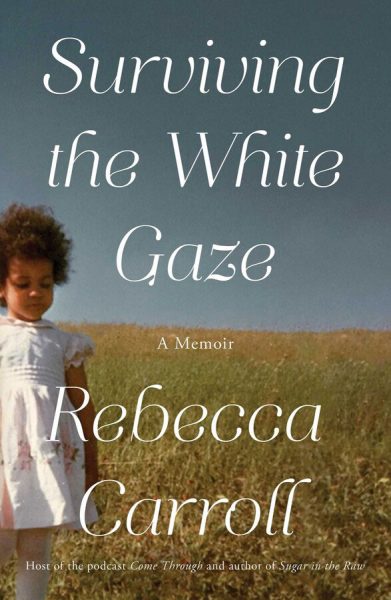

Sasha Sagan, author of For Small Creatures Such As We interviews Rebecca Carroll, cultural critic, author and podcast host

I met Rebecca Carrol l almost 15 years ago. She was the host of a show about documentary filmmaking for the teeny, tiny TV network where I worked as a junior producer. She was a newlywed and new mom, glowing, bright, hilarious, with a kind of cheerful irreverence to which I was immediately drawn. I knew why I instantly admired her. What I didn’t know was the astonishing story of her life. As we transitioned from colleagues to friends I learned more about her story. She was adopted by a white family living an unconventional life in small-town New Hampshire, where she grew up the only Black person for miles. In the time since we met, Rebecca became a celebrated cultural critic, in her role as the editor of Special Projects at WNYC, in the pages of the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, on her podcast “Come Through” and beyond. Then, a few weeks ago I got my hands on an advance copy of her emotional , enlightening, un-put-downable, cinematic new memoir, Surviving the White Gaze. It deftly explores race, coming-of-age, relationships, deeply complex family dynamics and even abuse. Now I feel like I’ve lived her life story with her. And I’m even more full of admiration for her than I was when I met her.

–Sasha Sagan

Sasha Sagan: Your new book, which comes out in February, is so vivid. It made me wonder, do you secretly have a photographic memory that you never told me about?

Rebecca Carroll: Well, here’s the thing, I certainly could not have written it in such vivid detail had I not been a sort of obsessive, diligent journal writer. Starting from a very, very young age — that piece that I talk about in the book of that essay, “I Am a Black Child.” I still have that. I knew very early on that I was going to put to paper my thought process. I look back at some of those early diaries, which were like, “Today I had ballet. Good night.” It wasn’t that heavy, but I was devoted, I was committed. Also, though, my childhood was vivid. It was every single bit of that kind of rich, colorful, fragrant, kaleidoscopic art. I can still smell in my mind the art books that we had.

Sasha: Your book is so honest and real. The reader is there for the beautiful parts, and the heart-wrenching, really difficult parts. I can’t help but wonder if there are things that you hesitated to include?

Rebecca: Yeah, I struggled a little bit with my parents’ open marriage. Not because it was [a secret], everybody knew. But I probably wouldn’t have included it if my father’s lover weren’t such a central character for me. The way she looked at me and in proximity to my father, that dynamic really informed the way I felt about relationships and men and emotions. I was extremely close to my dad. One thing that I didn’t write a lot about was our relationship. I’m still figuring out the loss of that relationship in some ways, but there’s a scene in the book [where I am] standing in front of his desk and just feeling like I was at the altar of all that mattered in our family. And then all of these years later realizing that was just sort of the design of it. When you try to reconcile with the humanity of a person, it’s hard.

Sasha: There’s so much nuance in all the relationships that you write about. You communicate that ability to hold both realities of what a person is like. For somebody who’s reading who is maybe a Black kid in a white family, in a white town, in a white world, what would have been helpful for you to hear? And what would you want to tell white adoptive parents of Black kids?

If it had been accessible to me then, I would have had to be encouraged because I was being raised through the white gaze.

Rebecca: There are a lot of anecdotes from the time that [my son] Kofi was born till now, where he tells me what I needed to have heard. About a year or two ago, we were talking about schools and I was saying how important it is to me that Kofi goes to a school where he has Black teachers, but also peers and mentors and so on and so forth. He said, “You’re obsessed about this.” Yes, I know and I said, “Name three Black role models you have.” He was like, “[my friends] Caryn, Dorlan, and you.” I was like “Damn.” I didn’t even realize. I am enough for him in terms of Blackness.

Sasha: That’s so beautiful and it’s such a credit to you… obviously, the internet, social media, all of that stuff is such a double-edged sword, but it makes it so much easier to find a community, even if it’s not in person. I wonder what your experience would have been like if we had that technology then.

Rebecca: That’s such a great question, and I think as an adult, it’s really meaningful to me in terms of community and Black folks on social media and on Black Twitter and all that. But if it had been accessible to me then, I would have had to be encouraged because I was being raised through the white gaze. You know, The Oprah Winfrey Show was on, and Good Times was on, Diff’rent Strokes (terrible show by the way) — there were Black people on television, but the emphasis, the standard was whiteness. I mean, I felt secretly guilty for loving The Wiz. I loved The Wiz. It felt like a secret I had to keep.

Sasha: On your podcast, “Come Through,” you’ve had epidemiologists, religious leaders, Issa Rae, Julián Castro, Ava DuVernay, an enormous range of people. What has been the most surprising part of those conversations for you?

Rebecca: I’m going to call up James Baldwin here. One of my favorite quotes from him is that everything is happening for the first time, the only time. I try to create that in every conversation. So I’m going to use the example of Ava DuVernay, not because it was the best interview, because it was short and she didn’t have a bunch of time, but I said, “People have said to me what a terrible time it is to be Black.” And she was really floored by that. She was like, “What? People don’t say that to me.” I was like, “Yeah, people have said that to me. How would you respond to that?” And she was like, “Well, I would have to pick my jaw up off the floor.” She was really taken by that and I was kind of amazed that as a Black woman in the Hollywood industry she had never heard that. So it’s just trying to create a moment for both of us that happens for the first time.

Sasha: There is that Danzy Senna quote that goes, “Every work of American literature is about race, whether the writer knows it or not.” I think about that a lot in the context of your podcast. What do you say to people who don’t see it?

Rebecca: So here’s the beautiful thing about getting older and surviving the white gaze: I don’t feel any obligation whatsoever to explain. The work that I do, the writing, the podcast, do with that what you will. The tools are out there. It’s my life’s work putting it out there for you.