Gender, Drugs, Drums, More Drugs, and Rock’n’Roll Camp for Girls

Patty Schemel has the dubious distinction of being kicked out of the band Hole for doing too many drugs. When Courtney Love is planning your intervention you know something is amiss—Schemel’s reaction to that approach as recounted in her memoir Hit So Hard was, “Really? Because this worked so well when you pulled it with Kurt.”

Years before it had been Kurt who first suggested Schemel to Courtney when Hole needed a drummer, and the pair are entwined with the story of Schemel tells about the early days of the Seattle music scene. But the book, a further exploration after the documentary of the same name, is much more than a drummer’s eye view of that era. Schemel starts at the beginning from being a young girl, feeling awkward and out of place to finding the drums, which as a preteen she played until her hands bled.

The third act of the book is devoted to Schemel’s recovery and relapse and then again recovery, which provided some her biggest motivation for sharing her story. We reached her at home in Los Angeles to talk about Garanamals, narcotics travelogs, the Rock’n’Roll Camp for Girls (which is a real thing that actually exists).

Lived Through This

WB: What was the process of writing the book?

PS: A few years ago a friend of mine was looking for some video footage of our friend Christine who passed away. And I had a lot of Hi8 stuff still on tape. She is a filmmaker and she said you should preserve that stuff. Digitize it. In the process of going through all of the footage my wife, who’s a producer and filmmaker, was looking at all of the footage while we were digitizing it and she said, “You should do something with this. There is some good stuff.”

When I toured with the documentary, there was a lot of conversation after each screening about the recovery part of my story and also interest in that time in music and in Seattle. I was approached by a publisher. I’m not a writer—well then I wasn’t. And so, he introduced me to Ellen Hosier who helped me sort through the memoir. The idea was to tell my story in more detail. And I wanted to write a lot about the recovery part a little bit deeper.

It started out as her asking me questions. So like an interview over the phone. When she started to send me pages, I was feeling like my voice wasn’t in it. And so, we sort of changed our process to Google Doc, which we both wrote from. She’d write at the top, “Tell me about this?” And then I would write pages. Just sort of really punk rock about it with no rules and I’d just write about whatever the topic was. That’s how it started. And then I would go away for a while. I’d leave town to just go focus on doing the writing—get out of town and just turn everything off and go back into the time of scene.

It was really weird to emerge from one of those lessons of just writing and then get back to the present day life. I thought that I was maybe further along with dealing with a lot of the sadness, those harder parts of the story, than I really was. Like it would have been nice to share my life today with Christine. I didn’t really think I would feel that intense about it again.

WB: The book starts with you growing up in the ’70s and early ’80s, recounting those things that really anyone who felt like an alien at school might relate to. At one point you bring up Garanimals. What did those clothes mean to you?

PS: My mom was dressing me back then and it was about I didn’t want to wear the dresses that my sister was wearing. And when Garanimals came along, I don’t know. That way, I could put together my own outfit by just matching the tags. I’m going to wear these. This is an outfit that has pants and not a dress.

The pop culture of the ’70s raised me. I grew up with the TV as my parent pretty much. When my parents were divorced, there was no one there. That was the world I lived and wanted to part of. Because we were so way out at the time, it was the Pacific Northwest … We were way behind. We barely got cable in 1983 or ’84 or whatever. So, when Saturday Night Live was on, that was sort of my looking glass to everything cool like, oh, my god, seeing Patti Smith or seeing the B-52’s and David Bowie.

WB: And pre-internet that’s like–

PS: Huge. And life changing. Discovering punk rock through the TV and then discovering it through a small radio station in Canada that I could get on my boombox. Just hearing music the way that it was always delivered through the radio on the top 40 stations or the rock stations and then hearing this crazy sound coming out of the speakers or on my headphones. It was so cool and scary and different. I felt really connected to the discovery and that no one else knew about it and that it spoke to me personally. I eventually saw more women playing music in punk rock and heard more women’s voices. Women weren’t dressed provocatively. There were screaming and playing.

WB: And where were you seeing them?

PS: When I started going to clubs in Seattle and started going to punk rock shows.

I felt that I was being heard, literally because it was loud.

WB: Prior to that when you picked up the drums what appealed to you about them when you were 13 years old?

PS: I felt really always kind of weird and different anyway because I was gay. I chose drums because it wasn’t something could be enforced like sports were. Girls can’t play that and they can’t do that. And I was drawn to music, and drums were the thing I wanted to do, because I didn’t see a lot of girls doing it. And it was physical, and it was loud. I felt that I was being heard, literally because it was loud. When I started playing, I started to feel all of sudden like I had arrived inside my body. I was there. Later on, that was what alcohol did for me too, that same sort of, “Okay. Now, I’m here on earth and feel comfortable where I am.”

WB: Did you have any kind of musical role model or people that you looked up to or wanted to play like or sound like?

PS: As a kid in the ’70s—a lot of people don’t get it—but I really liked Kiss. They were huge for me as a kid. When I started listening to punk rock, I really liked Budgie from Siouxsie and the Banshees. I liked Ringo Starr and I liked John Bonham. And then Gina Shock of course. And Sandy West from the Runaways.

WB: Later on you talk about listening to Spaceman 3 and Galaxie 500 and bands like that. Did you aspire to that kind of that sound at any point?

PS: Yeah, I did. And I wanted to be in those bands totally. When [my brother] Larry and I did Cybil together in ’91, we wanted to be Spaceman 3, we wanted to be Galaxie 500. It had that sound. In Seattle, they were a little more rock I think. But I wanted to be, and I still do, I still love that music and I still want to be in a space rock band—noisy but melodic. Like My Bloody Valentine.

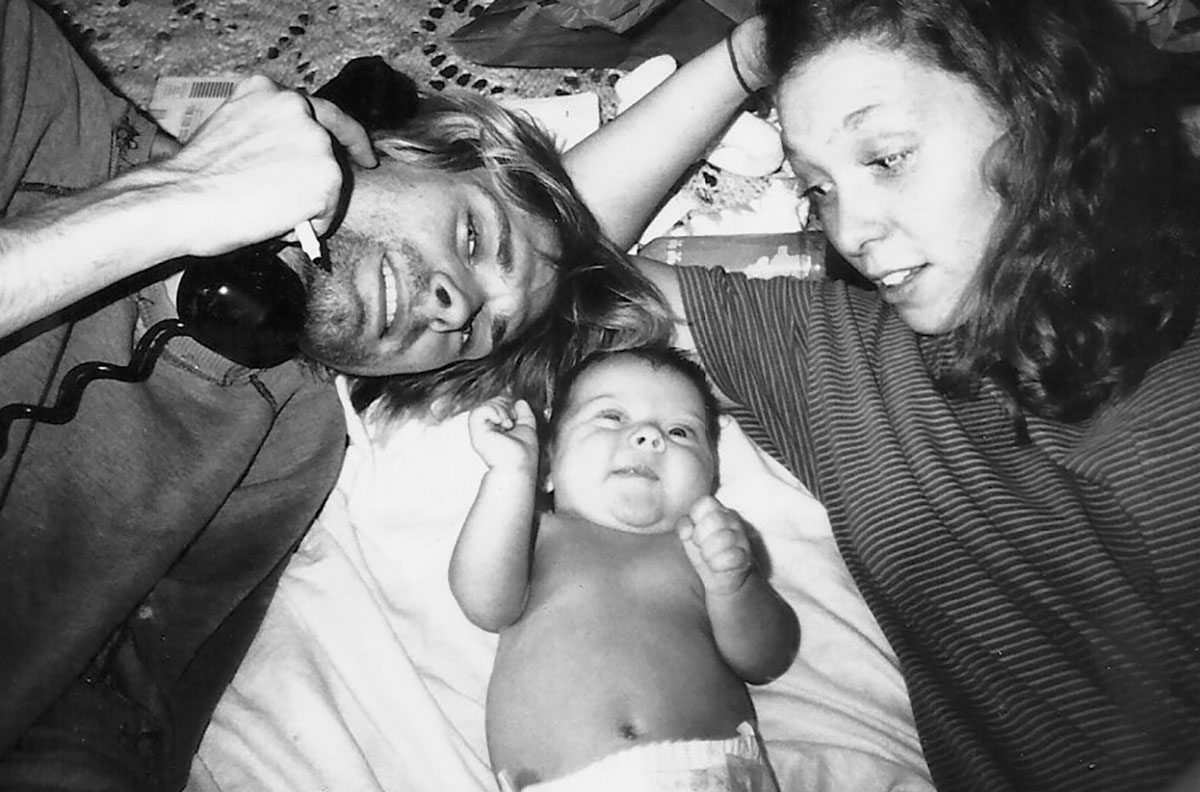

Kurt, Frances Bean, Patty. Courtesy Patty Schemel.

Runaway Runway Grunge

WB: In the book it’s funny, everything in Seattle happens really fast—all of a sudden everybody is really famous, all your friends and everybody you know is really famous. Did it seem like it was that quick?

PS: Yeah. It was like that. All of a sudden Seattle, which was not a place of note at all, becomes huge and everybody who was in a band was moving there. People moved there from like Arizona and Idaho.They moved there and started living there to get signed. Really any band was getting signed, it didn’t matter.

I didn’t expect it to go as worldwide like that. After a while, it became a joke. And then there is a grunge wear on the runway. It became really a cartoon.

WB: What band should have gotten more attention that didn’t?

PS: Mudhoney for sure. They should be huge, they don’t want to be though. They were like the originators, the creators.

It became really a cartoon.

WB: Do you think there was a negative aspect to that happening so quickly or it’s just how it happened?

PS: In a way, just really any band that showed up—then it really gets watered down after a while. I’m just going to say it—then fucking Candlebox shows up. And then you’re like, “Okay.” Sorry, Candlebox but…

Hole. Courtesy Patty Schemel.

WB: You start drumming with Hole then you all end up in LA. Hole for all intents and purposes becomes more of an LA band?

PS: It was always an LA band, really. Eric [Erlandson] and Courtney are from LA and that’s where they started it. And they put out like one Sub Pop single, but they weren’t really a Seattle band. And they did a tour with Mudhoney. Courtney always knew that Seattle was cool, before the rest of the world knew it. And so, putting out a single on Sub Pop was part of her plan. And then a Mudhoney tour. So, yeah. They were originally from LA and we all started looking for a bass player, me and Eric and Courtney in LA, living down here.

WB: What’s the legacy of your work in Hole? And what are you proudest of?

PS: And I think that the work I did as a drummer—as a female that was a visible and out lesbian and talking about it. I’m proud of that because I remember the person I was as a kid, I felt awkward. I feel like it helps the kids that feel awkward to know that. A lot of kids say, “I saw you playing, I started playing drums because I saw you.” Or, “I came out after you came out in Rolling Stone.” I’m proud of that and I’m also proud of the recovery part of my story that it was so hopeless at one point. I never thought I would make it out. Part of [my] being a part of the world today is about talking about recovery and sharing that and listening to other people that need to be listened to.

And my hassle was so shitty.

WB: In some sections, the book is almost like narcotics travelog with “How to buy drugs in New York,” “Buying drugs in LA.”

PS: Yeah. The grind of it. And my hassle was so shitty. I was never the functioning addict; I was never Lou Reed or Jim Carroll at all. And I wanted to make sure that that is conveyed. That I didn’t romanticize it. It wasn’t cool, and it wasn’t pretty like the whole skinny model runway ’90s grunge thing. It wasn’t that—it was hand jobs for five bucks and maybe some crack. Oh, God.

Waiting for Kathleen Hanna

WB: There have been all of these stories about the sexual misconduct and harassment going through Hollywood and DC and wherever else. There hasn’t been that much in the music industry. Is music kind of on deck?

PS: I mean there are a few things coming out in music. And that sort of me to says what the fuck did we do? In the 90s, there was such a push for feminism and we were so out and loud and making sure that there were safe spaces for women in music, and we need that again.

WB: That didn’t sustain.

PS: Yes. And why not? What happened? It just sort of turned on its head and then we got Limp Bizkit. It’s that.

In the ’90s, there was such a push for feminism and we were so out and loud and making sure that there were safe spaces for women in music.

Because we were accepting of it, and sort of not accepting it. But that’s the thing, I’m waiting for, this is horrible, but I’m sitting here waiting for Kathleen Hanna to step in and take control of everything and go, “Okay. Here we go.” I can’t wait for her, I’ve got to do something now.

I think where things start is in programs like Rock’n’Roll Camp for Girls.We’re giving girls the tools and we’re telling them what’s okay and what’s not and how to recognize when you’re being talked down to or just treated like a minority. That’s where I put my effort.

WB: Is that something you’re very involved in?

PS: Yeah. What it is it’s a camp for girls 8 to 18. They go in, and they learn how to play an instrument, start a band, write a song, and then they do show at the end of the week. And it’s non-profit. It’s not so much about learning how to play an instrument professionally, but it’s about giving them the tools to express themselves. It’s about building self-esteem. I look back on my time as a beginning drummer and think about the times I walked into the drum shop and was totally ignored or talked down to.

What we do at camp, when I have drummers, is explain all parts of what it’s like to play and what parts of the drum are. I break it down so that when they go into a store they know what they’re talking about and don’t have to feel overwhelmed or mansplained to. And being a visible and outspoken female musician, these things are the things that I do today to tend to—it might be corny sort of analogy—that garden of feminism we started in the ’90s music scene.

Okay. The revolution starts with us and we’re going to start with this.

WB: There has been no continuum, that there was that wave through the 90s, and then it just kind of crested. And it’s an oversimplification to make it just about sexual harassment but it’s more so about the gender imbalance. Maybe it’s more pronounced in music. Do you see a way that what’s in the news and culture now starts improving the situation? Since there’s been this awareness now are we primed for that wave to come back?

PS: Some days I’m really depressed about it and some days I’m not. My take on it right now is that—and it kind of gives me some hope—is that with the events coming out, about all this sexual inappropriateness, that the women were like, “Okay. The revolution starts with us and we’re going to start with this.” That’s my dream and wish, that women are starting the revolution right now and we’re starting there.