On Finding a Time Capsule in a Time Capsule

Written by John Capone

Things you should attempt to collect before reading this story:

- Four to six friends

- An OG copy of Maggot Brain by Funkadelic (1971) on vinyl

- Any decent copy of Anthem of the Sun

- Turntable and vintage speakers

- One sheet high-powered blotter acid

- A time machine to go back to 1993

- Some quarters for the slot machines

Your brain is floating in a void, churning with the things you think you know.

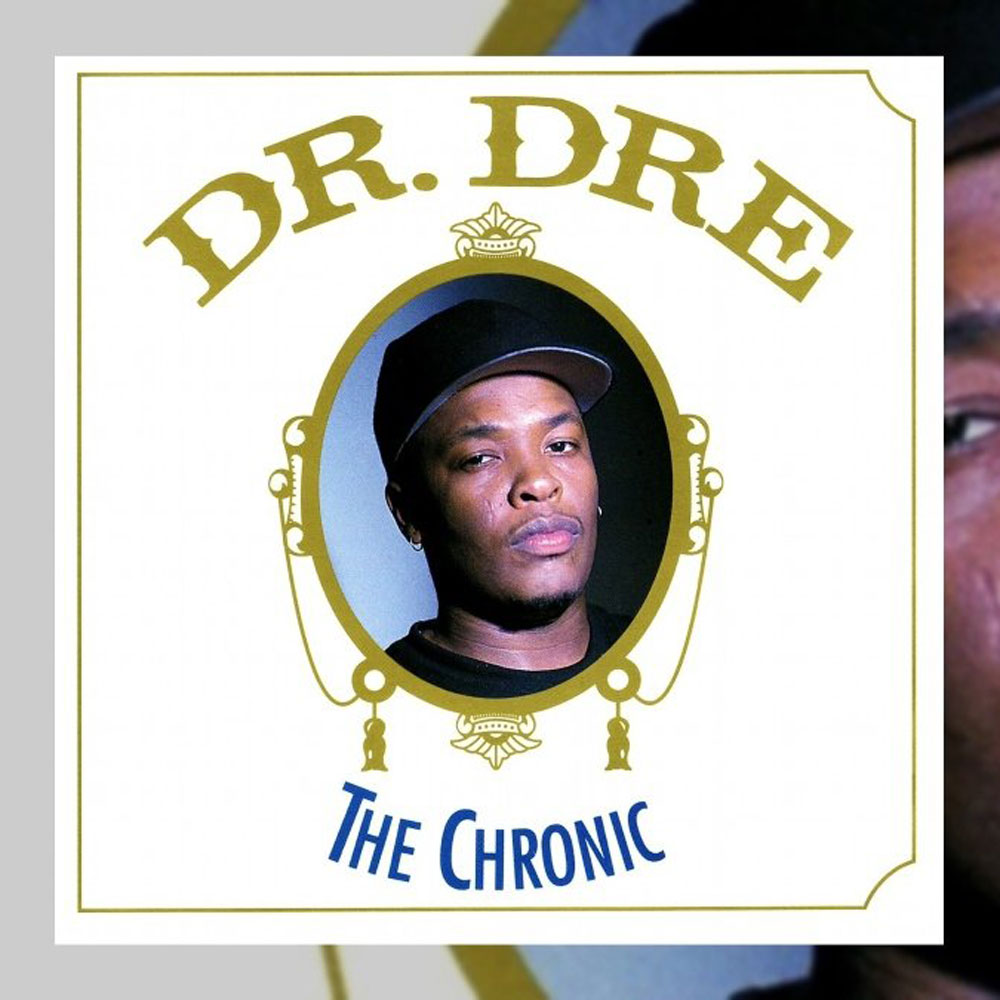

Sure, you knew P-Funk and George Clinton’s band of merry ’70s funksters had formed the basis for everything from Digital Underground to Paul’s Boutique and provided the literal blueprint for G-funk and Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, which had taken up permanent residence in everybody’s CD changers alongside Mazzy Star and Portishead the summer before. But in 1993, I had never heard of Maggot Brain by Funkadelic, an album that owed as much to Detroit soul singles as it it did the Grateful Dead and Jimi Hendrix and one that, like so much great literature, would take decades to be fully appreciated. Despite pulling pieces from Isaac Hayes’ Stax-Volt studio sessions and melding them to scuzzed-out grooves that approximated what MC5 or Blue Cheer might sound like jamming with The Dramatics through a kaleidoscope that fixed one part Haight-Ashbury psychedelia onto a lens of rock solid boogie and took it to church, the album sounded like none of those things at all, I’d learn one weekend that year. George Clinton had his eye on the future long before he ever launched the Mothership.

That weekend we were attempting to break the cycle of Magic Hat 12-packs and ziplock baggies of Mexican swag that passed for recreation in the dorms sophomore year at the University of Maryland and get away from the hubcap in the center of the apartment filled with cigarette butts and old roaches by taking a weekend retreat. Which meant a sojourn to somebody or other’s uncle’s dilapidated shack in Ventnor Beach. Like most of Ventnor, the place looked like it hadn’t been touched since around the time the state of New Jersey pretty much gave up on the town and adjacent Atlantic City ever being any kind of seaside resort again in 1978 when they OK’d the casinos that never brought much if any money back into the communities.

We’d packed five or six of us up for the drive up the coast—among us a Deadhead on the university diving team, an art major who we always made fun of for being an art major until graduation when he spent the next year restoring frescos in Italy while we were all bartending, one friend who had just returned from a motorcycle trip to San Francisco like Neal Cassady 30 years too late, and another acquaintance who never seemed to attend any classes but did bring a sheet of high-powered blotter acid.

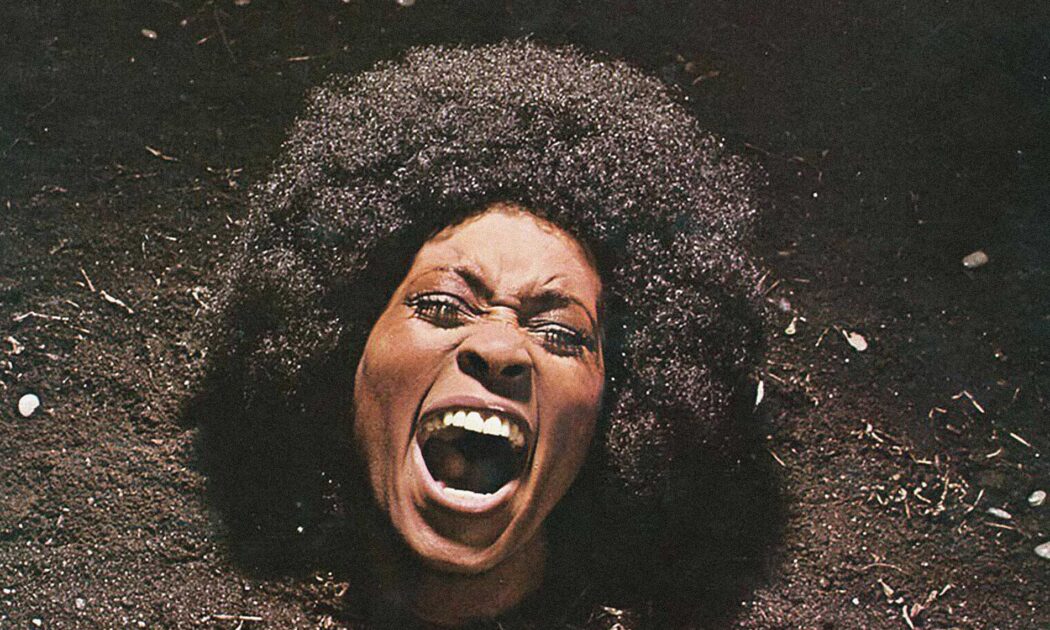

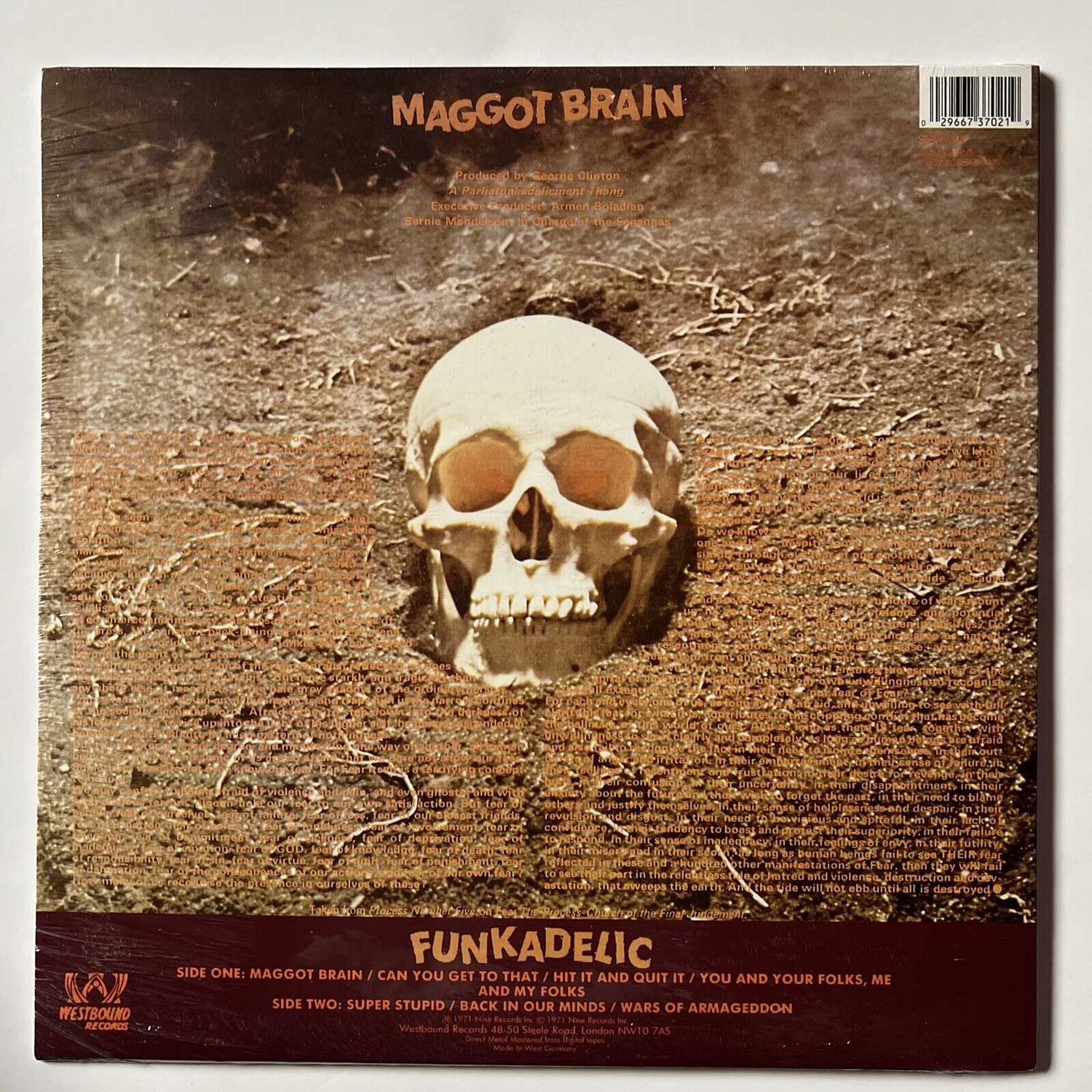

The place was too small for all of us. And there was a skirmish over someone using someone else’s toothbrush at one point. But, despite this, we did not leave the tiny cabin for two days. A big part of the reason was the copy of Maggot Brain we’d found tucked into the shelves and which we blew the dust off. You might be transfixed by the cover, a close-up of a woman (model Barbara Cheeseborough) with an afro buried up to her neck in dirt and screaming. When you flipped it open, the right side showed a photo of the band standing in what appears to be an alley, and the left flap was dedicated mostly to a close up photo of an actual maggot and an essay on fear from the Process Church of the Final Judgment, a satanic-Christian sect. On the back, poor Ms. Cheeseborough has been reduced to a skull. You had no idea what it could sound like but felt compelled to find out. It looked like it might be a heavy metal album. The heavy part was right.

Clinton once told an interviewer that he looked around at the popular music of the late ’60s and early ’70s—The Rolling Stones and John Mayall and Cream and Peter Green and Led Zeppelin—all the white kids listening to English bands resurrecting old blues licks from 30 and 40 years before, and he said that’s what he was doing. Not what the English bands or the white kids were doing, but what the bluesmen had done decades before. Going down to the crossroads. He said he was making the music that the white kids would be listening to in 30 or 40 years. He said this around 1971. Listen to “You and Your Folks, Me and My Folks,” the final track on side one of Maggot Brain, and then ask the Beastie Boys if he was right.

Maggot Brain, early days for George Clinton, was at that time, and in some ways still is a forgotten masterpiece. In 1993, it had never gotten a proper reissue on vinyl. It still has not. Too weird, maybe. Too far off what people had come to expect from Clinton. But you can bet your favorite musicians listened to it and it has reverberated in the decades since its release, leaving ripples in everything from Prince to Metallica. Jack White even launched a magazine named after it. The OG vinyl on Westbound Records will now run you north of three bills—if you can find a clean copy. There are bootleg vinyl reissues, usually either recorded from an old vinyl copy or ripped off a CD, and they sound about how you’d expect. Thin and tinny with none of the deep groove and power of the original recording, which feels like a tactile thing the way the grimy throb and thump of Serge Gainsbourg’s Histoire de Melody Nelson does. In 1993, it was the exact sort of thing you’d find only in a house in Ventnor Beach, New Jersey, waiting for you to discover.

So, you drop the needle.

The album starts with a few auditory echos of droplet kind of noises—the sort of thing you’ll find all over the Grateful Dead album Anthem of the Sun, where the band was really trying to bring the psychedelic trickery of their live shows to the studio with decidedly mixed results. Those droplets echoing in your brain might linger while you lean in closer. Then a booming voice—the voice of god or your conscience but actually George Clinton—intoning “Mother Earth is pregnant for the third time, for y’all have knocked her up,” definitely gets your attention. And then god slash George Clinton tells you, “I have tasted the maggots in the mind of the universe.” What?

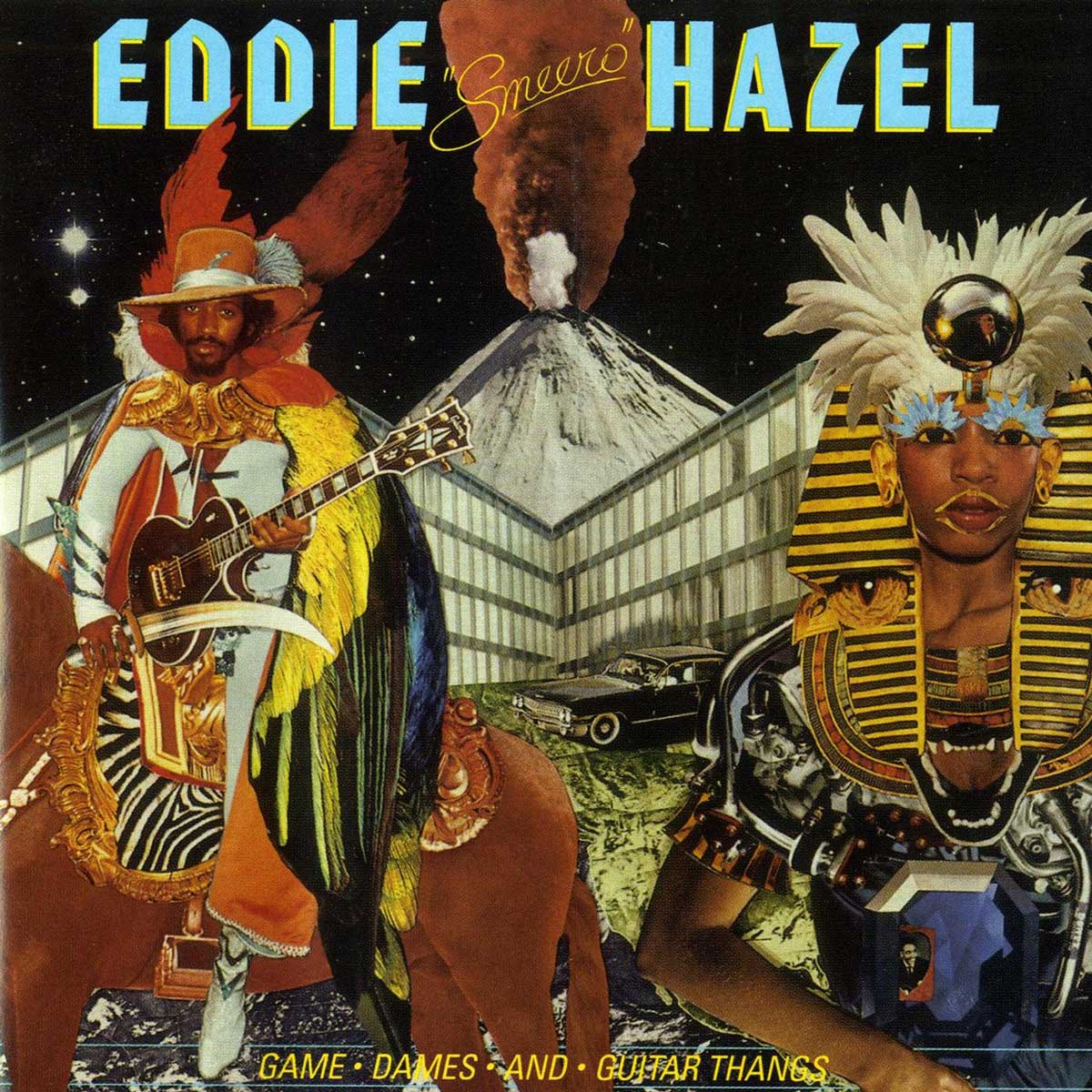

It then launches into 10-plus minutes of guitarist Eddie Hazel just absolutely shredding, backed by a Bernie Worrell organ line and not much else. There is no characteristic Funkadelic bounce (that comes on the next two songs, albeit in early form) or the ensemble troupe that later would fill stages with upwards of 15 people playing at a time—Bootsy Collins and Maceo Parker were still backing up James Brown. No vocals even. There’s only Bernie’s lonesome, trembling organ and Eddie’s guitar locked in an intimate embrace. The wailing of the guitar goes on and on, ringing and drenched with reverb—you cannot stop listening to it. It’s in conversation with itself, sometimes dropping into bars of deconstructed blues, sometimes sounding like nothing you’ve heard, but mostly just wailing. You can’t help but think it sounds exactly like what the cover promised.