From the forest to the field.

The process of making a pro-model baseball bat may have evolved somewhat since Bud Hillerich made the first Louisville Sluggers for Major Leaguers in the 1880s, but one thing that hasn’t is how they start. Somewhere in a forest, near the center of a single maple, is a piece of wood with a dream of going to the Show. A lot of things have to happen for him to make it. That piece of wood is going to go through the hands of 45 different people and be graded no fewer than eight times. He can be cut from the team at any stage.

When it comes down to it, less than two percent of the trees out there make a pro-grade weighted bat and that’s where our expertise really has to come into play because we can’t cut down every tree to find that two percent, so we have to really learn about the wood.

–Bobby Hillerich, Director of Wood Bat Manufacturing, Louisville Slugger

A single wooden bat starts with its roots in the ground. Louisville Sluggers bound for the Show might be grown on a 50-mile-wide swath of land along the border of New York and Pennsylvania—60 acres of forest still owned and managed by the Hillerich family. The north-facing slopes of the range, the soil, the climate and shortness of the growing season (leading to tighter growth rings) produce maple, birch and ash with big-league stuff.

A single tree, which grows for 60 years, generally produces about 30 or 40 bats. But not all those bats will make it to the Major Leagues. Not even close. Only five or six, that come from the heart of the tree (where the rings are the tightest and the hardest) will ever have a shot at taking a swing at a fastball from the fingertips of Justin Verlander or Jacob DeGrom.

It’s been said that hitting a round ball with a round bat squarely is one of the most difficult feats in sport.

The timber is graded when it’s cut and then graded again six or seven times more when it gets to Louisville until the final step and the last inspection, so at each stop on his journey our Major League hopeful could be cut from the team. Wood that isn’t destined for MLB batters has a few options. Most is still high quality wood that goes onto years of loving use everywhere from youth leagues to college and increasingly, the Minors.

It’s been said that hitting a round ball with a round bat squarely is one of the most difficult feats in sport. The ball is 75mm in diameter and the batter has maybe a tenth of a second to see it and swing.

Baseball isn’t a game of feet or inches. It’s one of fractions of millimeters and hundredths of seconds and tenths of ounces.

A player might pick up a bat and like it, “but I want a slightly fatter barrel,” or “I want a slightly thinner barrel, and I want more end load,” or “I want more balance,” or “I want more of a taper between the handle and the barrel,” or “can you do anything with this knob?” You get the idea.

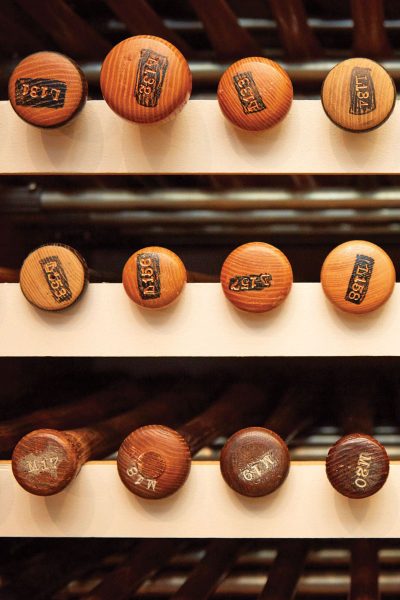

Before a piece of lumber becomes a bat, the bat-maker needs to know the shape. These minute variations and specs together are called turning models—which includes every dimension from knob to cup. The measurements are just that little bit different, whether the knob shape, handle thickness, taper, or barrel. Every new and distinct bat that’s ever been made by Louisville Slugger in its 130-plus years is a new and distinct turning model. And each of those models is coded with a number that corresponds to the player it was first made for using their last initial. There are about 5,000 such models in the Slugger catalog.

Jackie Robinson swung an R17, a turning model made to his specifications and named for his last initial and the fact that he must have been the 17th player whose last name started with an R to have a model made for them.

At this stage, we have something that looks like a bat in our hands, but is an unfinished piece of wood. It’s not just a logo, player’s signature and cool-but-ultimately-meaningless “Powerized” mark that makes that naked wood a Louisville Slugger destined for home plate at Yankee Stadium.

The treatment process has anachronistic names like “bone-rubbing” that come into play, ones that might trace their history back to the early days of bat making but are where technology makes a difference. Bone-rubbing was a traditional bat hardening method where the barrel is literally rubbed with a cow femur to close the grain. Some players still do this in the clubhouse to their bats to this day, though it is unnecessary (these are the same guys though who probably wear the same pair of tattered underwear for weeks straight if they are on a hitting streak). The cow bones and superstitions have given way a bit to technology, with a proprietary machine that puts a great deal of consistent pressure on the barrel all the way around to close the grain a bit more scientifically than rubbing it with a cow femur.

The finish has a direct correlation to hardness. So for this bat—with all its pedigree—to go to the Show, he’s going to get a top-notch finish, just like the bush-league basher who needs to work the kinks out his swing if he’s ever going to make it out of the Grapefruit League.

Applying new techniques and technologies to bat finishing has kept Louisville Slugger at the top of the standings. One of its latest finishes came out of a meeting Bobby Hillerich had with Taylor Guitars after he got interested in the application they used for the beautiful and durable finish on their $5,000-guitars—modified for baseball, of course. “Typically, Taylor doesn’t take their guitars and smack it at 200 miles an hour against a three-inch sphere,” points out Hillerich.

The EXOPRO finish might just be the biggest advance in this process in the company’s 135-year history. Something players say you can touch in the sheen and see in the way ball threads don’t dent the barrel the way they might and feel in the way the ball comes off the bat.

Now the Slugger is ready for the Big Leagues.

Know Your Wood

Maple

Maple

The hardest of the bunch, thanks to a very dense cell structure and produces a most satisfying and recognizable crack when the ball hits it. About 80-percent of Major Leaguers swing maple.

Ash

Ash

Almost as hard as maple, but with a little bit of flexibility to it, a little whip. Maybe think of a golf club.

Birch

Birch

A hybrid in some ways of maple and ash. It has a very similar cell structure to maple, very dense, very tight, but it has a little bit of the whip that ash has, not quite as much. And makes a bit of a different sound on contact.

The History of the Baseball Bat

1850s

At the start of organized baseball with games played using Alexander Cartwright rules (9-inning game, 9 players on each team and 3 outs per side) there were basically no rules as to what a bat could be and players made their own. Some of them showing up to the game with square 42-inch, 60-oz clubs.

1859

By now, round-barreled bats had become most popular, but the size was anything but standard. Players scrambled to woodworkers to reshape their bats when the Professional National Association of Baseball Players Governing Committee voted that the barrel be no larger than 2 1/2 inches.

1860s

And after experimenting with just about any kind of wood they could get their hands on—maple, willow and pine were common, but also spruce, cherry, chestnut and sycamore—players gravitate toward ash, which becomes standard.

1869

Major League Baseball is founded and with it, a regulation limiting their length and bats became basically what we’d recognize today: a smooth, round stick not more than 2.61 inches in diameter at the thickest part and no more than 42 inches in length made from a single piece of solid wood.

1884

Seventeen-year-old John “Bud” Hillerich plays hooky from his Dad’s woodworking shop in Louisville to take in a Louisville Eclipse game. After the team’s slumping star Pete Browning, known as “The Louisville Slugger,” breaks his bat, Bud offers to make him a new one. He does and Browning goes on a tear. Soon others are requesting the “Lousiville Slugger” bat from Hillerich. Bud’s dad is more interested in making stair banisters.

1894

Bud Hillerich patents the Louisville Slugger name and takes over his dad’s business.

1905

Honus Wagner becomes the first sports star with an endorsement deal, putting his name on a Louisville Slugger bat.

1923

Louisville Slugger becomes the country’s top manufacturer of baseball bats and has been pretty synonymous with them ever since.

1999

Office Space is released, forever changing how we look at the relationship between printers and wood baseball bats.

2001

Barry Bonds hits 73 home runs using a maple bat. And because there can be no other possible reason for his sudden and stunning success, players begin requesting maple bats, and ash, which has ruled since the 1860s, quickly goes out of vogue.