Finding the top of the Cretaceous food chain where you least expect it

Words by Liz Tascio | Illustrations by Zack Causey

Not so very long ago, relatively speaking, Lewis and Clark found the bones of a sea monster. Where you might expect Lewis and Clark to be but definitely not where you would expect to run across a deep-sea denizen.

They made their discovery in 1804 in a hillside in the Midwest of the United States more than 1,000 miles away from any ocean. What they found was forty-five feet long and startling. The fellas collected some bones, sent them back east for study, and continued on their way.

Scientists have been collecting evidence of an ocean—shells, teeth, pearls, bones—in the Midwest for just a few hundred years, which is really a breath, just barely a breath, in the span of time during which there has been life on Earth.

The open, airy Midwestern body of the United States is the descendant of a long, shallow, inland sea that’s been gone for more than 60 million years. The landscape rolls now with highways and hills and grass, with glimmering wheat fields and the green and yellow fronds of corn and the reddish-brown of milo, with islands of suburbs and cities. Tall, eerie geographic formations like Monument Rocks in Kansas remind us that the land here was shaped by deep, long-vanished water, that the limestone rock itself is made of the calcium carbonate of crushed marine animals and seashells.

The teeth and vertebrae of sea monsters that continue to surface, especially in the chalky hills of western Kansas — one of the richest deposits of marine fossils in North America — offer us a way to rethink time, and our place in it. The age of explorers venturing across a continent is but a blink when we reimagine time on the geologic scale of oceans.

The sea that covered the Midwest formed when the Earth’s plates moved and pushed the Rocky Mountains up, and the force of that pushed the middle of the continent down, flooding it from the north and the south.

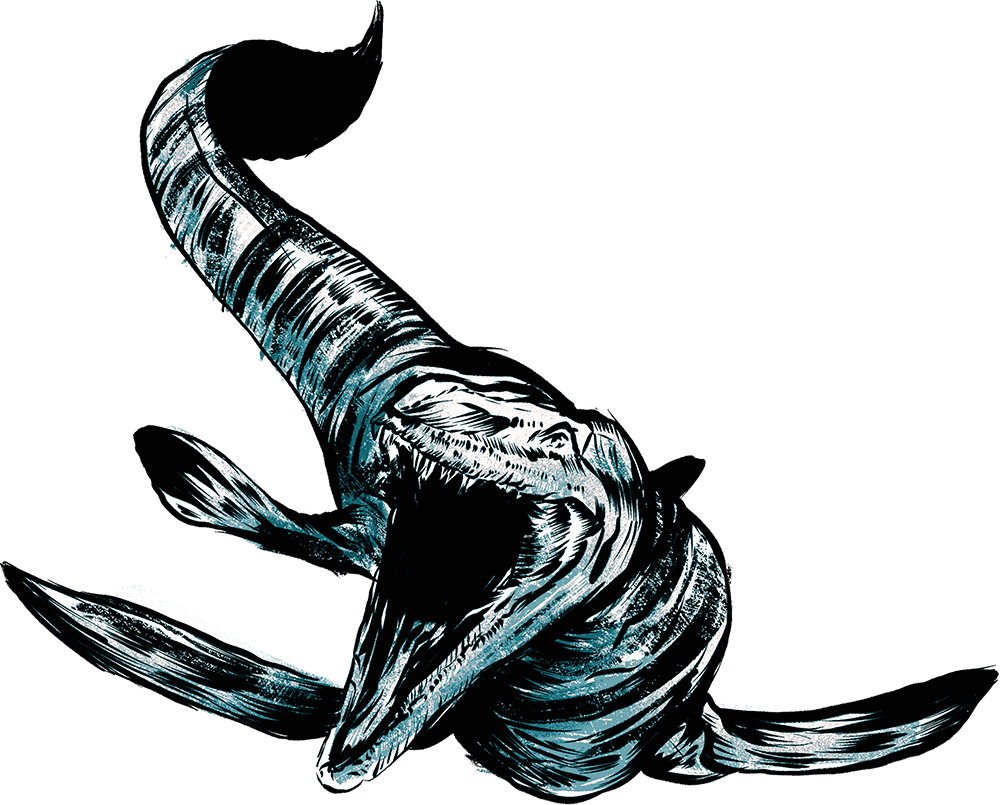

The sea creatures here had one king: the mosasaur, a massive, snake-like marine lizard the size of a bus. The mosasaur was so big and fearsome that it could kill and eat anything else in the water. And because most of the planet by far was covered in water, most of the planet belonged to the mosasaur.

The King

Mosasaurus, Tylosaurus proriger

The pride and joy of Kansas. Tylosaurus is the state’s official marine fossil. In its day it was one of the largest mosasaurs ever. A Tylosaurus discovered in Kansas in the 1800s had a five-foot skull and what may have been a 50-foot body. Unlike other mosasaurs, it had no teeth in the very front of its long mouth. Scientists think it used its head like a battering ram.

The mosasaur breathed air, like a whale, and its wide tail moved it sinuously, like a snake or a crocodile. It likely gave birth to live babies in the water, like a shark. It was voracious and ferocious, with a second row of teeth behind the first. Mosasaur species could be small, only about three feet long, but most were huge, 30 or 40 or 50 feet in length. Next time you’re driving through the middle of the continent on I-70, take a good look at a semi-trailer and think about a mosasaur being the length of that, swimming alongside you.

The mosasaur lived at the same time as the last dinosaurs, dying out with them during the fifth mass extinction. It lived on a planet we would not recognize, one with no ice at the poles, and with a vast and ancient sea where today there is none.

Time, as they say, passes.

The gift shop at the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays, Kansas, sells a cheerful T-shirt that reads, “Long time, no sea.” In the lobby of the museum, a replica of a mosasaur hangs from the ceiling, its green body and long, open jaw ready to greet visitors as they walk in the front door.

The exhibits include the bones of marine animals collected in Kansas: a 30-foot mosasaur species named Tylosaurus proriger; the giant sea turtle Protostega gigas; and the shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli, nicknamed the “Ginsu” for its knife-like teeth.

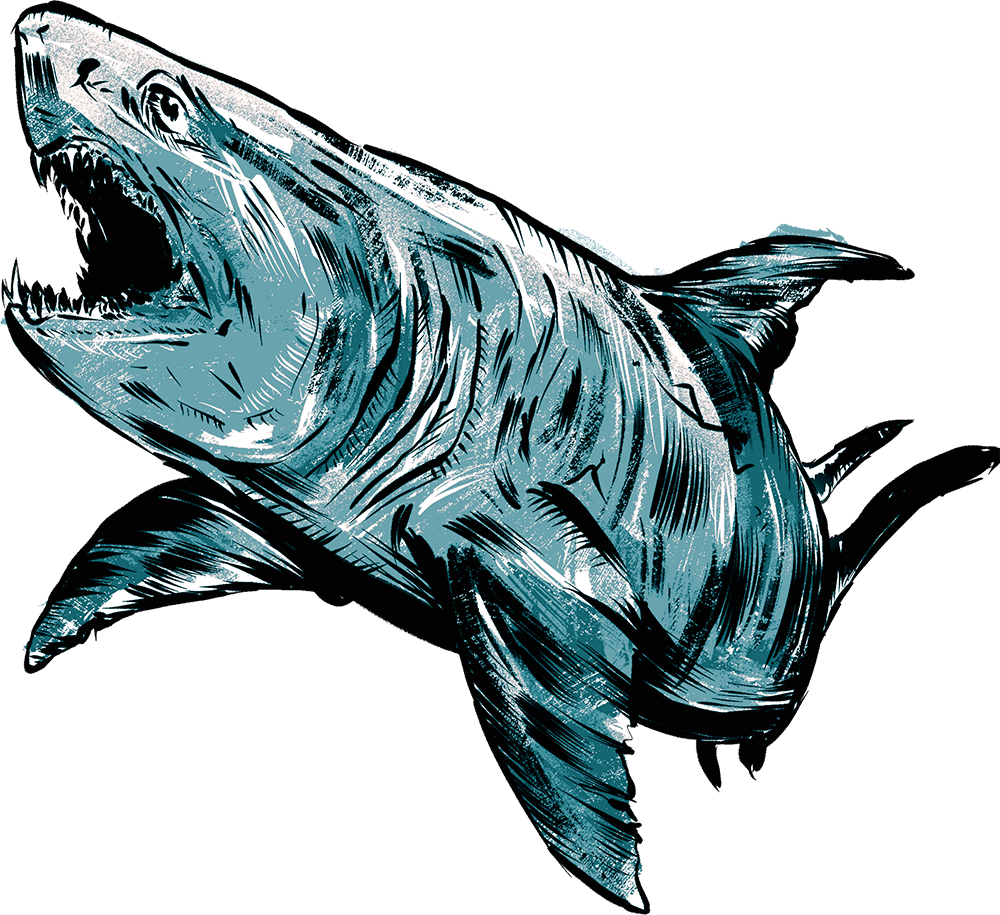

The Ginsu Shark

Cretoxyrhina mantelli

Earned its nickname with a mouth full of knife-like teeth. Sharks are mostly cartilage, which doesn’t fossilize well. But those long teeth survive. The Ginsu was about the length of today’s Great White, with an absolutely crushing bite. If anything was going to give the mosasaur some trouble, it was this shark. Paleontologists have found mosasaur bones with Ginsu shark teeth broken off in them.

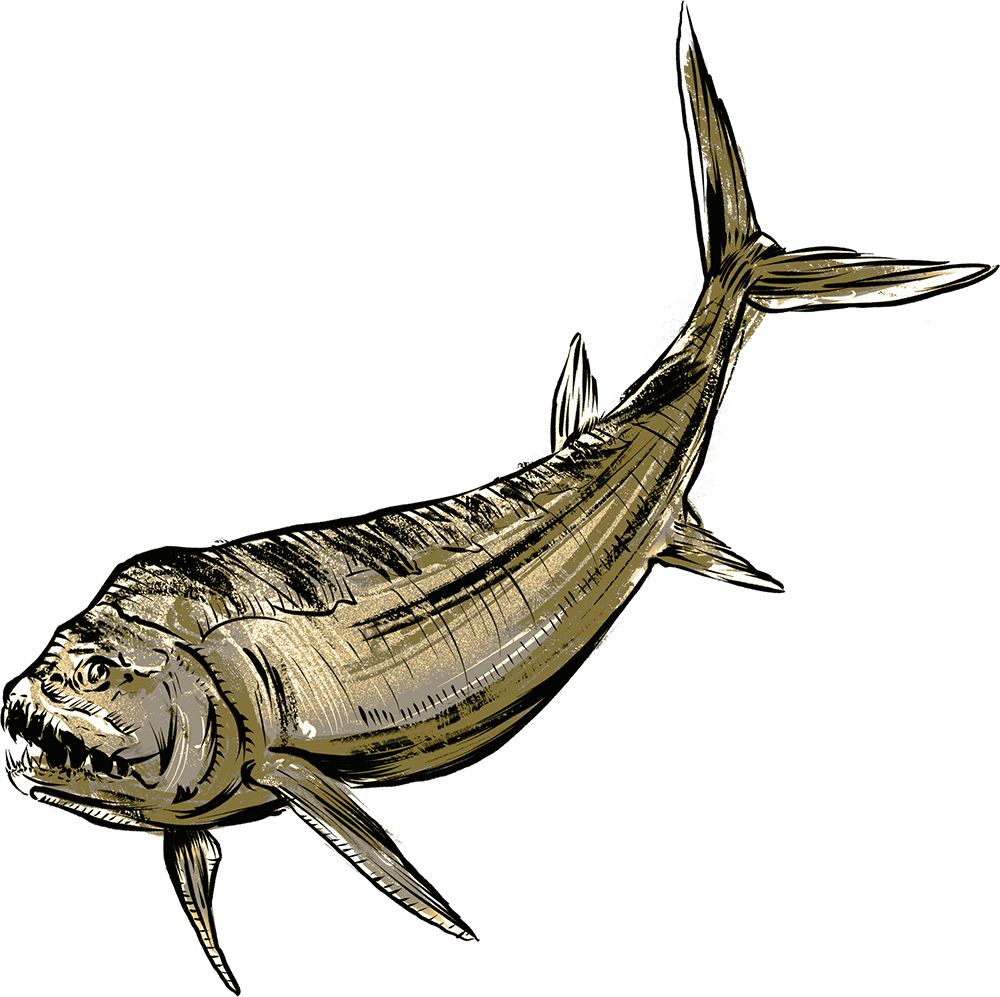

One of the most famous here is the “fish within a fish,” a 13-foot toothy Xiphactinus with an almost perfect six-foot-long Gillicus arcuatas in its belly. The struggles of the fish being eaten may have killed the fierce fish eating it, so they both died together and were fossilized. It is breathtaking, like witnessing a long-ago moment of deep time.

In the main exhibit hall, visitors can watch through windows as grad students work with fossils in a prep lab. And this is where shivers might go up your spine. If you are so lucky as to walk into the prep lab, you might suddenly be sharing space and air with millions-of-years-old bones lying on tables, left there mid-inspection.

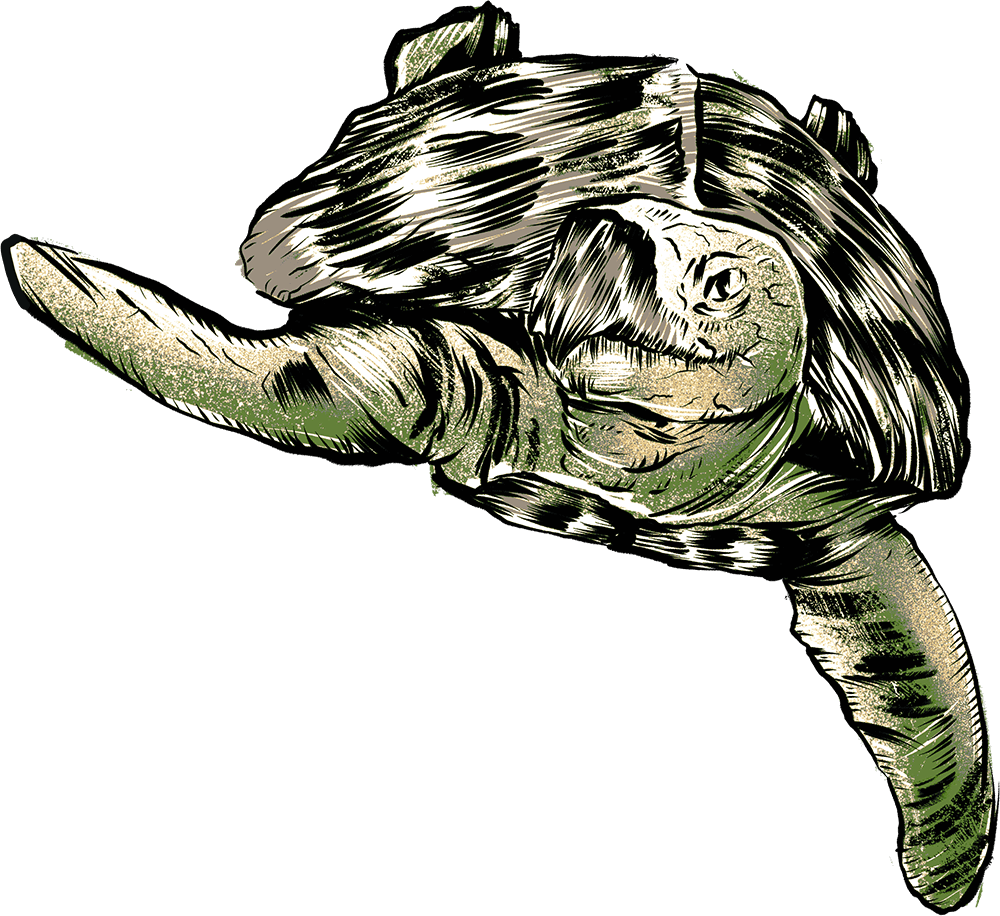

Giant Leatherback

Protostega gigas

The second-largest sea turtle to ever live, it could grow to about nine feet in length. Its shell was more like a leatherback than a hard shell. Modern turtles are smaller, but in general, turtle design has stayed the same for millions of years, outlasting species after species that tumbled into extinction. If it ain’t broke …

You would see the paddle of a sea turtle; the flat, toothy skull of a mosasaur; a large hunk of plaster on the floor with a big fish inside it, and a scrap of notepaper on top that reads, “Pachyrhizodus.” You might start thinking about the billions of years that life has blossomed and died out, and you might suddenly remember that humans are such a very small part of that history of life. You might realize you are looking backward through time at sea creatures that had no way of knowing their time was ending or that yours would someday begin.

When Dr. Laura Wilson was a kid, she collected shark teeth that washed up along Florida’s Atlantic coastline. Today, she’s a curator at the Sternberg and an associate professor and researcher at Fort Hays State University, specializing in paleoecology. Sure, she still likes to find shark teeth, but now she picks them up on dry land, and they’re millions of years old.

What the museum tries to illustrate, she says, is the concept of change through time. The museum displays one of its mosasaurs near an aquarium containing two live monitor lizards, and the notes on the exhibit make the evolutionary connection explicit: an invitation to look into the past and draw a line to the present.

Wilson says she used to get less worked up over the idea that eventually humans will become extinct, too—possibly because of how swiftly and dramatically we have altered the planet and its ecosystems—and that the world would reset and go on without us. Then she became a mom, and now in addition to thinking in terms of deep time, she thinks in generations.

“My own vision of my mortality changed when I had a kid,” she said. “There is a bit more investment in terms of the footprint we’re leaving behind, and what the world is going to look like in 40, 50 years when I’m not here, but my kid is, and maybe his kids are.”

Paleontologists examine fossils to try to understand history, prehistory, life on earth and its possible futures. Wilson studies Hesperornis, a flightless sharp-toothed sea bird as tall as a human, to try to understand changes in ocean ecology over time.

Bulldog Fish

Xiphactinus

The teeth on this very large, very bony fish have been described as fangs, or like a fistful of pencils. It was a fierce hunter. Nicknamed “the Bulldog Fish,” it probably grew to about 20 feet long. The inland sea of North America was full of them. The most famous Xiphactinus was found in Kansas with a 6-foot Gillicus arcuatas in its belly—it really did finally bite off more than it could chew.

Understanding the past gives science a predictive power, she says. We can model future ocean temperatures and salinity; we can predict how coastlines might change.

But we can’t really look ahead millions of years and know, the way we can look back.

The sea monster Lewis and Clark found, probably in what is now South Dakota, was most likely a mosasaur. The bones they collected were lost.

Sea creatures lived and fought and died in a sea in the middle of our continent. Their time is over, their ocean is gone, except for shadows that we find; it has been over for tens of millions of years. Will anyone find shadows of us, millions of years from now? Could a sixth mass extinction mean the remaking of the world for a seventh time, with new oceans, new coasts, new life? Will future species find fossils of us and be amazed at our bone fragments remade into rock; will anyone imagine our lives, our landscape, our oceans?

If we can reach forward now, into a future we will never see, and imagine all that—and then bring our minds back to today, perhaps we can better understand our own time in the sun.

How to Find a Sea Monster in Kansas

“You kind of just walk around looking at your feet,” says Richard Carr, a first-year paleontology grad student at Fort Hays State University in Kansas.

It takes practice to recognize what you’re seeing, though. Color isn’t reliable, because it can change depending on the environment. “Typically speaking, it’s kind of a textural thing,” Carr says. Teeth will often be shiny, and a rock with an organic shape may turn out to be bone. If you see a break or a fracture, check to see if the inside looks spongy.

As an undergrad in Montana, Carr and a group of fellow students drove out to look for fossils in the Bearpaw Formation, famous for marine and dinosaur remains. They split up to search, and Carr was looking at ammonites when he heard excited voices over the walkie-talkies.

“All of a sudden one of our colleagues started finding vertebrae,” he said. “So we run over there and start digging and we realize there’s more and more in the hillside. It went from a couple of bones to a complete skull and a couple of ribs.”

They had found a mosasaur. The group worked for hours, pouring plaster around the remains—called a jacket—and prying it out of the ground. The largest chunk of plaster and bone weighed 800 lbs. The smaller pieces they wrapped in tin foil and plastic baggies.

“There’s a lot of focus on dinosaur paleontology in North America, which is great,” Carr said. “But there is actually an even better fossil record from marine life in North America. I’m willing to bet that there are more discoveries to be made in marine deposits—fish, reptiles, birds—that have yet to be found.”