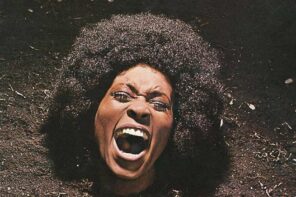

Whalebone sits down with musician and winemaker, Maynard James Keenan

Maynard James Keenan is willing to take some risks for the things he loves. Fortunately for those who believe in locally sourced and grown produce and grapes, Maynard, loves them both very much. Whalebone Magazine sat down with the Arizona winemaker to learn about how not to confuse patience with complacency, why the soil in Arizona is better than you think, and how to possibly re-wire humans.

A casual conversation with a renaissance man who has performed for millions around the world as the lead singer and founder of the band Tool and now spends most of his days making sure his growing world-class wine operation is going well.

Whalebone: Arizona might not be the first state you think of when it comes to wine— what’s the best thing about wines from Arizona that somebody might not suspect.

Maynard James Keenan: I think one of the missing pieces for people’s understanding about Arizona, they just assume that it’s all desert. But actually, there’s an extremely large agricultural element to Arizona. There are so many things that grow here. Pecans, pistachios, grapes. There’s a lot of orchards here—a lot of fruit trees, olive trees. There was a wine industry back in the early 1900s before prohibition. It is a climate that can grow anything that grows in that Mediterranean belt across Portugal, Spain, Southern Rome, Italy. It grows here.

WB: How important is the local community in Arizona and in your neighborhood in shaping the mindset and end product of a winemaker? And that could be for you or for any winemaker.

MJK: I think as far as commitment to community, you could put in corn, you could put in alfalfa, it’s going to grow that year. And if you decide that didn’t work out, you can just pack up and leave because you’ll know the product is going to go within the first one or two years. With wine, with vines, you’re making at least an eight-year commitment just to start without having any evidence in front of you. You plant a vine, it takes four years to grow to the point where it’s producing fruit, takes another four to eight years for it to really show what that system is capable of in terms of its fruit. So you’re talking about an eight to twelve-year commitment.

If you plant a thing and you’re there to watch it grow and nurture it and bring it up and you haven’t done that before in your life, it changes you. It re-wires you.

And then if it’s successful, you have a lot of industries that can hang their hat on that success. All the collateral, all the peripheral industries are going along with that. Hospitality, food and beverage, more agriculture, accounting. Just every little thing you can think of supporting industries like mechanical. So there’s quite a bit that ends up being in an area that can hang its hat on that commitment.

WB: Do you feel that there needs to be concept buy-in from any local community for a new winery? Or is there somebody who’s taking it on that wasn’t generational? Or do you think it’s inherent that, “Oh, that’s what the land produces, we’ll support that.”?

MJK: There’s pushback on pretty much every startup area that’s tried their hand at it. It’s almost like a broken record, Groundhog Day, with the stories that come along with it. You’re starting to build a wine industry, the laws aren’t in place to actually accommodate it so they try to stop what you’re doing because the laws don’t fit it. When in fact that the law should be changed to accommodate what you’re doing because it’s been successful in other states and it’s even more successful when the state buys in which usually takes 10 to 20 years.

WB: A lot of patience, So congrats on that so far. Wine and music are great, but getting outside your comfort zone, is there anything interesting you for the future, it could be wine-related, but perhaps not, that people might be surprised by, including yourself? That could be another industry or another sport, whatever it might be.

MJK: Yeah. I think some of the things I mentioned, some of those just as collateral activities, I think people start finding a connection to the process. They started finding a connection to just farming in general and see how it doesn’t have to be this elusive, crazy thing that’s unattainable. Just having planter boxes outside your back window, you start to see that as being achievable once you’ve touched these things, because, let’s be honest, if you plant a thing and you’re there to watch it grow and nurture it and bring it up and you haven’t done that before in your life, it changes you. It re-wires you.

And the other collateral—what’s wonderful is that with all these industries I mentioned, most people when you have the conversation about a piece of equipment, a trucking agreement, buying beverages and things for your tasting room, just everything you could think of down the line, that people tend to put aside the politics, religion, all that shit starts to go by the wayside to have this conversation person to person. That connection between people. And they start to see more of the similarities than the differences.

WB: Yes, so well said. I hope people can take more of that from all this. It seems that wine and good food lead to conversation and that transcends those boundaries, which then leads people to drop their, I guess we’ll call them preferences, through these connections. In your experience, how could that be better communicated to the world for somebody who has probably not seen a plant grow? How could the wine industry communicate that in a better way?

MJK: Honestly, I don’t know. I would love it if I could figure out that magic word or that magic phrase, I would definitely use it over and over again. But I think it’s kind of like that biblical story of Moses coming down from the mountaintop and having seen something incredible and there’s no fucking way you can put that into words to have somebody experience it the same way you experienced it without them having experienced it themselves. In some cases they have to learn from their own experiences, otherwise, it won’t resonate with them.

WB: Is there a favorite bottle or a meal that you’ve ever produced?

MJK: Well, I think it’s more those baby steps of us planting something like a Nebbiolo and having everybody go, “What the fuck is wrong with you? You’re really going to try to plant Nebbiolo and Barbera and Sagrantino and expect that to go well?” And when it goes well. And you did the right thing and it worked out. So not necessarily a favorite specific bottle, but just a favorite moment where you put those wines in front of somebody. We did it with our Tempranillos, Spanish grape.

Once, we had some wine writers that were in town. We’re just trying to figure out our lineup, which years are shining over other years, which blocks are shining over the blocks. And we lined up a bunch of Tempranillos, blind, for these experts to look at. And they jotted down, “This one seems like it’s a little past its prime. This one shined for sure. This is my favorite.”

And, not scores, but ordered them—number one down to number eight, here’s what we liked in that order. And then I pull off the paper bags and four of the wines in the lineup, actually three of the wines in the lineup, were world-class Spanish Tempranillos from Vega Sicilia. In fact, a Unico, their Reserva label, also Vega Sicilia Unicos of various years. And those were not the top three.

Our wine sat right in the middle of all these world-class Tempranillos. I’m not tooting my horn, “Hey, we’re making wines as good as Vega Sicilia.” What I’m saying is that in context, blind context, putting it next to what’s been considered successful in the world, in many ways, unicorn wines, we did okay. We didn’t come in last. So those moments are the moments that make your heart race.

WB: Yeah. And congratulations to you and the whole team that got behind that. That’s a great feeling.

MJK: But the risk, your balls are exposed. If that didn’t go well, you know?

WB: So the second part of this question— is there a favorite show or crowd you’ve ever played for or something you’ve ever done on stage that’s your favorite? And then the end part of this is, which one of those would win?

MJK: I don’t know if you’ve spoken to a lot of successful musicians before, but I would imagine most of them have been successful in one particular band. And at some point I think, and I’m no mathematician, but I would imagine most people that are in very successful bands, there comes a point, there’s a statistic that would support this, that they get a little lazy and complacent. They confuse patience with complacence and they’re not really trying to challenge themselves.

I think my favorite moments have been when I’ve started something new with another group of people, and actually pulled off a cool thing or a cool show that went better than we expected. So in both, I think that the calculated risk that you mentioned is the common factor. Yes, you’ve been successful with that thing, but really starting over, getting back into the van and trying to see if you can duplicate that kind of success but in a completely different way, with a completely different grape, with a completely different band, and still end up nailing it, or coming close to nailing it. So I don’t know that I could pick one or the other as far as that.

But I think if you really dive into this world, your tastes are going to change and eventually you’re going to like more of those subtle, elegant Pink Floyd wines

WB: Three wines you would recommend to anyone reading this publication. Just three wines.

MJK: I think we have to almost qualify it a little bit first. This is always the dilemma in anybody’s tasting room, or even in a bottle shop. What shines for you, doesn’t shine for somebody else. But as far as context and perspective, I love putting something large on the table, like an Argentinian Malbec or an Australian Shiraz or a California Cab, or a California Shiraz. Picking one of those, it’s the shining thing. Looks good on the table.

In the middle, put something that’s just generally considered to be gorgeous, not huge, but just kind of gorgeous, like a Nebbiolo or like a bar Barbaresco or Barolo, put that on the table.

And then just for pure perspective, something like, and this might lose a lot of people, Lacrima di Morro d’Alba, which is an Italian wine grape. There’s no real structure to it. There’s no body to it. The aromatics and the glass are so stunning and so beautiful like rose pedals. Just all these glorious, floral things happening in the glass that it’s just an experience. You get to understand those aromas. It’s not going to drink like a California Cab. So you have to go in that order, you have to go with the lightest to the heaviest.

Nine times out of ten, first-time drinkers, if they’re used to growing up eating Golden Grahams and drinking Pepsi and Coke, they’re going to like the big one first. But I think if you really dive into this world, your tastes are going to change and eventually you’re going to like more of those subtle, elegant Pink Floyd wines, rather than the Metallica wines.

WB: What’s Something that wine has taught you, that music could not.

MJK: Wow. Think about that one. Something that I’ve learned more with wine—I think it was that respect. And that’s something that I had learned as a kid growing up in the middle of an orchard and working in the peach and apple orchards and my father having his own vegetable garden and working the farms. And I think you lose touch with it as you get older and you move away. With bands, they don’t really seem to have their finger on the pulse of stuff that’s out of their control, like weather, just mother nature in general. I can write a song whether it’s raining or whether it’s sunny or I can just dig in and do my thing. But with farming, you are absolutely not in charge. There’s only so much you can do to guide that grape in the bottle. Just get off that vine at the right moment. And you’re absolutely a slave to the weather. So I think patience really isn’t the word, I think, it’s just respect for things that are not in your control.

WB: Can you tell us a little bit more about what’s coming up for the future of your projects out there or what you might like someone to know about?

MJK: I have two facilities. One is the actual co-op facility with a couple of other wineries that work under our roof. And then, of course, there’s the bunker where I make most of the Caduceus wines. That’s where I was today. We just processed about 15 tons today. We’re building another facility in Old Town Cottonwood, Arizona, up on the hill. It’s just under an eight-acre site, that’ll have four acres of lines right on site. The Caduceus facility will be moved from our other location up to that hill. And we have an osteria that’s in Old Town Cottonwood, that line should be moving up on top of that hill as well. That will change the name to Merkin Vineyards Hilltop Trattoria. And that should be opening, knock wood, by the fall of ’22.