On a cold winter’s night in the year 1919, a small council of unnamed US government officials sat down for a heavily-seasoned roasted duck dinner within the White House. In between unbearably slow sips of purified spring water and whole milk, an agreement was reached: the rest of the nation was far too in love with alcohol and everything was more-or-less going to hell because of it. Something had to be done.

After the final bite of delicious sliced duck had been taken, and subsequently thirty minutes allowed for #safe #digestion, our nation’s leaders reached a decision—one that would change the history of America as we know it. They decided to constitutionally ban alcohol nationwide, to make America sober (again). However, a rather obvious conflict existed—the citizens of our nation loved booze, and wished for it not to be taken away.

Police confiscating the goods. Photo: Wiki Archive

So on January 16, 1920, while the Prohibition’s ink was set to dry on some old, crinkly piece of papyrus that the government used to write all the important rules on, more entrepreneurial members on Long Island set their eyes on a new economic opportunity brought forth by the ban: the importation, transportation and distribution of a highly demanded product that now had virtually no established supply. Within roughly 24 hours of the dry edict, the underground economy for smuggling and running bottled alcohol was in full swing, and the East End—wonderfully equipped with harbors, bays and inlets—was on track to becoming the rum-running capital of America.

Under the blanket of night, boat-owning opportunists in Montauk made their way three miles offshore (later extended to 12 miles) to the international waterline—to what would soon become known as “Rum Row.” There, the rum-runners would rendezvous with multi-national bootleggers and attempt to bargain down captains offering rum, whiskey, and other well-traveled spirits in bulk, for sale and enjoyment back on the motherland.

The most well-known name on Rum Row in the Prohibition Era was said to be Captain Bill McCoy. Known for his undiluted Canadian whiskey and other authentic spirits, Bill McCoy became a reputable vendor in the rum-running operation—unlike other captains that watered down their goods for larger profit margins.

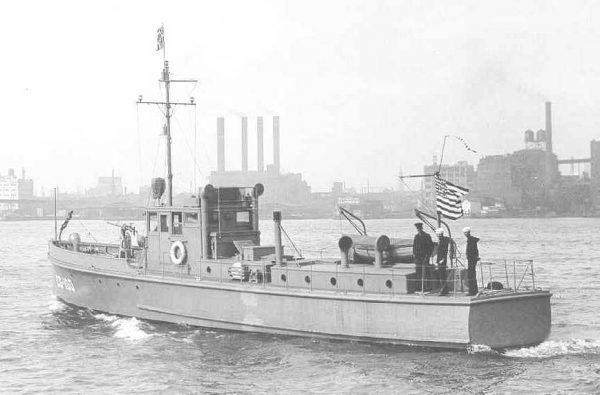

Coast Guard Patrol Boat. Photo: Wiki Archives

With newly purchased goods from legends like McCoy stored below deck, the rum-runners whipped back to the motherland—where illegal alcohol was stored in Montauk’s local marinas as well as other more than accommodating and well-patronized establishments, like the Island Club on Star Island. Whatever wasn’t drank by stash spot security, underage employees or the establishment’s loyal patrons, made its way to speakeasies up the island and toward the city.

The kicker is, while the black market that spawned from the Prohibition provided the East End, and its rum-runners, with a stream of both income and adult beverages for 13 years, it ultimately worsened nearly every one of our nation’s conditions that the government sought to improve with the act. Instead of reducing crime and corruption, it created a profitable market for already-established criminal organizations to expand into with ease. Instead of lowering the tax burden of prisons filled with drunks, it led to more raids and arrests than ever imagined. And instead of improving health and hygiene in America, it spawned speakeasies, weird code words, and an entire decade of tight-lipped drinking in dimly-lit attics and mold-infested basements.

For more oceanic tales from the East End, check out Sag Harbor’s Whaling Tales, and while you’re at it, discover five well-founded reasons to consider living on a sailboat.