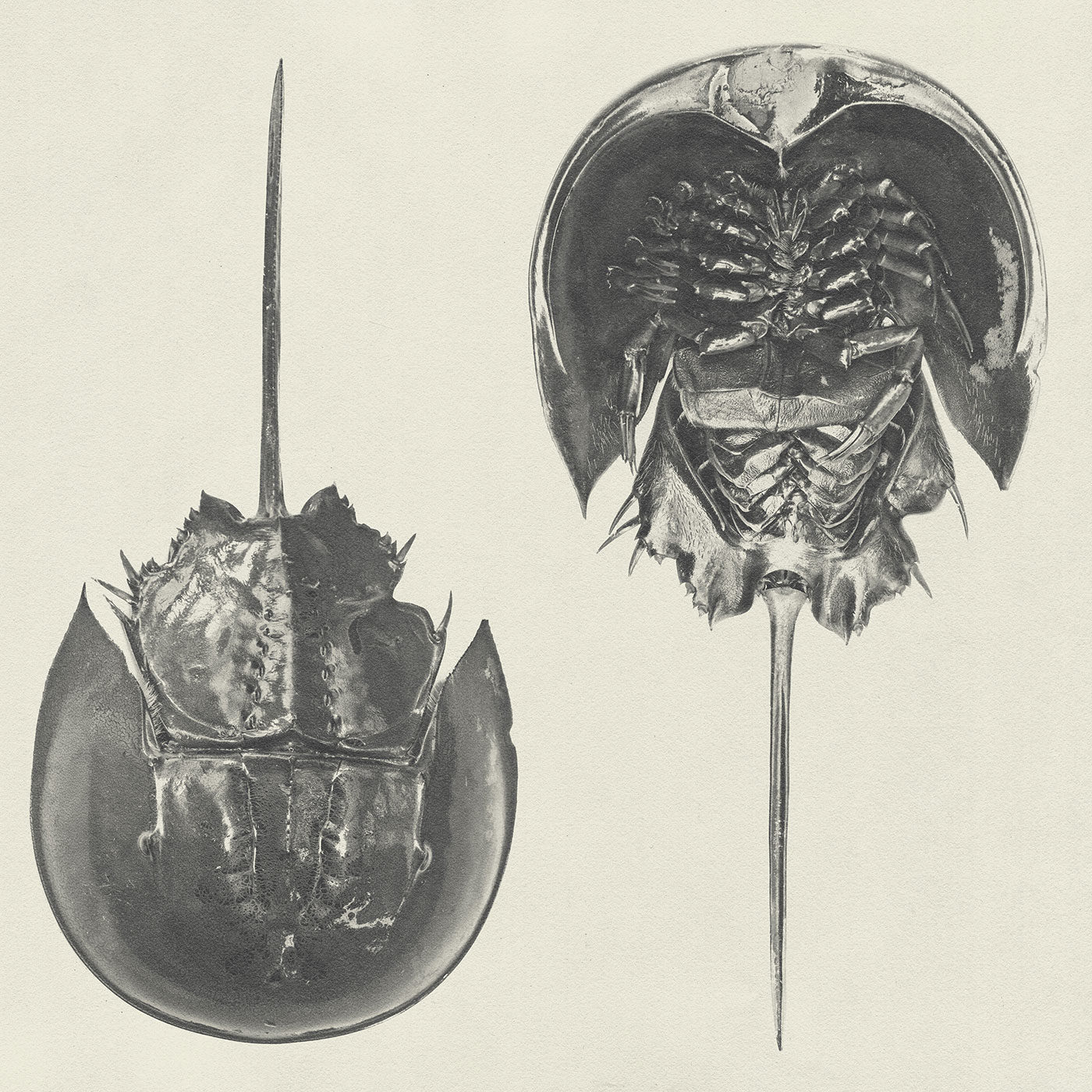

How horseshoe crabs held the key to vaccine testing in their 450-million-year-old cells

The horseshoe crab has been around for about 450 million years, walked with dinosaurs and survived five extinctions. As Dr. James Cooper, a pioneering pharmacologist who used Limulus polyphemus in his research thanks to distinctive qualities in its bright blue blood, told Whalebone, “That means that the horseshoe crab had to be evolutionarily very successful. It’s thriving under difficult circumstances.”

And that very peculiar blood that has evolved to help make Limulus polyphemus so durable has been crucial to some much more recent medical breakthroughs. Particularly when it comes to vaccine development. Dr. Cooper began his graduate research at Johns Hopkins in 1969 and, “One of the things we noticed there was we didn’t have a reasonable way to test for endotoxin, which is a very dangerous toxin from the cell wall of certain bacteria—the most prevalent one is the Gram-negative bacteria.” If endotoxins are present in something being injected into a person they can cause fever, infection, organ failure and death. Pretty damn important when you release a potentially life-saving vaccine to hundreds of millions of people to be sure it’s not going to kill them.

Up to that point, testing for endotoxins in vaccines meant keeping a colony of rabbits. Like really a lot of rabbits. Tens of thousands of rabbits. Which sounds pretty cute until you get to part about injecting them with potentially deadly bacteria and the tiny rectal thermometers the researchers used on them to gauge if endotoxins were giving them a fever. It also took a really long time for this vital part of vaccine testing.

Scroll over the droplets for a deeper dive into the anatomy of the horseshoe crab.

Turns out that one of the remarkable ways horseshoe crabs had evolved is that their blood clots if endotoxins are present. According to Dr. Cooper, “The horseshoe crab has developed proteins that protect it from microorganisms. To me, microorganisms are our most important predators. Think of the bubonic plague. Killed half of Europe. This is deadly stuff. They died of infections but they also died of the impact of endotoxins because even after the bacteria died, the endotoxin is still active.

“So yes, the horseshoe crab’s been around a long time. And it has been very successful in its evolutionary process. One of the most important reasons I believe for its long-term success is its ability to control microbial contaminants. It has a coagulation system that recognizes these bacteria that have endotoxins.”

This evolutionary oddity, so important to the horseshoe crab’s survival, was also key to speeding along vaccine testing (and sparing an awful lot of rabbits some uncomfortable fates). Fred Banks and Jack Levine at Hopkins had developed LAL (Limulus amebocyte lysate) with horseshoe crab blood as a test for endotoxemia in patients who had septic disease. That actually didn’t work out, but Dr. Cooper realized in an aha moment that all the elements for creating a very sensitive and reproducible test for endotoxins was inside the cells of the horseshoe crab. Getting there usually leaves the horseshoe crab relatively unscathed, with scientists catching and releasing them with a little blood donation in between.

The result is a simple test that can be done in a test tube that ensures safe vaccines quickly. The rabbits are probably pretty happy about it, too.