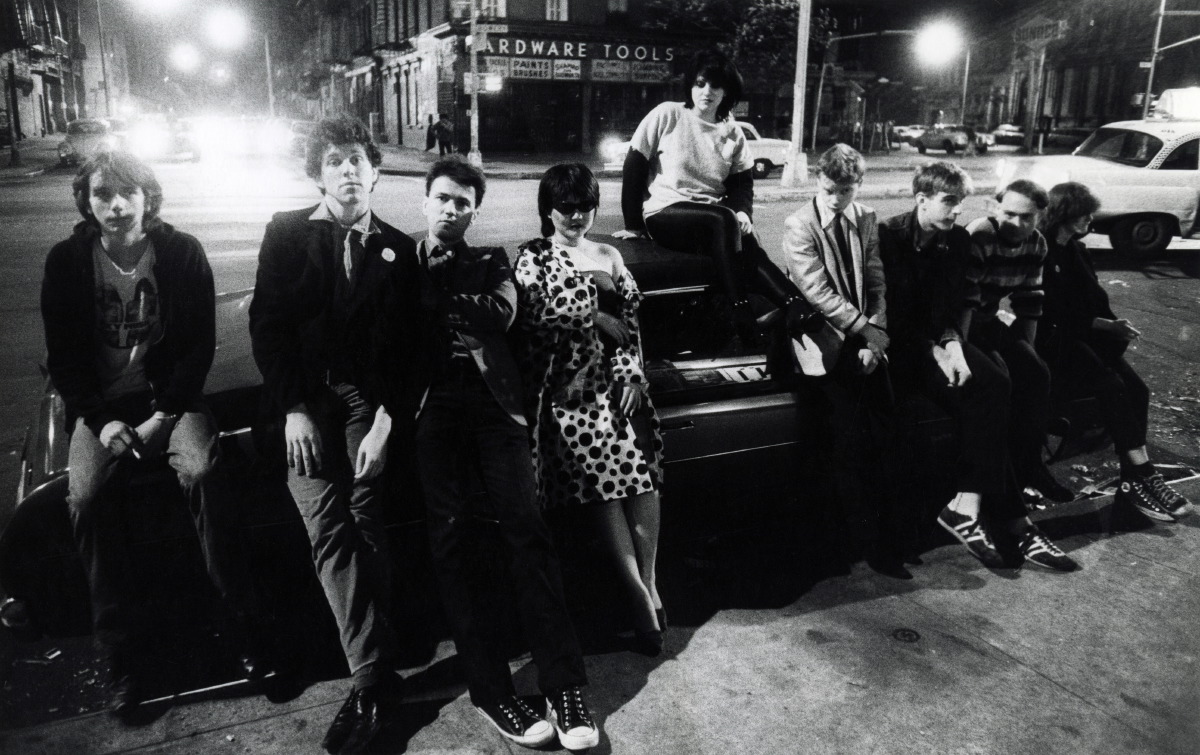

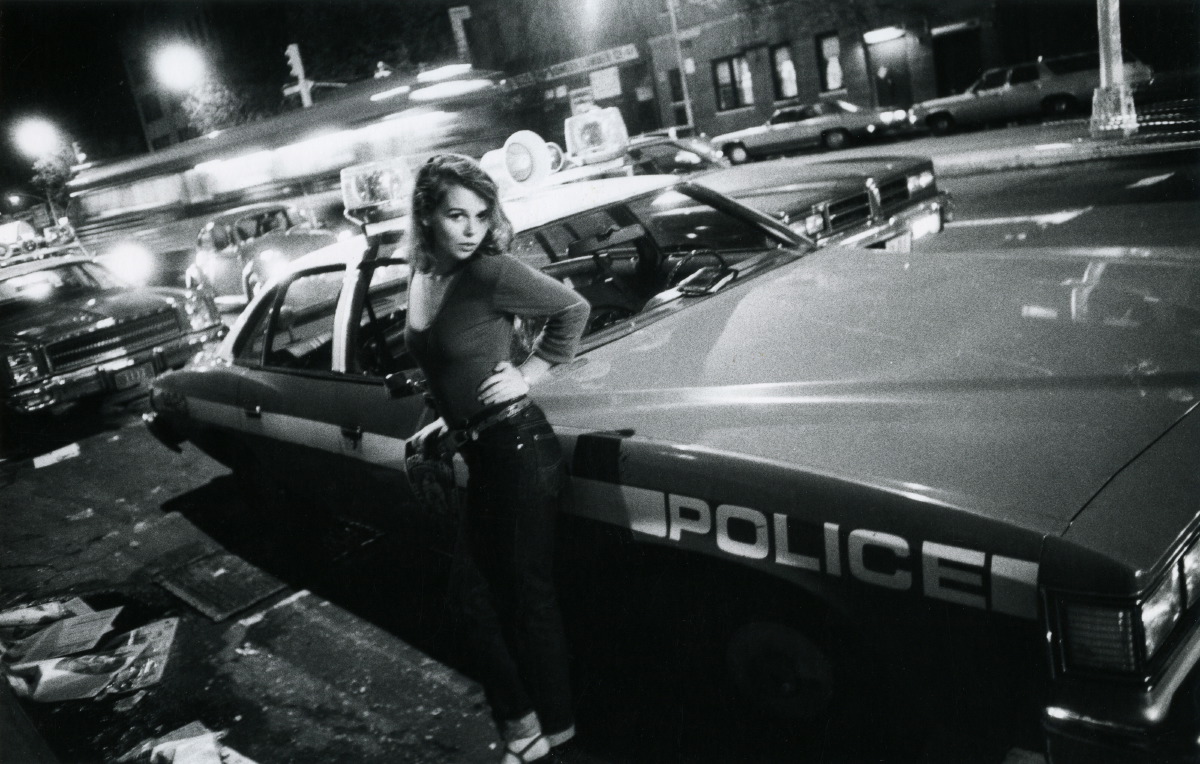

Talking with photographer GODLIS about taking pictures of the Lower East Side at night in the ’70s.

David Godlis came to New York City in 1976 to shoot photographs. And, for a couple of years, he found his subjects along the Bowery in the artists, musicians, poets, writers, filmmakers and, as frequent subject of his shots Patti Smith put it, “just kids” who hung out there and haunted CBGB. He had an aversion to flash, wanting to capture the truth of a moment in his images. He experimented with chemicals in the darkroom to make the most of the light in the dark the Leica collected on the black and white film and held his hands very, very, very still. The era is documented in his book, “History is Made at Night.”

The worse the city looked, the better it was for my pictures.

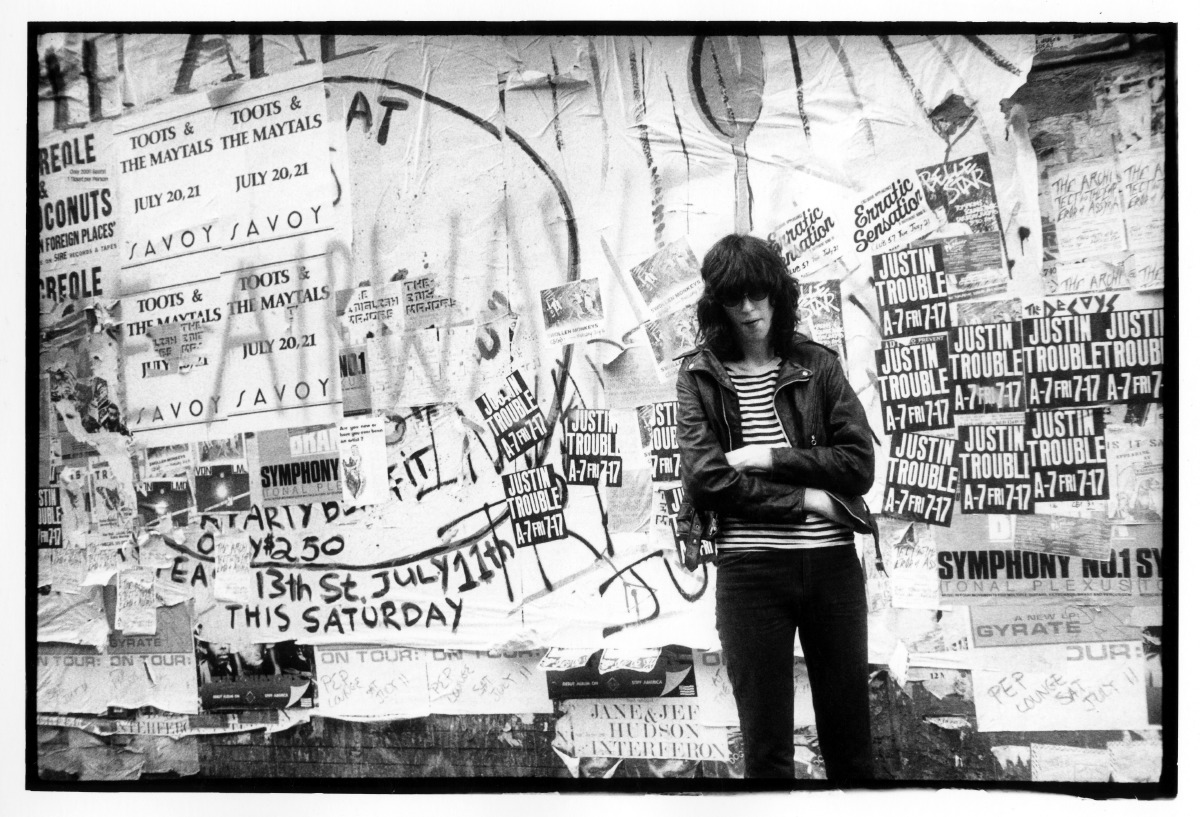

Danielle, Bowery 1977. © GODLIS

When was the last time you remember the LES being dangerous?

GODLIS: My first thought is not for quite a while. I walk around my neighborhood on St.Marks a lot without ever thinking about it. But on second thought, I realized that only a couple of years ago, my neighbor’s dog was viciously killed right outside our door by a pit bull, owned by one of those crusty kids that hang around the streets of the Lower East Side. It’s New York City, and you never know. Pay attention and stop looking at your phones.

A time you wished you’d had a camera but didn’t?

GODLIS: I always carry my camera. Even to the supermarket and laundromat. If I don’t carry it, I’m sure to see something I want to photograph. It just works out that way.

Anyway, the one notable time I forgot to take my camera with me was years ago on my daughter’s third day of school when she was in third grade. I was about to go back upstairs for it, but she said she didn’t want to be late, and so I let it be. Well, after dropping her off to school that day near Chambers Street, over my head went the first plane into the World Trade Center. I might have gotten a shot of the plane going over my head. But I also likely would have kept shooting pictures and gotten buried in the rubble. Instead, I went straight back to pick up my daughter from school and get the hell out of the neighborhood. No camera, no distraction that day.

But honestly, if I go out without my camera, I will always see things I want to photograph. It doesn’t have to be as dramatic as 9/11. But I’ll see something. So I always carry it with me—even while doing my laundry.

But I also likely would have kept shooting pictures and gotten buried in the rubble.

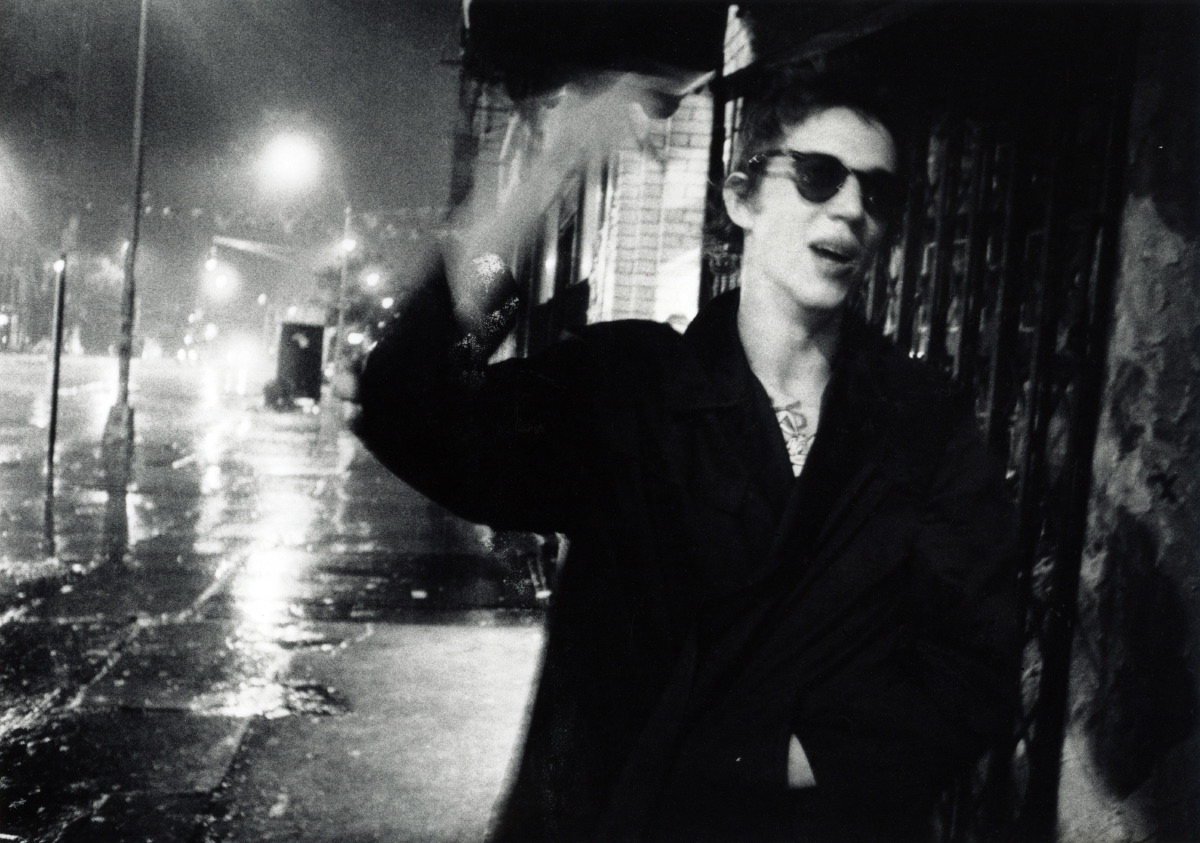

What were your usual hours during the era depicted in “History is Made at Night?”

GODLIS: I had a 9-to-5 day job as a photographer’s assistant at the time. So out at 7 a.m. I’d come home at 6, relax a bit, have a slice of pizza, and go out to CBGBs for the night around 8:30 to 9 p.m. I’d be out there till at least 2 in the morning. Sometimes 4 in the morning. Say goodbye to everyone there. Eventually get back home to sleep, and off to work in the morning. Then say goodbye to everyone at work, and start all over again. I did that for about three years. Eventually, the hours of sleep got shorter and shorter and started taking a toll on me. Around this time, when I was starting to walk around with very little sleep, I remember photographing The Cramps. I might have been acting a bit strange, and I remember thinking that they all thought I was crazy. When The Cramps think you’re crazy, it’s time to start getting more sleep. So I did.

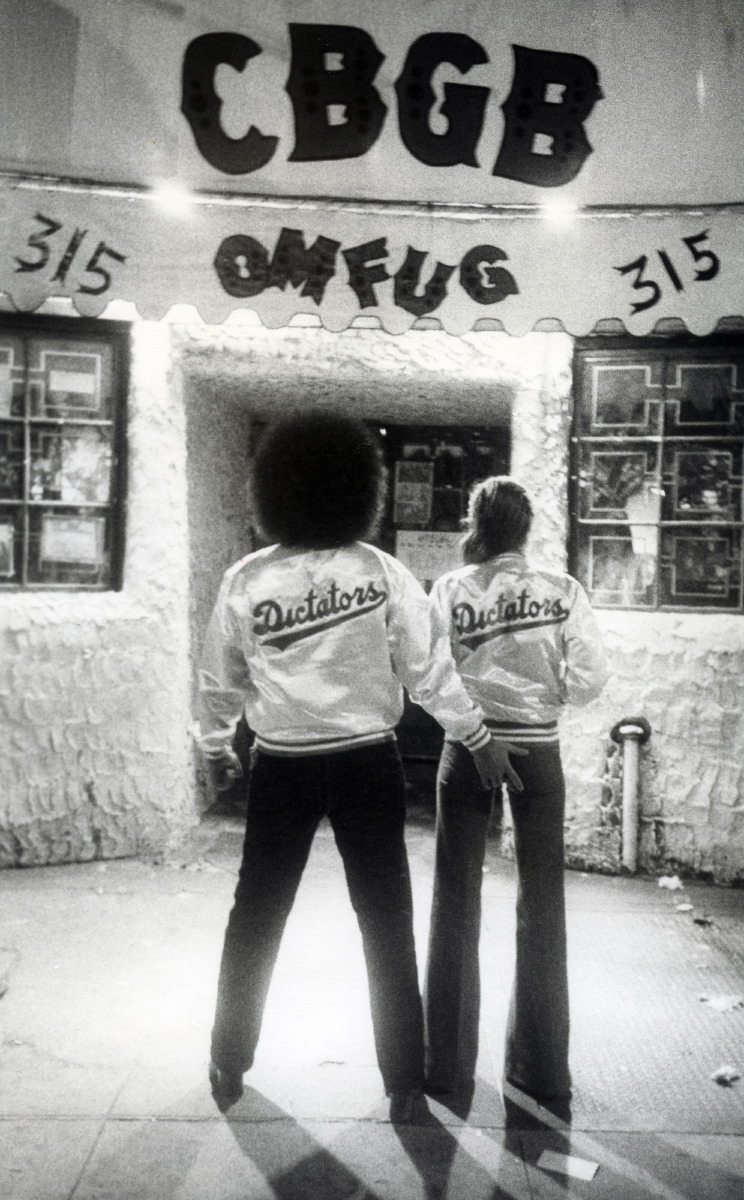

Television was the first band you shot at CBGB; who was the last?

GODLIS: I think it was The Revelons. That would have been October 2006. It was just before that last week at CBs that I left to go to Japan for an exhibition. I was actually with a group of other punk photographers—Roberta Bayley, Marcia Resnick, Leee Childers, Danny Fields. It was an exhibit—”Bande A Part”—at Agnes b.’s Gallery in Tokyo. The only one of us who made it home in time for the closing night at CBGB was Danny Fields. Roberta Bayley (who was the original front desk girl at CBGBs) and I listened to the closing show on the computer at 9 in the morning in Tokyo (12-hour time difference). Roberta said it was the best way to experience it—over coffee in the morning.

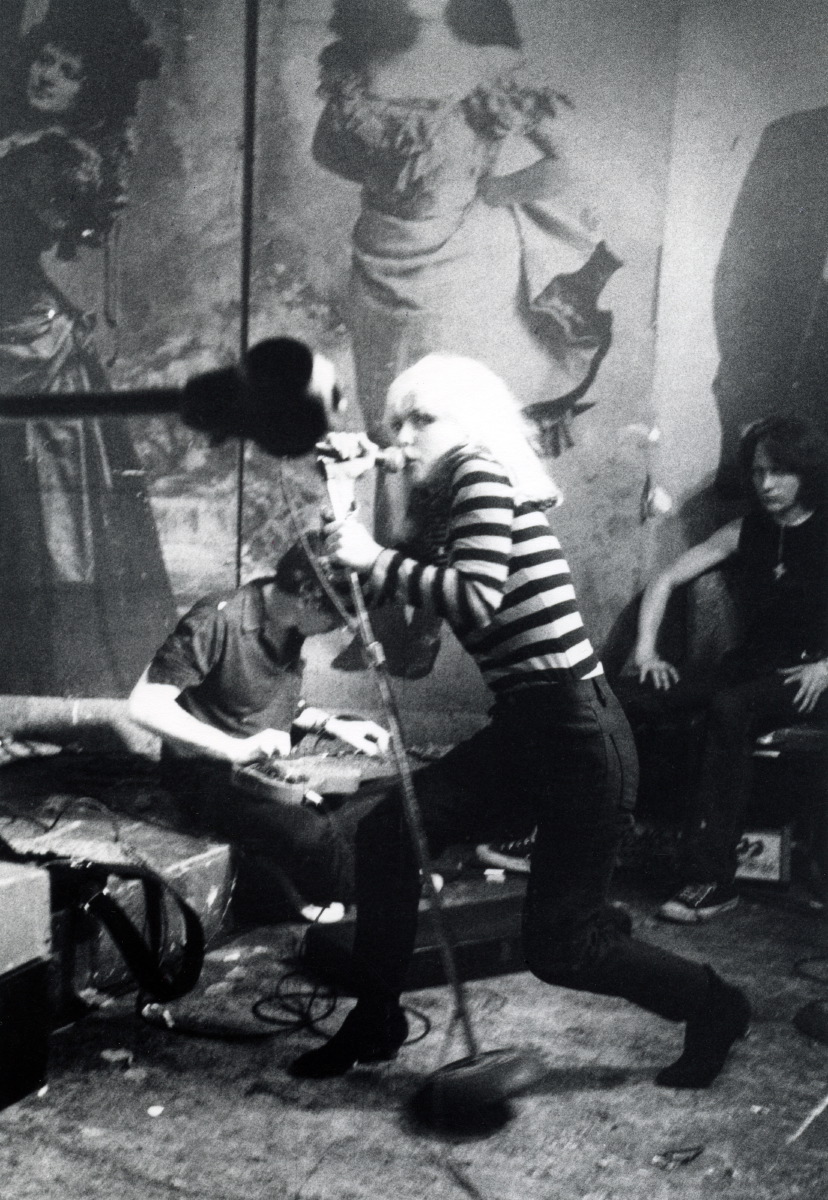

When The Cramps think you’re crazy, it’s time to start getting more sleep.

The Cramps, Bowery 1977. © GODLIS

What should we know about shooting on film with a Leica in the dark without a flash?

GODLIS: Breathe slowly and hold very still. Leica film cameras were made for low light. They’re pretty well-balanced so that you can hold them steady without a tripod. Because they’re rangefinders, they have no mirror—like an SLR does. With no mirror to “flip up” when you click the shutter, it was pretty easy to hold my Leica steady in low light. I usually used a 1/4 second exposure. Some pictures in the book are full one-second exposures. It wasn’t like I was drinking coffee at CBGBs, so my hands were pretty steady throughout the night. I couldn’t sit around and wait for digital sensors to be invented. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Did you ever worry about the effect all those darkroom chemicals could have on you?

GODLIS: No, never. That was a mark of your dedication to the darkroom. There’s a great photo of Walker Evans with his fingernails stained from developer. I always used my hands in the darkroom, but never got stained because I used these chemicals called SPRINT. You can still buy them. My darkroom teacher in Boston, Paul Krot, who taught at Rhode Island School of Design, started the company. He was kind of a mad genius who made environmentally friendly photo chemicals. It was the ’70s, you know. Kodak’s scientists couldn’t make improvements on their chemicals, because their marketing department didn’t want to print up new packaging. So their scientists would give Paul Krot their ideas, and he’d use them for SPRINT. He died a decade or so ago, but I still use SPRINT chemicals in his memory.

Kodak’s scientists couldn’t make improvements on their chemicals, because their marketing department didn’t want to print up new packaging.

What would you think of NYC if you arrived today, but were the same age you were when you first moved here in the early ‘70s?

GODLIS: I love NYC, so probably the same thing. It wasn’t like I thought when I got here that the city was in bad shape. I had been in Boston, and been robbed there three times—the last time at gunpoint. So I moved to NYC to be someplace safer. And I moved here to shoot street pictures. The worse the city looked, the better it was for my pictures.

New York City is still the best place to do street photography. Waves of people are always walking in your direction. Even if they are all looking down at their phones. Everyone’s got to walk on the street.

So the big difference today is the cost of living. I would have found out pretty quickly that I couldn’t find an apartment for $200. Where that would have led me, I don’t know. A better job probably. But I couldn’t have been luckier than to come when I did. I didn’t come to find punk, but it found me.

Who’s doing interesting street photography now?

GODLIS: Clay Benskin is probably the best around. Chris Stein has a new book out of his old street photography from the ’70s I’m looking forward to. Photography is full of great work, both in the past and the present.

Digital hasn’t killed anything. Just enhanced it.

Anything you miss about NYC of the ‘70s?

GODLIS: My telephone. The Saint Marks Cinema. My Dodge Dart. Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party. My phone machine. I have pictures of lots of the stuff I miss, so I can revisit things. People though, mostly people.

Anything you’re glad is gone?

GODLIS: Phonebooks.