Step out to the light from the darkness of your local movie theater this summer and it may seem that any film these days can fetch hundreds of millions — even a billion — in ticket sales. But it wasn’t always that way. Before CGI painted our movie screens, before the dawn of superheroes and the awakening of franchises from galaxies far away, there was a time when summer was considered an off-season for moviegoers. (Who would want to sit in an non air-conditioned theater in the middle of July?) In fact, 40 years ago, it took a dramatic series of missteps and accidents to launch the age of the summer blockbuster — an age spawned of all things by a malfunctioning robotic shark.

Copyright by Universal Studios and other respective production studios and distributors.

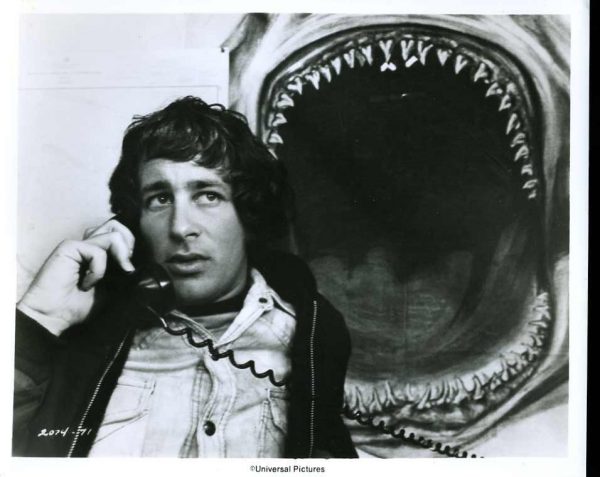

Imagine what Steven Spielberg must have felt when it came time to start shooting Jaws. When the 27-year-old director rolled up to the set, he had only one film on his resume: Sugarland Express, a flop about a Texas couple on the run from the police. Critic Roger Ebert famously skewered the young movie maker, saying Spielberg “paid too much attention to all those police cars (and all the crashes they get into), and not enough to the personality of his characters.” Looking out at Martha’s Vineyard in the summer of 1974, Spielberg was determined to redeem himself.

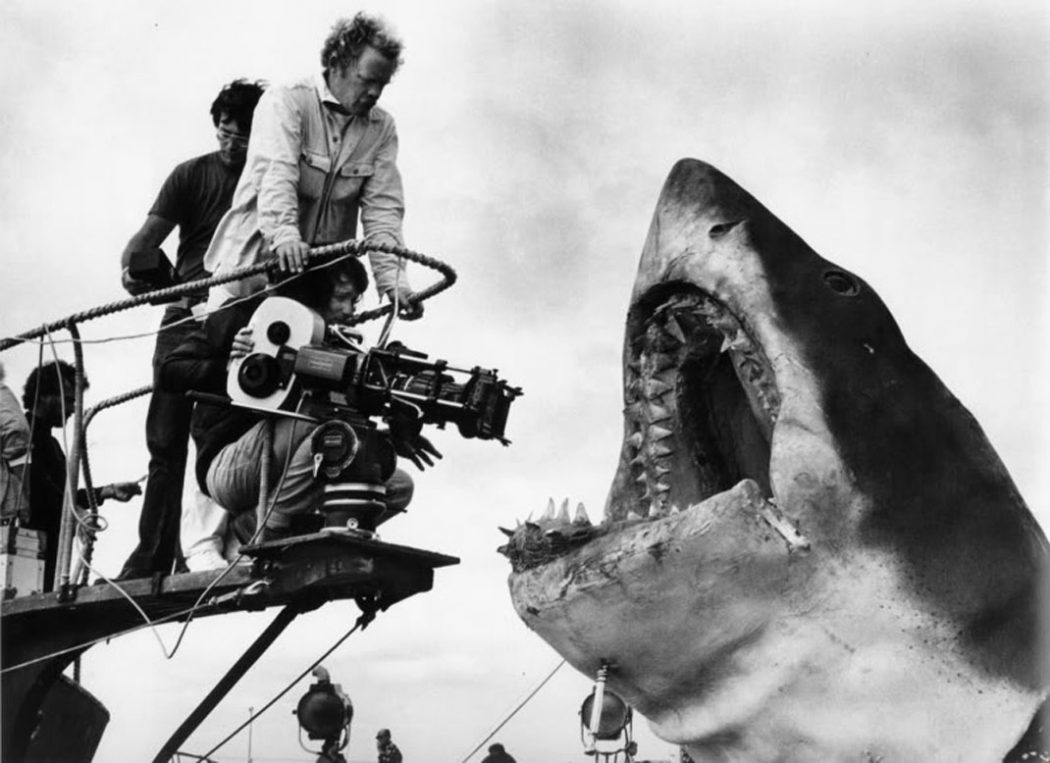

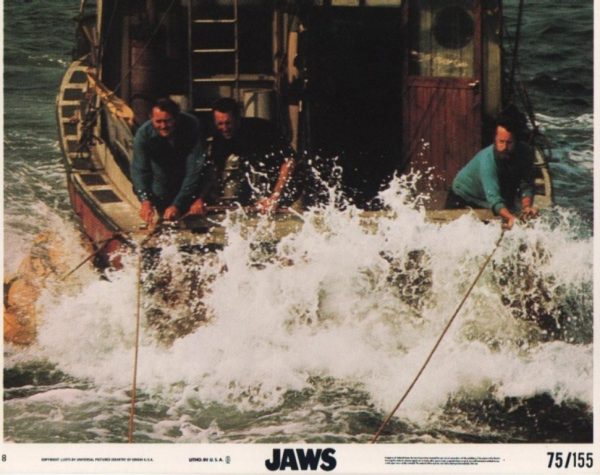

First and foremost: realism. To capture the terror of a great white shark attack, Spielberg believed the traditional Hollywood approach — shooting on a soundstage in a giant tank of water with a projected background — just wouldn’t do. Sure, it was dependable, but it was sterile and fooled nobody. Jaws would be different: They were going to shoot it on the open sea. Although author Peter Benchley set the novel on the fictional Long Island resort of Amity Island, Spielberg opted for Martha’s Vineyard. With its twelve miles of shallow water, there were ample places to shoot the mechanical sharks, and the stretches of waist-deep water created an atmosphere where virtually no one was safe.

Copyright by Universal Studios and other respective production studios and distributors.

There’s a reason why Hollywood avoided the open seas and pretty soon everyone realized why. The mechanical sharks shorted out, halting production. Nicknamed “Bruce” after Spielberg’s lawyer, the machines relied on a complicated series of pneumatic pumps that got fried by the sea water. Breakdowns happened daily. Boats sank. Members of the cast and crew nearly drowned.

Spielberg made the most of the delays: They gave him time to work on the script. Eager to capitalize on the success of Benchley’ novel, Universal Studios had cameras rolling before the script was even finished. So while equipment was being repaired and crew members fished from the ocean, Spielberg was busy with rewrites. He nixed the part where Hooper (Richar Dreyfus) sleeps with the wife of Police Chief Brody (Roy Scheider). He also sprinkled bits of humor throughout the script in order to make the characters more likable. Spielberg had the actors improvise their scenes while he wrote scribbled down the dialogue. The impromptu workshops proved a success, resulting in bigger-than-life characters that enraptured audiences — all thanks to faulty props. (Scheider famously ad libbed the line: “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”)

Copyright by Universal Studios and other respective production studios and distributors.

Realism alone wasn’t enough. Spielberg learned that lesson from Sugarland Express. He knew he needed compelling characters to make a hit. From the start, however, casting proved a challenge when box office stars like Robert Duvall, Lee Marvin, and Jon Voight passed on roles. Even Robert Shaw and Richard Dreyfuss initially snubbed Spielberg. Fortunately, Shaw’s wife and secretary persuaded him to take the part; while Dreyfus found himself crawling back to Spielberg after starring in a dud early that spring.

Signing on the menacing Shaw and the brash, young Dreyfus seemed like a coup at first, but the two frequently fought off-camera. (Some believe that Shaw was annoyed by the endless stream of local girls in and out of Dreyfuss’ trailer.) “[Robert Shaw] was a perfect gentleman whenever he was sober,” Richard Dreyfuss said in an interview. “All he needed was one drink and then he turned into a competitive son-of-a-b****.”

Copyright by Universal Studios and other respective production studios and distributors.

Legend has it that Shaw would often try to distract Dreyfuss before the cameras began rolling. He had also once offered Dreyfuss money to climb to the top of the mast on the Orca and jump in the water. According to Roy Scheider, it was Dreyfuss’ youth that irked the veteran Shaw, “He would say, ‘Look at you, Dreyfuss. You eat and you drink and you’re fat and you’re sloppy. At your age, it’s criminal. Why, you shouldn’t even do ten good push ups.”

Although he caused his share of problems behind the scenes, Shaw’s performance delivering the Indianapolis speech remains, for many, a masterclass in acting. But like the rest of the production, it didn’t go as smoothly as it appeared. The initial monologue was eight pages long which Shaw, an accomplished writer himself, pared down to four pages. When he stumbled onto the set to shoot it, however, he was so drunk that Spielberg gave up shooting the scene. The director tried again the next day — this time with a sober performance from Shaw. (The final cut uses footage from both days, although Shaw’s delivery is no less convincing.)

Copyright by Universal Studios and other respective production studios and distributors.

Throughout production, Spielberg spent sleepless nights in his log cabin stressing about rumors that he was going to be pulled from the project and would never find work again. He brought a pillow from home and kept a stalk of celery beneath it because the smell comforted him.

Shooting mercifully ended in October 1974. Production had taken three times longer than what was planned and they were millions of dollars over budget. After months of equipment failures, lighting storms, and infighting among the cast and crew, Spielberg was so afraid of a violent mutiny that he flew home before the last scene was filmed.

But as the young director sat through the first test screening, there was no doubt that they had snagged a big one. Audience members reeled in horror. One viewer became physically sick. Soon, the film had sold more tickets than any other before it and would eventually pull in $430 million worldwide. Despite what seemed like certain disaster, Spielberg and his team turned disaster into success and had managed to create the world’s first summer blockbuster.

Words by Bruce Myint, as featured in Whalebone’s seventh issue, the Throwback Issue. Look out for our upcoming issue, the Water Issue, hitting shallow watered-beaches all around America July 1st.