Tracing the history of precipitation prognostication from that time the first weatherman grunted “rock is wet” to literal rocket science.

Illustrations by Rae Keller

In The Beginning

“Rock is wet.”

650 B.C.

Up until ancient Mesopotamia, weather prediction was mainly left up to “omens,” but the Babylonians began to look to the clouds to help predict, based on their types and shapes, what soon might be falling from them. They do still often expect that to be frogs, however.

340 B.C.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle writes Meteorologica, a philosophical treatise (obviously) that dealt with phenomena occurring between the center of the Earth and the sky, including how rain falls, clouds form, and cataloging wind, thunder and the like. Remarkably accurate for the time. Despite a whole lot of it being wrong, held as the standard for about 2000 years, into the 17th Century. Oops.

300 B.C.

Chinese astronomers develop a lunisolar calendar that basically divides

the year into 24 seasons based on what type of weather would come, each having a festival associated with it. Those ancient Chinese astronomers liked to party.

1592

Galileo Galilei invents the thermometer. Instead of just shouting, “fa caldissimo!” while sweating, Italians could now attach a number to their complaint.

1643

Evangelista Torricelli invents the barometer to measure atmospheric pressure. His work in geometry also leads to the creation of calculus, so fuck that guy.

1752

Ben Franklin, who Bostonians probably had gotten used to seeing chasing thunderstorms on horseback while carrying large metal rods and could be called the first storm chaser in addition to founding father, flies a kite carrying a metal key into a storm to prove that lightning is electricity. The lightning rods he goes on to create protect buildings in the colonies from lightning strikes.

1803

Londoner Luke Howard publishes “Essay on the Modification of Clouds,” which sought to create a cloud classification system. He went on to name them. All of them. Here’s looking at you “cirrus” and “cumulonimbus.”

1860s

With the invention of the telegraph, early meteorologists begin to share the

data they are recording in disparate locations, some patterns emerge and the first weather maps are drawn. You just know somebody pecked out a fake heat spike that would make somebody else thousands of miles away draw a dick on a map.

1920s

Radiosondes, small radio transmitter boxes light enough to be carried into the sky by a balloon with basic weather instruments (measuring temperature, moisture and pressure) onboard, are invented.

1946

The effort to not just predict the weather but control it begins to gain traction. Pilot Curtis Talbot, flying for the General Electric Research Laboratory, releases three pounds of dry ice into the clouds creating the world’s first manmade snowstorm.

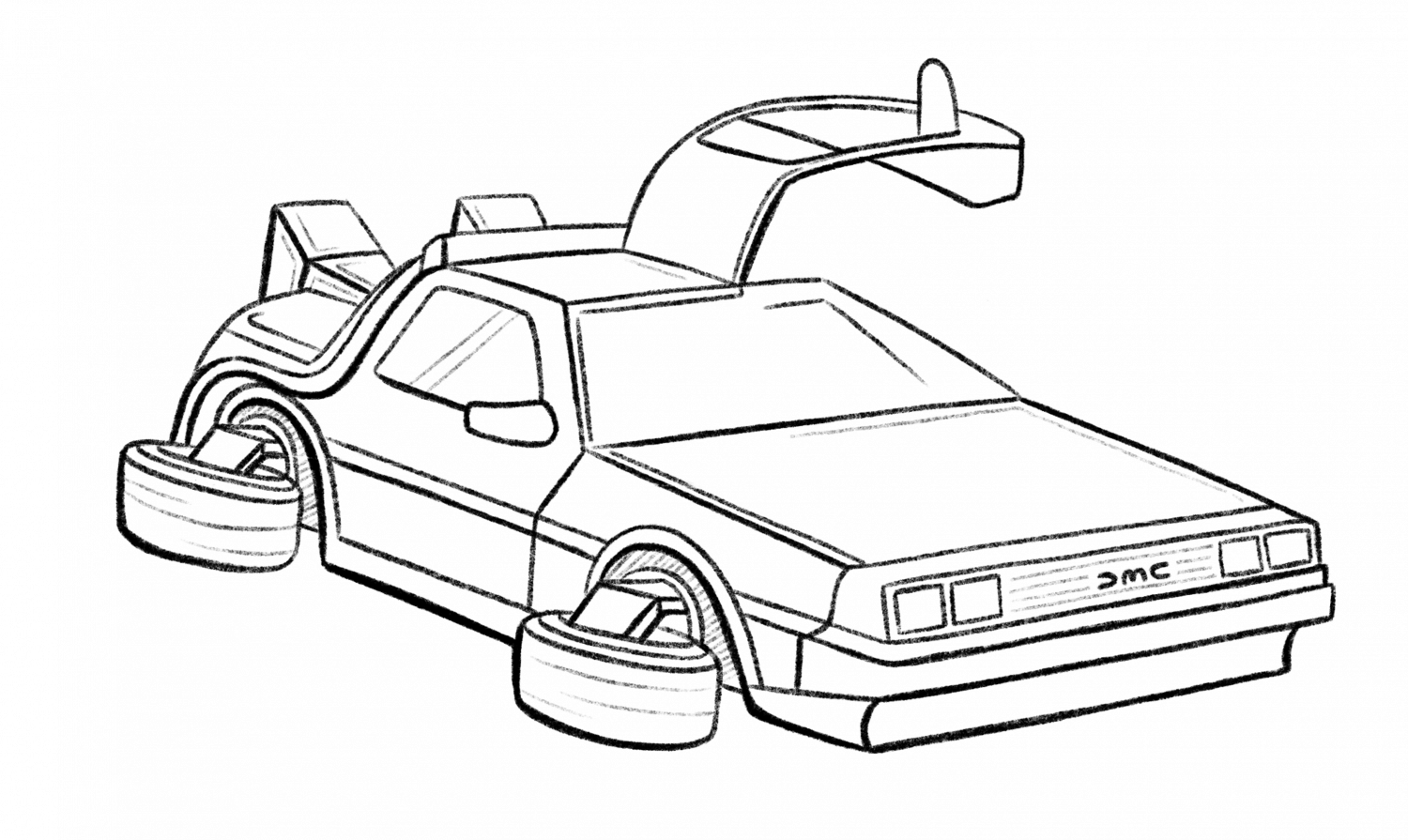

1955

Dr. Emmett Brown harnesses 1.21 jigowatts of a lightning strike, channeling it directly into a flux capacitor to power a time travel vehicle (which explains how he predicted the lightning strike). Maybe this one should be in 1985.

1959

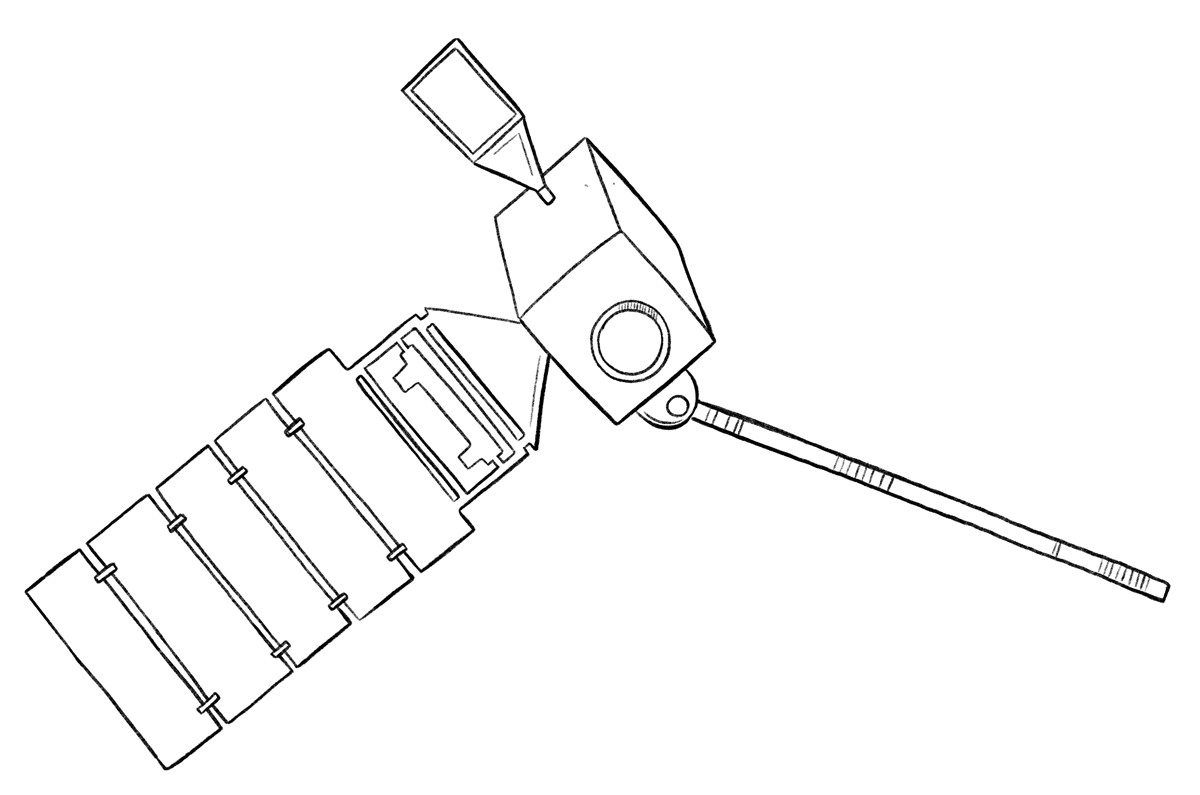

Setting the tone for the early space race, the Soviet Union launched Vanguard 1, the first weather satellite, though the Sputnik look-alike did not function as intended. Or at all really.

1960

In April, the US launched TIROS (Television InfraRed Observational Satellite), designed by the RCA Corp. and considered the first successful weather satellite. Many more pieces of metal are then hurled into space thereafter.

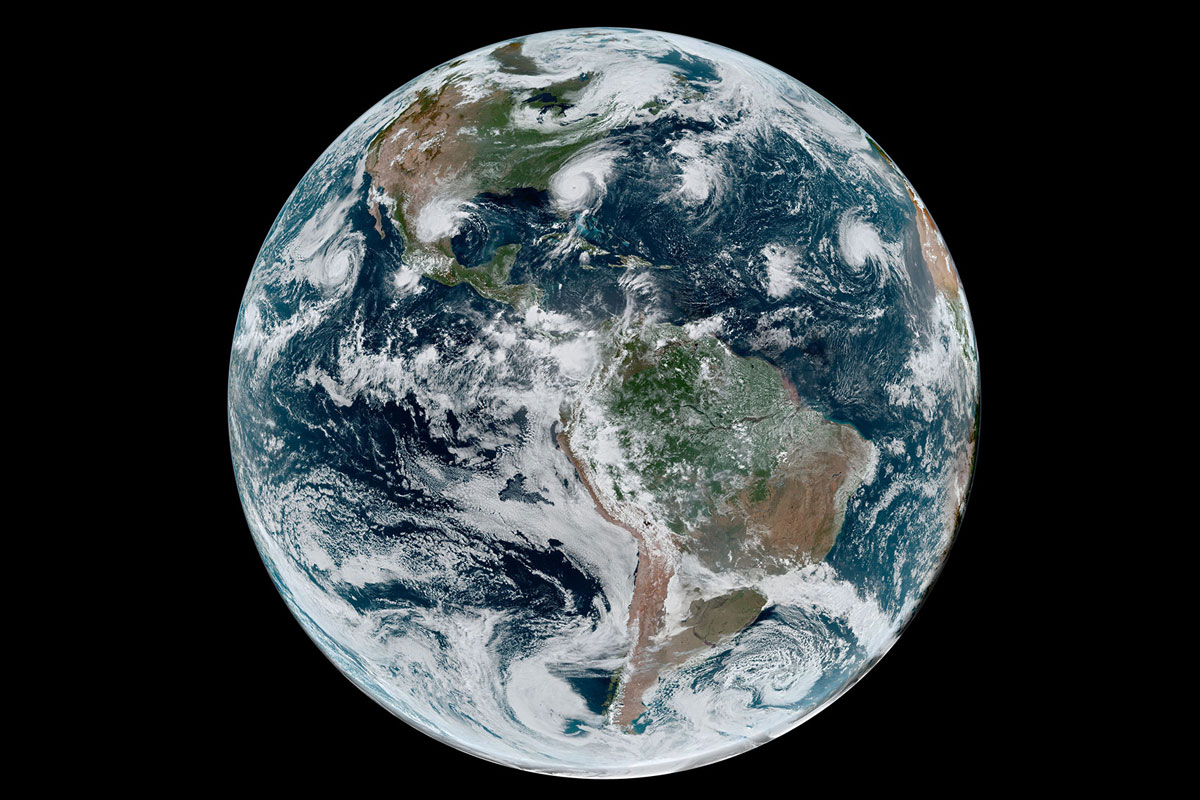

1970s

Nimbus series of satellite systems are launched by NASA—including the first Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES) in 1975—revolutionizing weather forecasting with consistent global measurements and imagery. With the first ground-to-satellite communication system, it also established the modern GPS era, so you can thank Nimbus for not missing your exit.

Today

With ever-more advanced spacecraft and measurement technology onboard, the fourth generation of the GOES Satellite Network keeps a birds-eye view on weather systems around the globe and beams down nearly real-time imagery—the Nimbus satellite images were like a flipbook compared to GOES-R–U which is like that part in the movie where Tom Cruise says, “Enhance,” and the numbers on a licence plate become visible from space except for clouds—that many of us can now access from the phones in our pockets, screenshot and post to IG with the caption “LOLZ #thatlookslikeadick.”