Photo by Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

The Philosopher of Fungi

@paulstamets x @merlin.sheldrake

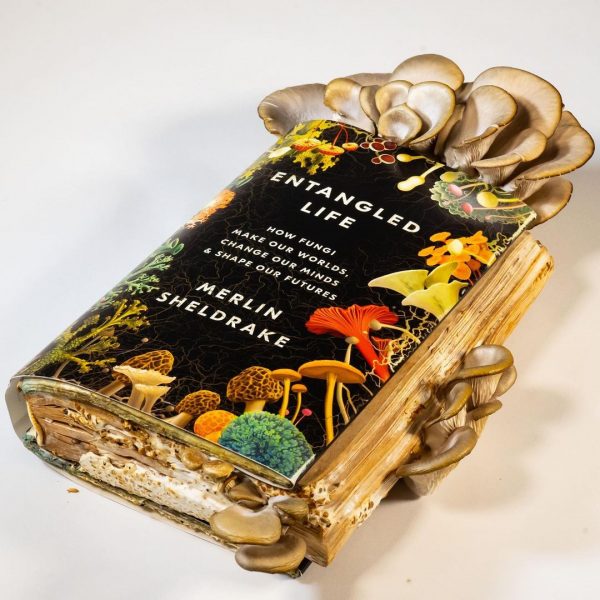

Mycologists tend to be an odd mix of laboratory scientist, naturalist and shaman. Mycologist Paul Stamets definitely fits into all these categories and probably a few others that are not quite so easy to label (there’s even a Star Trek character named for him). He chose to interview biologist and writer Merlin Sheldrake, who might not have Stamets’ decades of experience quite yet, but brings an academic rigor to fungal research. Sheldrake received a Ph.D. in tropical ecology from Cambridge University for his work on underground fungal networks in tropical forests in Panama, where he was a predoctoral research fellow of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. In his recent book, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures, Sheldrake explores the fungal world, and all the different and interconnected ways that we relate to it and it relates to us, and, as Merlin puts it, “might have shaped our existence in ways we don’t know about.”

Paul: Merlin, you and I have known each other since you were just a little pipsqueak, so to speak. But why don’t you tell us for Whalebone readers how you got involved in the field of mycology and what inspired you?

Merlin: Fungi are so connected to so many aspects of our lives that you don’t have to look far to find a path that will take you to a fungal answer. One of the reasons I got interested in them when I was younger was my interest in symbiosis, and the often surprising ways organisms find to live alongside each other. And fungi are such master symbionts, they play such big roles in symbiotic associations that have shaped life on Earth. So, my interest in symbiosis led me to fungi very quickly, and that’s what took me to mycorrhizal fungi.

Paul: Encountering fungi and mushrooms in nature to me are like a window into the mycelial underground. When these mushrooms pop up, it’s really showing you, for the first time, what you can’t see unless you go into the mycelial underground. There was a recent article talking about how mature and old-growth trees, their health is greatly enhanced by the plurality of fungal species. What is science now showing us?

Merlin: This recent study is illuminating because it shows us the impact that these shared fungal networks are having on mature trees. It’s something that’s been quite hard to access until now. And the correlations that it finds suggest that the more different fungal species or genotypes that the plant is connected to, the more it grows.

And this makes sense when you think about it, because these fungi can be behaving in different ways. There’re so many ways to be a fungus.

Paul: And so the natural question is, what about this crosstalk of communication between these guilds of fungi and the tree? And can you say therefore that a tree cannot be defined unless you also define the whole communities?

Merlin: Absolutely, we can’t think of a tree without also thinking of all of the microorganisms and fungi that co-exist with that tree. After all, these fungi have played such a key role in the evolution of plants on land in the first place: their evolutionary stories are completely entwined. Only with the help of mycorrhizal fungi did the ancestors of land plants make it out to the water in the first place. So when you hold a plant, you’re holding the outcome of a fungal relationship with a plant and when you eat a plant, the same; when you touch a plant, the same; when you cultivate a plant, you’re cultivating a community.

Paul: I’m going for real practical application: You’re a hiker on a trail in the forest, and right now there’s chanterelles up everywhere. And chanterelles are mycorrhizal fungi, so do chanterelles want to be found so we can spread their spores? Why are some mushrooms edible? Why are they so appealing to animals, not just humans, and how are animals involved in disperse of spores?

Merlin: Many mushrooms have definitely evolved to be eaten. Truffles are a great example, because they’re underground and there’s no other way for them to disperse their spores. They have to be eaten by an animal. With mushrooms, the spores can be spread through the air. But obviously the way that they’re colored, the way that they taste, the way that they smell, these are all characteristics that strongly suggest they have evolved to be part of animal lives.

So, yes. When walking in the forest and finding rich seams of chanterelles, just by picking these mushrooms, you’re helping to spread their spores. By carrying them around you’re helping to spread their spores. You can think of it as some kind of a co-evolutionary process, that we’re playing our part in the lives of these organisms by picking them and eating them—provided, of course, you don’t over pick them and overeat them.

These fungi have played such a key role in the evolution of plants on land in the first place: their evolutionary stories are completely entwined.

Paul: This really struck home to me, because I came across a very rare species of psilocybin mushrooms called psilocybe baeocystis—and psilocybe baeocystis is just very difficult to find. And I found them, as I walked from my house to my laboratories, in a straight line of about 300 feet. And the next year, I had a string of them, right on the path that I walked.

Psilocybe cyanescens was first discovered in England by a mycologist by the name of Wakefield. This is one of the most important psilocybin mushrooms in the world, and it’s curious, I’ve never found it in a native habitat, but one out of every, I would estimate, four truckloads of wood chips that have alder in them, psilocybe cyanescens just magically, literally, pops out of the wood chips, but I’ve never found it in an alder forest. So do you think psilocybe cyanescens is an endophytic fungus that just exists inside the trees, they get resistance to other pathogens and then when the trees are dying, get chipped up, they spontaneously come out? I mean, how do you explain why psilocybe cyanescens, which I’ve never found in the habitat, but when alder trees are chipped up, about every fourth load of wood chips, everybody, is magic mushrooms, in England—and Scotland—and France—in Germany—all across northwestern North America—these mushrooms just come out of the wood chips. How do you explain that?

Merlin: That’s a really good puzzle. I think the endophytic theory is a good one. Lots of fungi are endophytic, and then can spring out of the endophytic state into a decomposing state. And so that’s one possibility.

Paul: Well, then, by analogy of truffles getting discovered by animals, and humans are animals, they spread their spores, and if chanterelles benefit from humans picking them, and leaving trails of spores to new habitats, do you think that the occurrence of psilocybin mushrooms associated with human activities is somehow the species calling out to us, or trying to get our attention? What is the crosstalk between humans and psilocybin mushrooms?

Merlin: Certainly in modern times, there’s a huge amount of crosstalk. The evolutionary fate of the psilocybin mushrooms has transformed their evolutionary fate in the last 60 years. Many of them have been discovered in the last 60 years—as you know, you’ve discovered many of them. And now many people are learning to domesticate them, learning to grow them in their bedrooms, on their windowsills. And so their ability to influence our minds has transformed that evolutionary fate.

I do find it fascinating that so many psilocybin mushrooms have come onto the human map in a very short period of time. And especially these ones that follow us around, sprouting up in our messy wake. It’d be a beautiful irony that this mess and disturbance can produce fungi that might lead us out of that mess and disturbance.

Paul: If you were an organism and you opportunistically by chance, found another way of spreading yourself, genomically it’s in your best interest to capitalize on that sudden association and new discovery to say, “Hey, humans, I’m over here again. Come pick me up, because I want my progeny to be preserved and survive.” So I wonder if there’s a new bridge between mushrooms that are waking up as we are waking up, to engage us. And how do mushrooms tie us into a greater ecology of consciousness?

There is a world revolution in the interest of mushrooms right now. I’d like to hear your take: What’s the future of mycology?

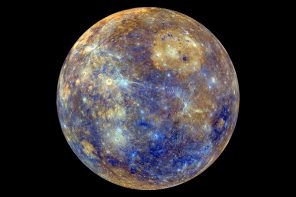

Merlin: It really feels like we’re at the very beginning of a new era of mycology. One of the reasons why there’s this explosion of interest is because we just know a lot more than we did, because we can investigate the fungal world in more detail using technologies like DNA sequencing or using isotopic labels, or quantum dots to track the movement of substances through fungal networks. And so I think this renewed interest is in part driven by technology extending our reach and opening up new investigative possibilities. There are other reasons too, of course, including the rise of network thinking and the many ways that fungi can help us adjust to life on a damaged planet.

Besides the many new fungal technologies and applications, I’m excited to find out more about basic fungal biology. All mycelial fungi are able to coordinate their behavior sprawled over potentially large distances, integrating information from all these data streams, without a brain to do so. We don’t really know how they’re communicating even with themselves. How much of this is electrical? How much of this is chemical, how much has to do with pressure, or flow or oscillations of chemicals? There’s a lot of very basic knowledge that once we find out, we’ll have a better idea of what they’re doing in ecosystems. I’m so excited to see what we find when we start asking these questions.