An interview with Wavy Gravy

Community seems to be the ultimate goal of the hippies. We’re not positive because we failed to talk to every single hippie prior to the publication of this issue but we’re pretty sure it’s community. Or at least a strong sense of community. And that means bringing people together—just like Mr. Wavy Gravy. And in our book, that would make him one of the most influential hippies we have come across.

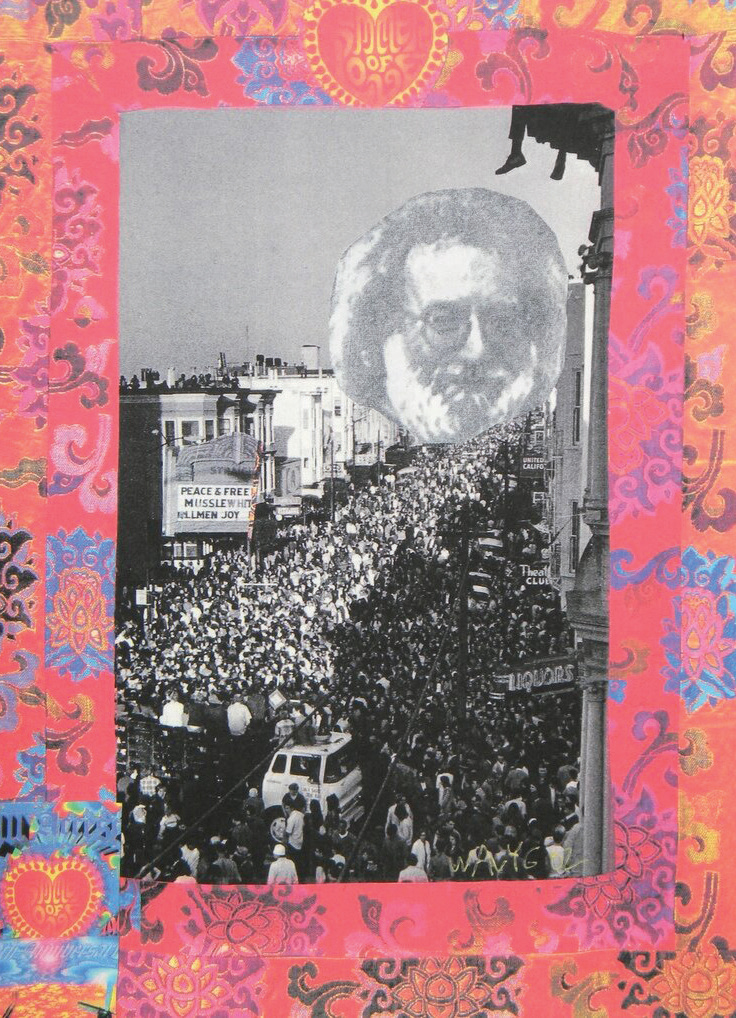

Wavy has been down many roads over the years but here are a few—he was a stand-up and a free-form comedian of the ’50s in New York City. A trip guide in the formative years of the West Coast hip scene. Friends with Ram Dass, Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia. Steward of the Electric Kool-Aid and Merry Prankster/Grateful Dead days of mid-’60s San Francisco. Founder of Hog Farm, Camp Winnarainbow, Seva Foundation and other initiatives. A volunteer worker/entertainer in hospitals for brain-damaged children.

A good-humored peacemaker at all the major rock festivals and political demonstrations of the ’60s and ’70s including a stint as the “security team” at Woodstock. Organizer of the hilarious “Nobody for President” campaign in 1976. The visionary promoter of Earth People’s Park, Feed the Hungry and other utopian dreams.

Wavy Gravy was kind enough to sit down with Whalebone for The Hippie Issue and share a couple tales from the road.

Whalebone: Okay, camera rolling.

Wavy Gravy: Let it rip. Blast off.

WB: Where does the name Wavy Gravy come from?

WG: I was born Hugh Romney and after Woodstock, we went to do the Texas Pop Festival in Lewiston. And that’s where I bumped into B.B. King on the free stage. I was kind of laying there listening, and somebody said, “B.B. King is here with his bus. He’s going to play for free. Can we clear the stage?” And I looked around, there’s nobody there but me and I started to get up really slow and I felt this hand on my shoulder. I looked up and there was B.B. King and he looked down at me and said, “You Wavy Gravy.” And I don’t know where that came from. It just popped out of B.B. and landed on me. And I’ve stayed Wavy Gravy ever since.

WB: How did you find yourself at Woodstock?

WG: We were driving around the country, mostly from college to college being sponsored by usually the Interfraternity Council and the local hippies. And we would appear on campus and set up events where we’d get hundreds of people working on one giant painting, or we had movie projectors and microphones and just all kinds of explosions of consciousness. And we got this call that they would like us to come to New York state and do this music festival. And how could we say no?

Nobody ever expected there would be 400,000 people. One thing that came out of Woodstock was this saying I apparently did after the first night, where I achieved some notoriety, I got on the main stage and to the entire crowd I said, “Good morning. What do we have in mind, campers? How is breakfast in bed for 400,000?”

Somebody who encouraged people to put their good where it will do the most and let the wind blow through their hearts and do that thing.

WB: It seems like a couple of people would say that it was a success.

WG: I guess so. It was fun.

WB: What is a hippie?

WG: I think that a hippie is me. They’ll bury me a hippie. A hippie has peace, love and understanding. That’s how I roll my life and it lights up my heart—you just follow that light in your heart and you’ll never go wrong.

WB: What’s the importance of following that light?

WG: Well, my line of goodness that I got from a great writer, somebody who innovated my life named Ken Kesey (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) is:

“Put your good where it will do the most. And that’s how you help people. And you don’t help people, you help people help themselves.” Like people would say to me, what are you into? What lights up your heart and follow that. And you never go wrong.

WB: Once upon a time, there were two gentlemen from Vermont and apparently, they had a really big thing for ice cream. So they started an ice cream company. It’s a good group of folks. And apparently, they were encouraged by you enough to name an ice cream flavor after you. What’s the story? How does a person get a Ben & Jerry’s ice cream named after them?

WG: I was going across the country to speak at a commune in Vermont and I was kind of hitchhiking along the way and I got picked up by Ben Cohen. And in the car, he said that he and his partner Jerry wanted to make an ice cream out of me, Wavy Gravy. And I thought “I love ice cream.” And to be one, can’t get much better than that. It was a Brazil nut with some coconut and chocolate and it was an amazing flavor—I remember I was in Vermont and when all the truck drivers were heading out with their semitrucks full of Wavy Gravy ice cream—I got them all to lay down on the floor in this big auditorium and put their heads on each other’s stomach and do dessert mantra, which I created called YUM! And they all started going “Yummmmm. Yummmmm.” All these truck drivers.

WB: Can you tell us about some of the organizations you are involved with and helped start?

WG: I think you must be talking about the Seva Foundation, which is a Sanskrit word that means “service to humankind.” And this was created by Ram Dass, Larry Brilliant, myself, and this amazing woman named Nicole Grasset who was one of the leaders of the eradication of smallpox.

It was Nicole that came to our circle and said that we ought to take on blindness because 80% of the people in the world that are blind don’t need to be blind and get their sight back after a simple surgery that takes about 15 minutes and cost about 30 bucks, maybe 20 when we started and now it’s 50. But it became my task to get artists to perform for no fee to make blind people see. And because of my relation with Woodstock and other festivals, I had access to all kinds of incredible people that make music. And I started out with Jackson Brown and Bonnie Raitt and gradually began to build more and more people until, thirty or forty years later, we’re over 5 million people who are not bumping into shit because we saved them.

WB: And what about this wonderful camp?

WG: Oh, well sure. My own explosion of consciousness occurred around kids. And I had a young son named Jordan. His early name was Howdy Do Good Tomahawk Truck Stop Gravy Romney. And when he was seven or so I got together with a friend, who was a theater director, and I did theater games and we exploded the thing that turned into something called Camp Winter Rainbow, which is a circus and performing arts camp where kids learn to juggle and tight rope and do theater. And it just expanded and expanded until kids from

7 to 15 get to come to camp for a month and pick different things to do. They make choices for an hour in the morning, and then a conch blows and then they go to their second choice for an hour. Then they all meet you in the circle after their classes and they get to get on stage and show each other what they learned that morning. And then they would go to lunch. And after lunch is a free time for swimming at the lake, which we called Lake Veronica. This was a 700-acre ranch in Laytonville, California, where we did the camp.

WB: Before the camps, you spent some time in New York City. How was Bob Dylan as a roommate?

WG: Well, he wasn’t exactly a roommate. We shared a room up over the Gaslight at 116 MacDougal Street, which is where performances would occur. Upstairs there was this room where people would hang out while they waited to go on. And that’s where Bob Dylan wrote “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” on my typewriter.

People used to perform for each other there too. At the end of the evening performances, they would all gather and they would fill the place and perform for each other. That was a glorious time in creativity.

WB: Are you the official clown of The Grateful Dead? Do you know what that means?

WG: I’ve heard that. They’re friends of mine and the label has been applied to me. And my motto is “Toward the Fun”—that’s the camp motto also and my ice cream flavor.

WB: How would you like the world to remember Wavy Gravy?

WG: Somebody who encouraged people to put their good where it will do the most and let the wind blow through their hearts and do that thing. And everybody’s thing will be different and let’s celebrate that difference. Can you put your good where it will do the most? That’s the best advice I can give anybody.

I’m trying to know nothing, because nothing lasts. That was the sign over the door on the good bus, as you exit the bus, the sign over the door said, “nothing lasts.”