One of the World’s Foremost Experts on Deep-Sea Life Explains Bioluminescence

Turns out texting is not the most common form of communication on the planet. In fact, the winner has nothing to do with humans, and everything to do with creatures that can glow in the dark. There are a rather large number of animals on our planet that make light, and most of them are in the ocean. Edie Widder is the CEO and senior scientist at the Ocean Research and Conservation Association, and the leading scientist in this light-show phenomenon. She’s been researching and exploring bioluminescence in the deep sea for the past 15 years — her discoveries have (literally) shed light on the depths of the oceans we’ve never seen before. And since she was the first to ever capture video footage of a never-before-seen giant squid, if we were going to ask anyone why anglerfish have that lightbulb on their heads, it was going to be Edie.

What is bioluminescence?

Edie: A natural phenomenon that occurs when two animal-made chemicals are mixed and they produce a cold, chemical light.

But where?

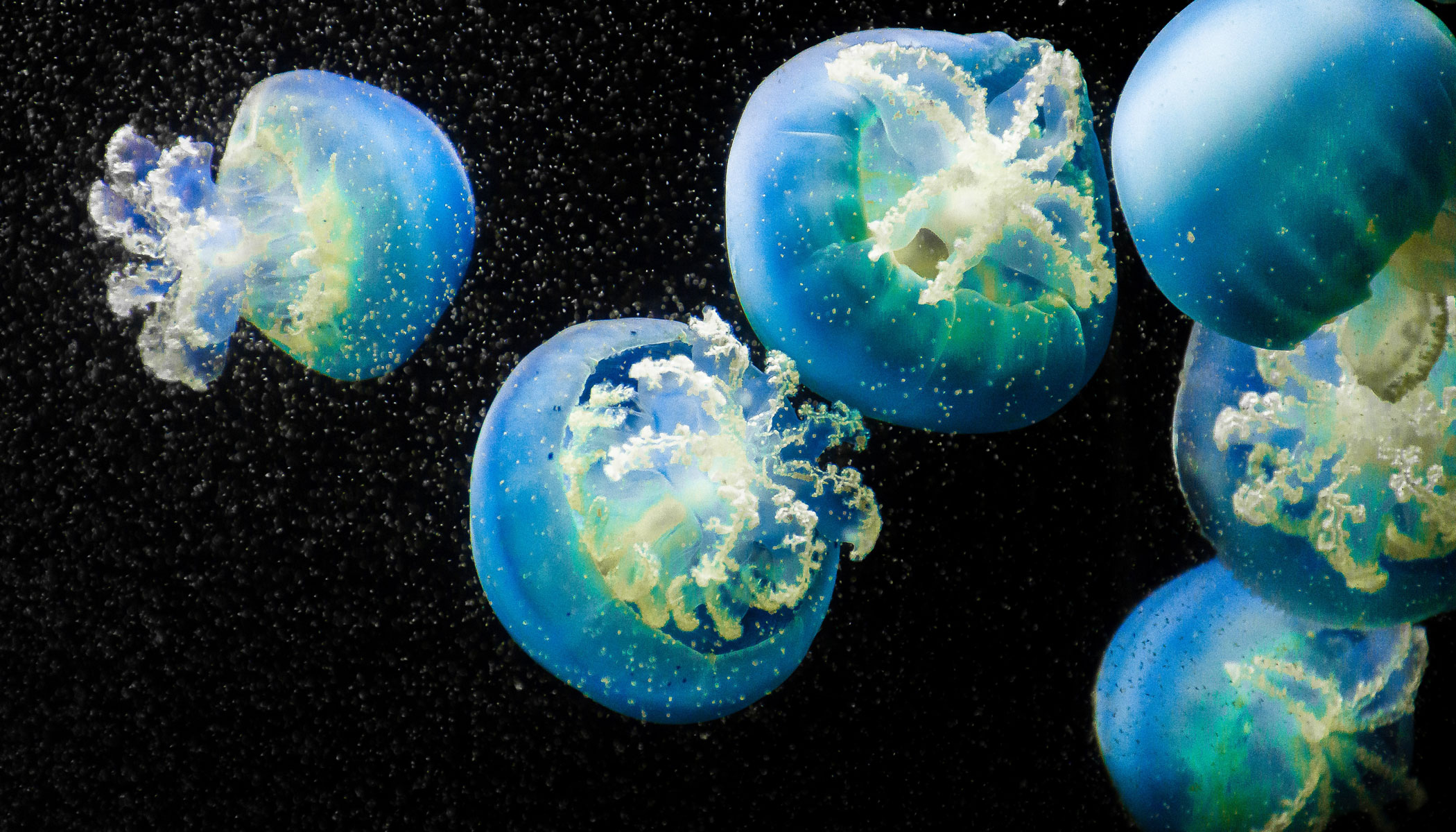

Edie: Every cubic meter of the ocean. From surface to bottom and coast to coast. The most common place you’ll see it is on the surface of the ocean. Referred to as sea sparkle and named accordingly, these plankton and algae turn beaches into sparkling, glowing, beautiful artwork.

But why?

Edie: Bioluminescence is the most common form of communication on the planet due to the vastness of the open ocean environment. With built-in flashlights, animals use bioluminescence to help them see in the dark, using it to find food and lure in prey.

That explains the anglerfish. Animals use bioluminescence to attract mates by showing particular flash patterns only recognizable to their own species. As a defense mechanism, animals can squirt out glowing chemicals into the faces of their predators to distract them as they escape into the darkness.

It’s also used for camouflage, which may not make sense when you think about something that glows in the dark trying to blend in with pitch blackness. With light organs on their stomachs, animals use bioluminescence for counterillumination, allowing them to hide in plain sight. They obliterate their silhouette with bioluminescence that exactly matches the color, intensity and angular distribution of the downwelling sunlight so a predator looking up from the bottom can’t see there’s food swimming above. Even if a cloud dims the sunlight, the animals can maintain a perfect match.

“On my first solo submersible dive, I turned off my lights and was surrounded by bioluminescence. It looked like Van Gogh’s Starry Night

But how?

Edie: Evolution is like an arms race. Once vision evolved, defense had to evolve—either to outrun your predator or hide from it. But there’s no place to hide in the open ocean, so the deeper and darker, the better. The only problem is, the deeper you go, the less food options you have. This is where we see vertical migration—the most massive animal migration pattern on the planet, and also the most frequent. It happens every single day in the world’s oceans: As the sun rises, animals go down and hide and as it sets, the animals come up and feed in the safety of the night. Spending all their time in the dark has its effects. For any creature, from fish to humans, it’s pretty hard to see in pitch black, so enhancing their visual signaling capabilities for their new habitat was a must. They developed more sensitive eyes and bioluminescence to help navigate the depths.

But what color?

Edie: Most of the animals in the water can only see blue light because it’s the color that travels the farthest through seawater. Hence why everything looks blue under the surface. And most bioluminescent animals can only emit blue light. Except for one fish in particular. The stoplight fish. Aquatic creatures at lower depths don’t even have receptors for red light waves. With a big red light organ under its eye (explaining the name), this fish can not only see blue light and produce blue light with a blue light organ beside its eye, it can see and produce red light. Because it can see red and no other creatures can, it uses it like a sniper scope to be able to sneak up on animals that it can see, but they cannot.

We used the science of the stoplight fish’s red light to create a camera that could record these deep-sea creatures without them knowing we were there. Imitating a blue light-emitting jellyfish as a lure, the very first time we used the Eye in the Sea camera in the Gulf of Mexico, we recorded a squid that was completely new to science just 86 seconds after we turned it on for the first time. It couldn’t even be placed in any known scientific family.

What a sucker.

Edie: We were able to capture an octopus we called the red balloon octopus at the time—for good reason—it had webbing between its arms and it would shape itself into a big red balloon. When we were studying it, it was behaving very strangely for an octopus. Normally, they’d be glomming onto the side of the tank with their suckers. Not this one. It was just morphing into bizarre shapes. It wasn’t until it wrapped all its arms behind its head that we noticed it’s suckers weren’t like suckers at all. They were light organs. Like little pearls. We took it into the dark and sure enough those suckers were twinkling. We found those light organs used to be suckers, but had evolved into bioluminescent organs. Evolution caught in the act. No longer the red balloon, but the glowing sucker octopus

What else?

Edie: We’ve explored so little of the ocean, anytime we can discover and highlight real, obvious evidence of how little we understand about the ocean for the public and the policymakers, it’s valuable and worthwhile. We’ve been trying to emphasize this with the giant squid recordings. The fact that something that can grow as tall as a four-story building remains unseen in the depths for so long despite so many expeditions is just a very small indication of how little we’ve explored and how little we understand our ocean planet.