oh – and you won’t be going home for another two years.

For over 100 years, that’s what the men of Sag Harbor did to make their living. And they did it so well that the village became one of the largest whaling ports in the country.

The village was settled in about 1730 by residents of the surrounding towns, to take advantage of the deep, sheltered water – the best anchorage on eastern Long Island. Although the earliest voyages on record are from the 1760s, Sag Harbor whaling didn’t really get going full scale until after the American Revolution. In 1785 business partners Benjamin Huntting and Stephen Howell sent two ships down to the coast of Brazil that returned with about 350 barrels of oil each. It wasn’t much – just a few years later ships would be coming home with 2,000 or even 2,500 barrels – but it was enough. Sag Harbor was on her way.

For the next 50 years or so Sag Harbor enjoyed good times, or “greasy luck” as the whalemen would say. Whales were plentiful and there was no reason to even leave the Atlantic. Sperm whales and right whales were the usual prey. A typical voyage would last about 10 months, typically cruising on the whaling grounds off the coast of Brazil. To get there, a Sag Harbor whaler would follow the trade winds; first sailing east towards the Azores, then down the coast of Africa and finally back west to the whaling grounds off the coast of Brazil. In a ship powered only by the wind, this was actually a faster way to get to the whaling grounds than by sailing directly south.

After a few months of hunting she would head back home. Upon her return, the (hopefully) thousands of oil barrels were unloaded, and the ship would completely repaired and refitted by a swarm of village tradesman. Carpenters, caulkers, painters, boat builders, sailmakers, riggers, blacksmiths and coopers all worked as fast as they could – a ship in port was a ship not making money. Lastly, a new crew was found and the ship was off to sea again just a few weeks after her return, leaving tearful mothers, wives and families behind once more. While at first the ships were filled primarily with local men, eventually the fleet grew so big that it outgrew what manpower the local towns could provide. Men from all over world came to Sag Harbor to serve on board.

Eventually, the great success of the industry brought its own downfall. Too many ships were trying their luck, too many whales were being killed. By the 1840s, the industry began to change forever. With the Atlantic “fished out,” American whaleships were forced to go further afield in search of their prey. Sag Harbor whalers were no exception. Soon, the waters off Japan, Hawaii, New Zealand and even the Arctic Circle were as well known to them as Gardiner’s Bay.

On the surface of it, the voyages were just as successful; the ships would come home full. But now, instead of 10 months, voyages could last two, three or even four years. All that extra time at sea meant more money paid out for repairs, for supplies, for food; more “downtime” was spent just sailing to and from the Pacific. Profit margins began to shrink, and then disappear completely.

Furthermore, kerosene and petroleum began to take away the whale oil market. By the mid-1850s, it was clear the great days of whaling were a thing of the past. One by one, Sag Harbor’s whaleships were sold off. In 1845 her peak year, Sag Harbor had 64 vessels in her fleet; five years later, there were just 24.

Sag Harbor’s last whaler, the brig Myra, sailed in 1871. She would never return, being condemned in Barbados in 1874, too leaky and worn to safely make her way back home. With her demise, Sag Harbor’s whaling industry came to an end. Her wharves slowly went to rot. The boat shops and cooperages and oil yards closed. Her streets grew quiet, no longer teeming with hardy, boisterous sailors. It was, as one local resident wrote in 1872, “Dozeville.”

Her whaling industry was gone, but happily, her heritage was not forgotten. Much of it is now gathered in the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum and other local institutions; a fitting tribute to the industry that was the beating heart of the village and to the men who dared to call the sea their home, and dream of “greasy luck.”

Word + photos by Richard Doctorow of the Sag Harbor Whaling Museum. As featured in Whalebone’s eighth issue, the Water Issue.