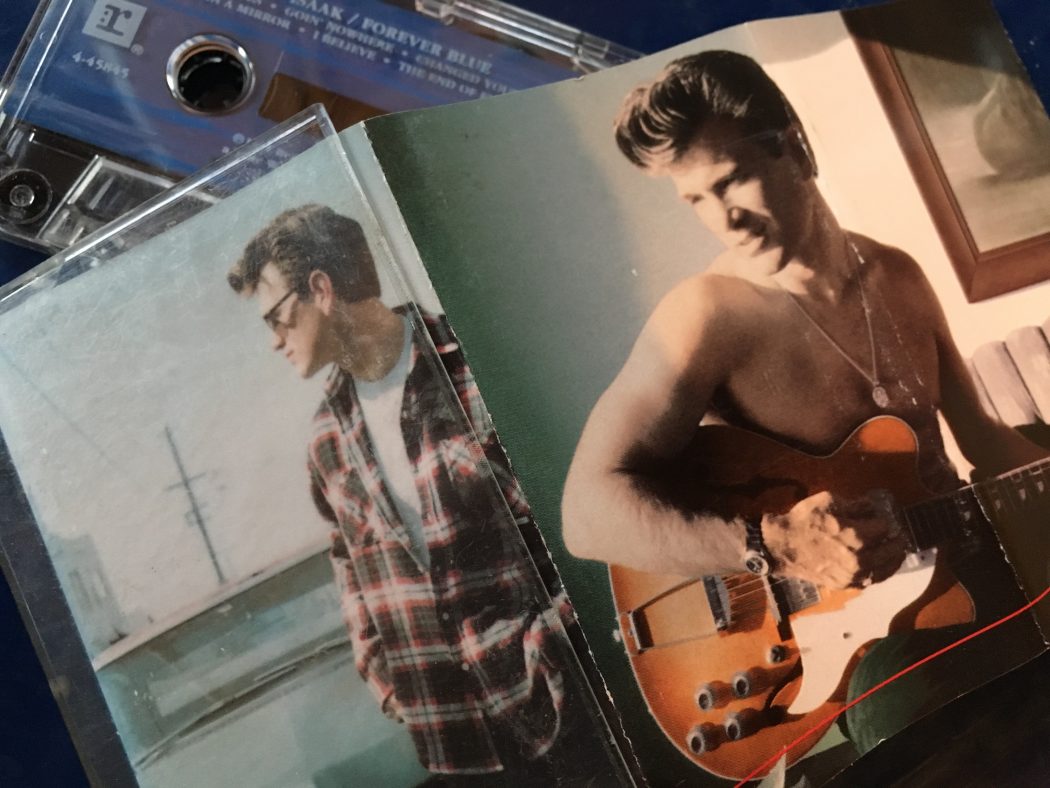

Nothing lasts forever—even Forever Blue. I’m talking, of course, about the 1995 Chris Isaak monograph of melodramatic melancholia. When I say nothing lasts, I don’t mean the songs or the album as a whole, which in fact holds up surprisingly well, but of the physical media itself. My cassette copy is on its way out. And just when I’d come to appreciate the album anew.

I hadn’t listened to the album—or even thought about Isaak, for that matter—in years. But chance and circumstance had brought us together. And now time is tearing us apart. Just as it would all happen in one of Mr. Isaak’s sentimental brokenhearted ballads.

Chance and circumstance brought us together. And now time is tearing us apart.

For years, my Jeep had nothing fancier than AM and FM on its dial. When the signal started to fade, I upgraded to a-still-circa-late-’90s model, but one that had a cassette deck. The AM/FM came in clear as a bell, but I lacked any cassettes. Since they’d gone out of stock long before Sam Goody and Tower closed their doors, they weren’t plentiful either.

Digging through the back room of Angel City Books & Records in Ocean Park I found the used copy of Forever Blue in the bottom of a dusty cardboard box. It’s the one with that song from Eyes Wide Shut, but not the one with that song where he makes out with the naked model on the beach in the video. I shrugged and figured, what the hell. I always liked Isaak. Rocco, the owner of Angel City Books, charged me a buck and said, enjoy it.

Since it was the only cassette I had, it enjoyed permanent rotation in the in-dash for about three months (until I found a duped DMX at Artists and Fleas). I drove each day up the coast from Santa Monica to my office in Malibu. That’s a lot of Forever Blue.

But it turns out, it’s not too much Forever Blue.

The album began to fade into the background a little bit. It was always there, but it felt solid, reliable, dependable. The aching and sadness were comforting. The album exists almost in a dream state. One where maybe Morrissey fronts a mariachi band playing soft surf rock.

It sways and shimmies in a way and is consistent throughout (save for the odd Thorogood growl of “Baby Did a Bad, Bad Thing”). It’s almost a concept album on a sunny kind of sadness. Even the dirges on the album have a skiffling little wood block beat. And as the constant soundtrack for driving up the PCH in a ragtop Jeep with the fog rolling off the ocean to your left in the morning and then sinking into it to the right in the evening, well, let’s just say, it suits the mood.

Months went by. The lyrics burned into my consciousness. I memorized the location of every riff, flourish, yodel and whine. When these things began to fade, it was at first startling.

Tapes don’t wear in the charming way that vinyl does, bathing you in warm pops and hiss. Every time the wheels of the cassette spin and pull the physical strip of tape over the metal tape head, a little of the material wears off. Sometimes it stretches and pulls. Chris’s words began to warp with exaggerated wow and flutter. Sound began to fade in and out. At some points, the wrong side picks up and in mid-song Chris will be singing backwards from the other side of the tape like he’s trapped in Twin Peaks.

At this point, the tape is nearly unlistenable. But I still try to reconnect with the old magic. But now when Isaak croons on the pedal-steel-inflected The End of Everything, “This is the end of happiness. This is the end of dreams,” he warbles a bit and then the cassette stops in mid-“This is the end I know.”

We both know it.