Comedian Mark Normand Goes Back Stage with Colin Quinn

@marknormand x @colinquinnshow

When you ask comedians who’s the most New York stand-up, Colin Quinn’s name comes up first—he’s actually probably the most Brooklyn comic, too. He’s sometimes called the comic’s comic, and comedian Mark Normand chose him to interview for The Interview Issue. Don’t be surprised if they talk about comedy. In Quinn’s latest comedy special, “Colin Quinn & Friends: A Parking Lot Comedy Show” on HBO—an attempt to stage a COVID-era live show—bombing is part of the point. And so is showing the comedians as themselves in the long moments right before and after they go onstage. Much like these moments before the interview.

Listen to the whole conversation

Before the interview starts…

Publicist, Pam: You guys are buddies. So you should riff on whatever. You know what I mean? It’s going to flow. Like you’ll ask a question, then you’ll get into something. Don’t worry about it. I mean obviously, touch on the special and the book.

Mark: I know, but I didn’t want to ask him the same 17 questions that every Tom, Dick and Harry is asking.

Pam: I know, but it’s not going to go that way because he’s not friends with every Tom, Dick, and Harry.

Mark: Got it, okay. So we can riff. I didn’t know if I had to keep it in line.

Pam: No, no, no, riff. Where is he? Oh. You know what? Hold on. I think he’s expecting me to connect it, hold on. [long pause] All right, Colin’s on.

Mark: Hey, hey.

Colin: Hey. What I want you to do is hit the Cellar. It would have been much easier.

Mark: Way easier. I agree. I’m down. I live on Minetta.

Colin: Let’s do it.

Mark: Yeah, we got to do it soon, because I’m going down to New Orleans to kill my family for Thanksgiving.

Colin: You’re going to New Orleans. New Orleans is not my favorite city by a long shot, but I do love Confederacy [of Dunces] more than anything. Anything in comedy on the planet, Confederacy is… there’s nothing close to it.

Mark: I agree. It’s one of the funniest books, and I hope they don’t make it into a movie like they keep threatening us with.

Colin: No, no, they’re not going to do it.

Mark: It’ll never hold up. It’ll never be the same, and the movie’s going to tank, and everybody’s going to hate it.

Colin: Yeah, they will. They’ll never do it.

Mark: I’m sorry, you gotta, you probably do 16 of these a day, I imagine, with all the press on the special and the book. So thanks for doing this one.

Colin: Sure.

Mark: You probably got to do another Chris Millhouse podcast. I don’t want to keep you.

Colin: Yes, I do. I have three more today.

Mark: Oh, jeez. That’s brutal. At least the podcast is great because you feel like you’re doing something even though you’re just sitting at home.

Colin: No, I disagree. I can’t take podcasts. I can’t take it. I don’t know how you guys do it. You spend your whole life having these conversations. It’s draining to me.

Mark: It’s draining, but it does become a skill. You get good at it, and you start to polish your stories, then you figure out your voice or whatever the hell it is. It’s an art, and it pays well.

Colin: And does it help you with stand-up or hurt you?

Mark: Oh, it helps. First of all, it helps sell tickets like you wouldn’t believe, and then secondly, you come up with bits because you’re talking so much. You’re like, “Oh, that’s something,” and you write that down. Now you’ve got a bit. It helps in a little way, but it is exhausting.

Colin: Plus everybody has each other’s podcasts. The exhausting part is not you doing your podcast. It’s that you have to get your friends to do it, then you have to go do theirs.

Mark: Yes, yes, exactly. But if they have a fan base, now you get some of that. They get some of yours. Crossover.

Colin: It’s a verbal pyramid scheme.

Mark: Yeah. Yeah, exactly. Look at these LA guys. They’re millionaires. They all do each other’s. Bobby Lee does Theo Von’s who does Brendan Schaub’s who does Joe Rogan’s who does Tom Segura’s. I mean, it’s just incestual, but they make millions.

Colin: Yeah. No, I guess that’s a good point.

Mark: Yeah, well, nobody’s having real conversations anymore. And also, I think comedy is almost like a novelty now, like stand-up is so rote. There’s so little stimulus and I think people need that pod, because you can put it in your ear and you do the dishes.

Colin: Right, right.

Mark: This special, what’s cool about it, it’s almost more of a documentary, and it’s so much different than all the specials that are out now. First of all, it’s funny. And secondly, it’s just so cool, because nobody captures behind the scenes and the comedian mind like old Quinn here.

Colin: I would love nothing better than if we could do that as a weekly thing with just every comedian, because when you think about comedians—it’s always the take you have on something that makes it so interesting to me, you know?

Like anytime you ask a comedian a question—maybe most of the time—they won’t give you the common wisdom. They’ll give you their own angle on things. And you’re like, wow, that’s why I love to be around comedians. You know?

Mark: Because it’s all about the angle.

Colin: Yeah, the angle. Exactly. And that’s what I feel like, that would be fun to do that every week, you know?

Mark: Yeah, and we’d probably get more realistic. Because we have to really craft the joke, and it’s got to have a structure, and a setup, and a punchline, but if you really just got to the backstage and the hang, it’s almost like a podcast. You could really get to the meat of it.

Colin: Oh wow, I don’t want to hold myself to that high of an expectation. Almost a podcast, you say. No, yeah, no, you’re right. I mean it’s a combination. The funny thing about stand-up is there’s all the talk in the world, but then you’re, “Oh no, I got to go on.” And suddenly all my philosophies go out the window.

Because it’s like you got this crowd. They don’t care that you figured it out. They think you didn’t figure it out for them. And then you’re like, “Ahhhhh.” And all the audibles you have to throw. It’s really good in that way. It’s like going from coaching to suddenly playing in the game in the middle of your life every day, and that’s what keeps you honest. It keeps you humble, it keeps you honest, because you’re like, “Oh my god, I got to do this”—instead of just talking comedy, which we love. But then how many times have you been at a gig with some guy who’s like, “You know, comedy’s this,” and you go, “This guy really gets it. I love this guy.” Then he goes onstage. The biggest hack you ever saw in your life.

Mark: Yeah, because hack works. It gets laughs. And you don’t want to die up there.

Colin: But backstage, he’s Mr. Philosophy.

Mark: Of course, of course.

Colin: I remember in the ’80s, we’d always do the one-nighters in Jersey, every night. I was with this act, won’t name names—he’s probably dead anyway. But he starts talking to me, I haven’t met him before. But he starts riffing in the back seat of the car. I go, “This guy’s the funniest person.” We’re driving through Jersey. He’s riffing. I’m going, “This guy’s a comedic genius. I can’t believe it. He’s going to be …” Then he goes onstage. That was his act. He just did his act to me. In the car.

You’re like, ‘Oh my god, I got to do this’—instead of just talking comedy, which we love.

Mark: Oh, that’s crazy. What a psycho.

Don’t you feel like, I feel like stand-up makes you at least 30% less funny than you actually are, because you can be the funniest guy in the world, but when you go on stage, it has to be acceptable for this crowd of strangers that doesn’t know you? And you have to set the table, let them know who you are, where you’re coming from. And then it’s almost like food, where you have to set up a plate in a certain way so people will eat it. You have to put more sugar, more salt, more grease. And it makes you less funny.

Colin: Yeah. Well, do you mean it makes you less funny over time as a human being, or you mean–

Mark: No, in the moment. Because you have to cater to them so much that it makes you have to structure and change this and change that. But if it was just backstage and a camera was on you, and you didn’t know the camera’s on you, you’re way funnier.

Colin: Yes. Well, I mean that’s definitely what I was going for with Tough Crowd, and with this thing, which is trying to capture that other side, that merciless back and forth kind of banter that we have. When you go, “Oh my god, these people are so funny.” I’ve always been trying to steer something towards that.

Mark: Right. Yeah. And you nailed it, you nailed it in the new HBO Max special. It’s so good.

Colin: Thanks. But also, remember something. Everybody is funnier backstage. If you see a group of waiters getting ready to start a shift, they start talking about their shift they’re about to do, the manager, the customers, all the problems, you’ll laugh like crazy if you’re a waiter. Because it’s funny. It’s our whole business is being funny. It should be even more exponentially funny, you know?

Mark: I agree. But just like a waiter, when you’re back in the kitchen, you’re fucking around with all the other guys, it’s hilarious. But then you have to put on that waiter face, tuck your shirt in and say, “How are you this evening, Mr. Johnson, what can I get you?” And that’s the same with stand-up where, especially for me, a guy who’s not famous, every game is an away game. You got to bring it.

Colin: We’ll take that HBO Max special as an example. The reason bombing is such an obsession, it’s not only because it’s our biggest fear, because it’s not our biggest fear. We’ve all bombed so many times, it can’t be our biggest fear. We’re not psychotic. But it’s also because it brings out a side of immediacy, where you’re suddenly in the moment, and it’s so funny to us because there’s no interface. The waiter just dropped the tray of drinks. So now, all that façade is gone.

And that’s the beauty of bombing.

Mark: So sad times, this pandemic—we’ve already lost some comedy clubs. Dangerfield’s is done, which, I know Dangerfield’s was like a punchline, but I fucking love that room.

Colin: Well, the great thing about Dangerfield’s, I mean it might be the only good thing about Dangerfield’s, is it was like when you were a little kid and you were like, “I only wanted to swim.” Your parents go, “Here’s a swimming lesson.” Other people go, “We’re throwing you in the lake and we’ll be back in 30 minutes.”

Mark: I love that analogy.

Colin: You either learn to swim or you don’t, you know what I mean? They’d leave you up there and you better become a comedian if you’re not one.

Mark: You got that right. Yeah, completely, especially a queef like me, I’m coming out of Brooklyn and some bar show and I’m practiced. Then you go in there and it’s bridge and tunnel, maybe from Long Island and some lady with the big hair and huge cleavage, you got to figure it out.

Colin: If you know how to look at a certain room and bring a different energy, you’re not changing your intent or your jokes or your point of view. Somebody twists that and suddenly that’s the—I’ve seen pandering a thousand times and it doesn’t look like when you’re getting laughs. You know what I mean? You’re getting cheers.

Mark: Yeah, completely. It’s like when the white guy goes into the Black room and tries to be Black. Like no, just be your nerdy self. That would actually be more interesting.

Colin: Yes. Yeah, they have Black acts. They don’t need to see you doing a Black act. They want to see a white guy being himself, being a white guy.

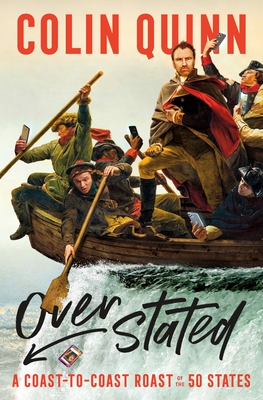

The book that Mark forgot to mention.

Mark: How much comedy are you consuming? You’re pretty on the pulse with everything.

Colin: I’ve been very bad lately because I’ve been writing. I’ve been writing all this other stuff that I want to work on because there’s no stand-up.

Yeah, but I mean, I love doing that other stuff only because I feel like if I could just be a producer … I’ve been doing stand-up for a long time. If I could be a guy that just works with stand-ups. Even that special, I tried to get out of performing that special, you know? I was like, “I don’t want to perform.” Then I don’t know why I was thinking they would let me. I was like, “Yeah, I’m not performing.” The man’s like, “No, you’re performing.” I was like, “Oh gosh.” I just wanted to do a behind-the-camera and see how it feels.

I’m more interested in you guys and your journey and what you guys are doing.

Mark: How funny for people at home to be like, “Wait, he didn’t want to perform? What? He’s a comedian. It’s his special. Why wouldn’t he want to go on?? That’s why comedians are so complex. That’s a hilarious thought. “I don’t want to go on. I just want to be in the back.”

Colin: Right. I mean, you have to do it for a thousand years before you feel that way, you know? Now I’m like, “Oh God.” I mean, I always wanted to go on. When I was at Catch A Rising Star. It’s the mid-80s, right? Comedy is relatively new. I remember one night Rodney Dangerfield went on. David Brenner or somebody like that and some other act who’s pretty big who killed. Then it was like six of us, we’re all the backups. They used to have backups in comedy in case they’re needed for the show. It was late in the show. There were no other regular acts. They go, “Who wants to go on?” We all raised our hand like, “I’ll go on.” You need to have that in common.

They’re the biggest acts in the country. You got 20 minutes of mediocre shit. “I could do it.” You need to have that personality like, “I’m as funny as anything I just saw. I’ll kill, too.”

To last, you have to be like, “Yeah, fuck, yeah.”

Kevin Meaney, Colin Quinn, Mario Joyner, Stu Trivax and Chris Rock at Catch A Rising Star in New York, also home to Seinfeld, Joy Behar and countless others

Mark: Totally. Great point. Yeah. Remember Ronnie Shakes? I used to love that guy.

Colin: Oh my god. We were just talking about him. Hilarious.

Mark: Hilarious. Brilliant. Philosophical, almost Woody Allen-esque but then with a great turn at the end. He had a good look. Man, he was great. Sad that he’s not around.

Colin: I knew him well. He went on the road. I think he was in Akron at a comedy club and went jogging, died of a heart attack, right there. You know, middle of his career, just doing a weekend. Went for a jog, and a heart attack. And he was so funny. I was going to bring him up earlier. I remember one friend of mine going to me, “Hey, that guy’s kind of an old-school hacky guy.” I go, “No, he’s not, he’s not. It’s just the opposite. He’s ironically doing that one line of cadence, but he’s telling you brilliant things.” Not everybody understood what he was doing. It seemed like a Shecky Greene-type thing. It seemed like a Henny Youngman style. He was making fun of it while he’s doing it, too.

You remember this joke? He goes, “I tried to kill myself once. Tried to drown myself. Went to the beach. I don’t know how serious I was. I brought a towel.”

Mark: I love that. That joke has 38 layers to it. It’s so deep. I love that joke. And he did that on Carson, I think, that’s a suicide joke and everybody’s applauding.

I mean, he was so different to me. He was so weird. I was a big fan. I brought him up to Seinfeld once and he was blown away that I knew him, but, he’s good. Every joke is a 9 out of 10.

Colin: That was the thing. What he was lacking, not to speak ill of the dead, was—even I’m the same—if I’m watching him do an hour, at the end of 40 minutes I’m like, “Okay, I could be reading a joke book. I want to know a little more of you.”

Even if a guy like that doesn’t have to necessarily expose himself fully, I want to see you work the crowd because you are so quick. He was a really quick guy. Obviously, you couldn’t write those kinds of jokes if you weren’t.

Mark: Yeah, no, you’re right. You’re right. I mean, I’ve always—now we’re getting real deep into comedy theory, but I think if you’re going to be a one-liner guy, you have to have a huge persona.

I mean, look at Steven Wright. Weirdo, monotone, balding. Jeselnik: handsome, super dark, super competent. Hedberg: long hair, hippy-dippy druggie. You’ve got to have a huge persona because otherwise, you can’t sustain for an hour. It’s just one line after another.

Colin: What about the ultimate: Rodney?

Mark: But here’s the thing about Rodney—it was all personal.

Colin: Yes. But you felt his pain the whole time he was up there.

Mark: Yes. Yes, exactly.

Colin: Those old school guys were kind of detached. Like Henny Youngman was like, “My wife…” he had no emotions. He had no feelings about his mother-in-law, he had no feelings about his wife. He had no feelings about her cooking being bad. Rodney felt pain in every moment of every bit of it.

Mark: Right, right, so true.

Colin: The great thing about Rodney was his segues were so funny. Because on the one hand, he’s like, “It ain’t easy, it ain’t easy,” for anything. “You go to the grocery store—that ain’t easy.”

So he’s doing a segue that’s really obvious, and he’s making fun of the segue at the same time. You see him on Johnny Carson, he’s like, “Johnny, you know. You know, I don’t have any luck with that. I have no luck.” He’s making fun of it, but at the same time, it’s the segue that is actually the ultimate truth of what he’s conveying, which is that it’s brutal.

And the jokes still have to be great jokes. When his jokes were not great, he sat there and bombed. But all that stuff with a great joke, that’s when you have a great act. There was nobody even close. I mean, and his movies were funny.

Mark: I think he’s one of the best of all time, but he kind of gets forgotten sometimes. I think, because he’s so goofy. He’s got the big eyes, the neck twitch, the necktie adjusting. But to me, his body was like an instrument. He looked perfect. He sounded perfect. He dressed perfectly. It’s almost like he had to just look in the mirror and go, “Not only am I going to write a great joke, but my body will become part of it.” He couldn’t do jokes by being confident, because it wouldn’t match. But yet he figured out a way. That’s probably why it took so long to figure it out.

Colin: You know how he was a salesman, and he tried stand-up and he was like Lenny Bruce— kind of a hip, pot-smoking guy. He was totally that whole crew, as Jack Roy. And then he went away, went back into aluminum sales at 38 or 39. But something just hit him, no respect, and then that was it.

Mark: All right, all right. Here we go with the interview. Let’s get cooking here…