When we talk about dream jobs, documenting the historic performances and the private lives of punk and rock and roll legends is probably near the top of the list for a lot of people.

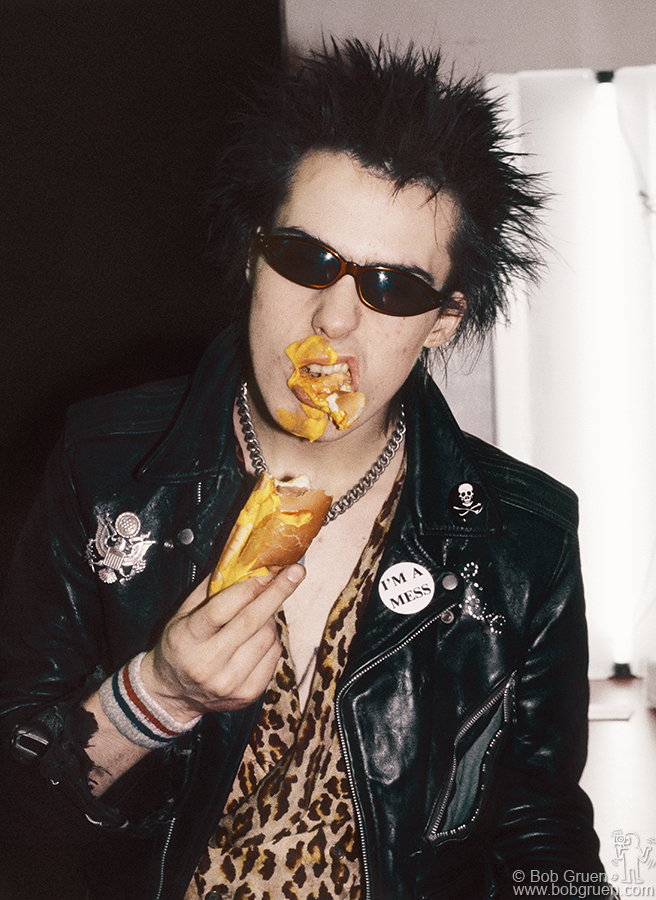

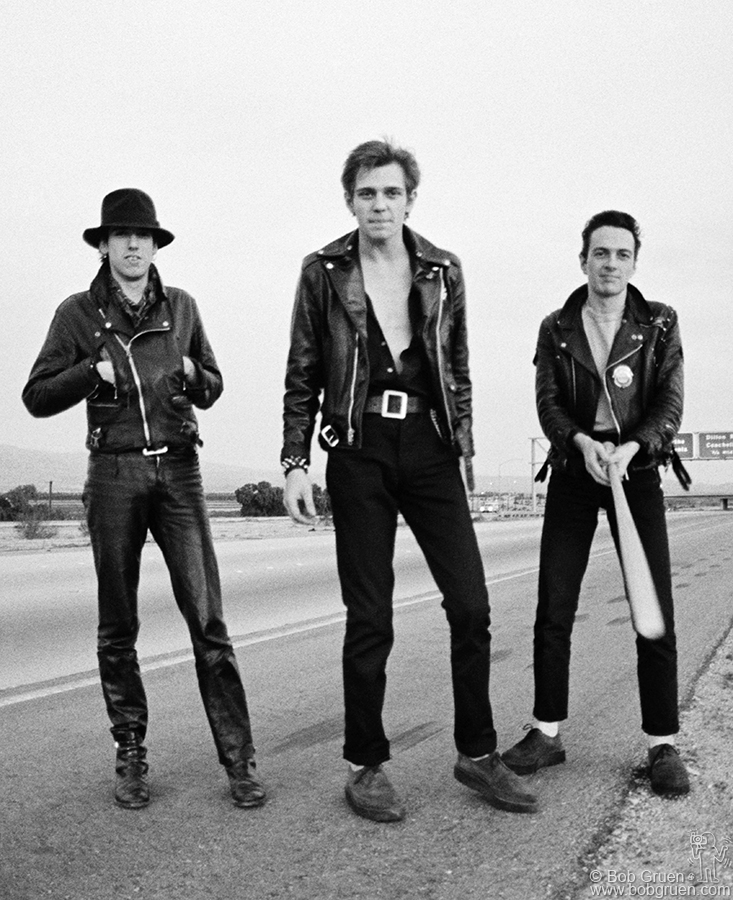

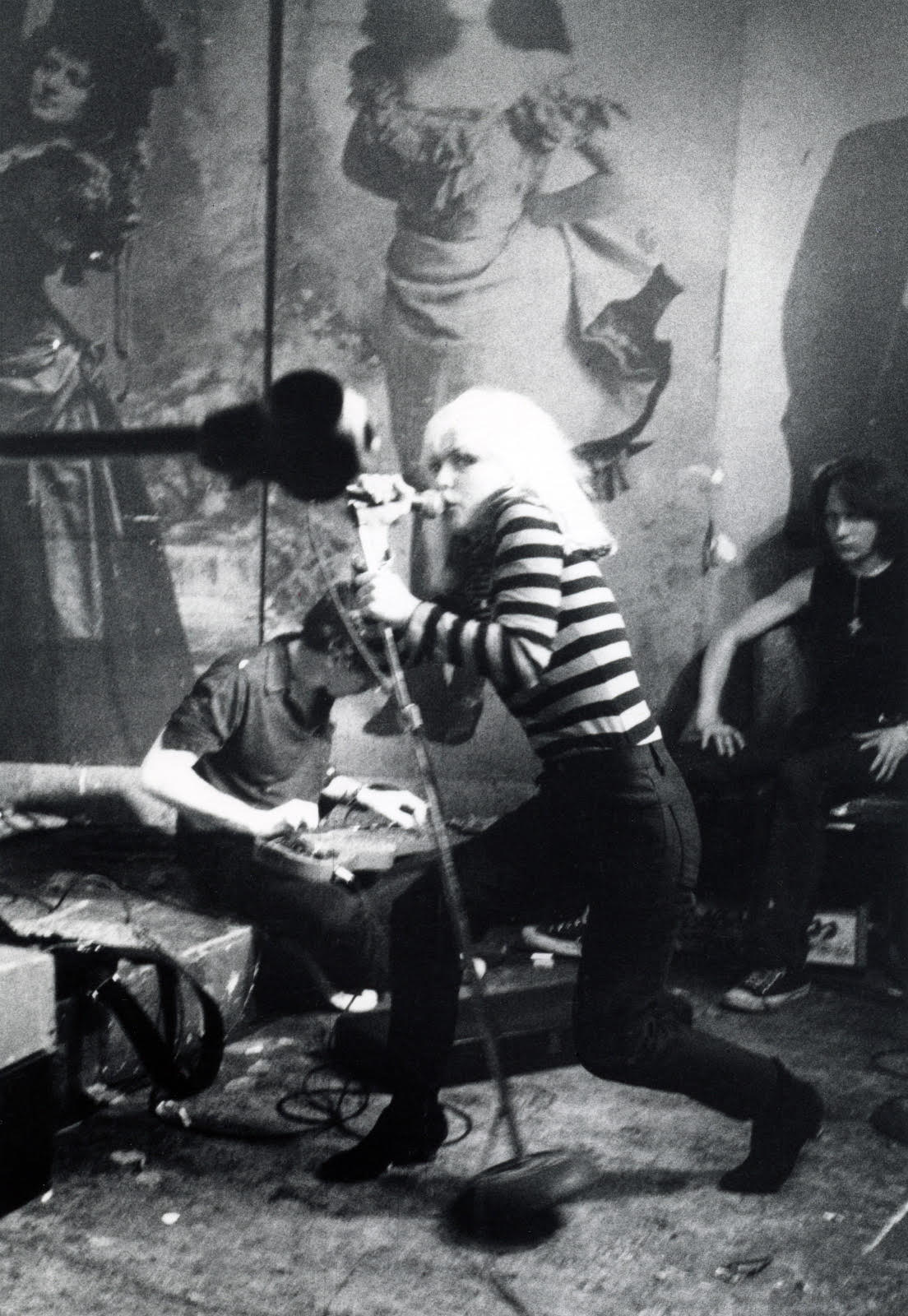

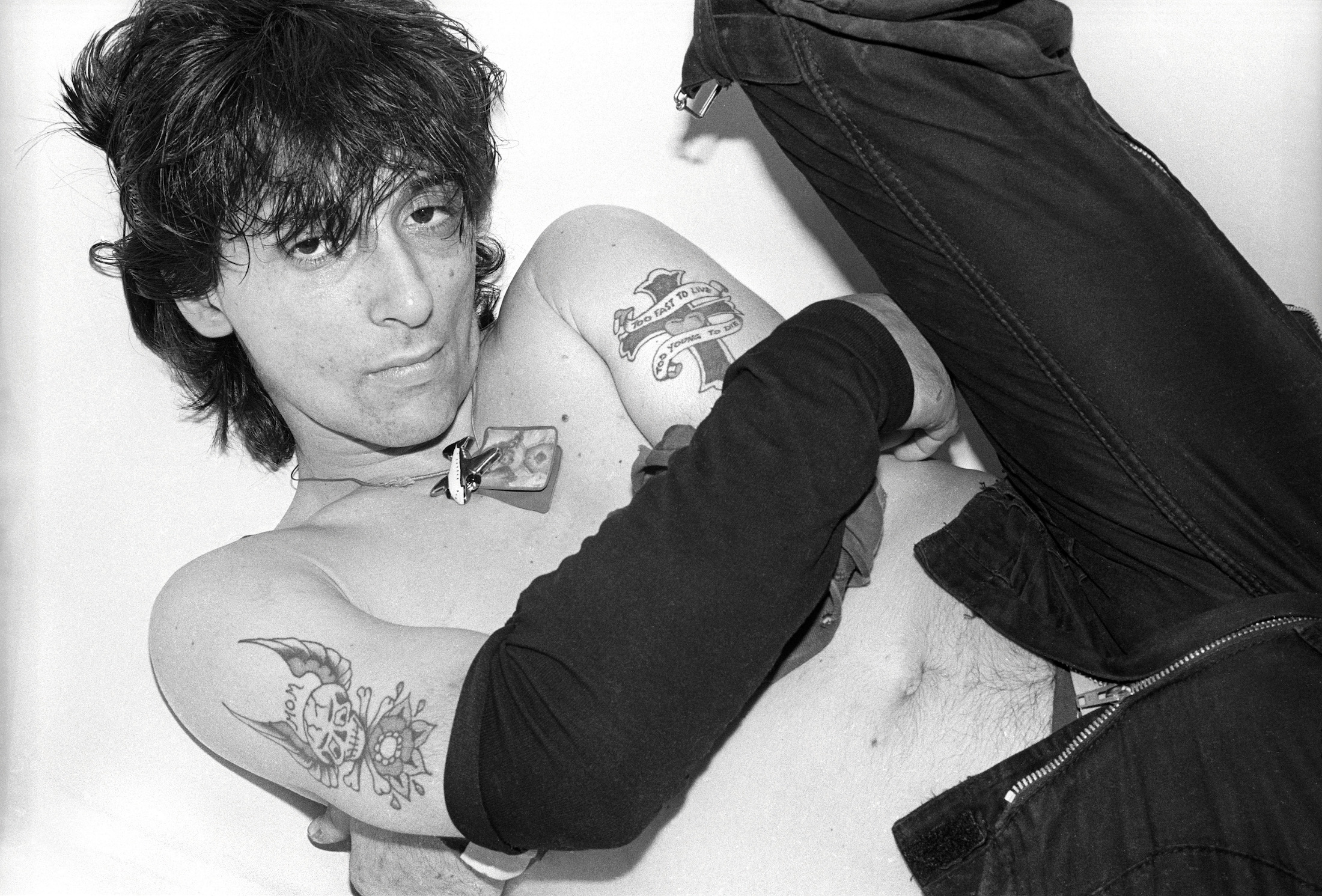

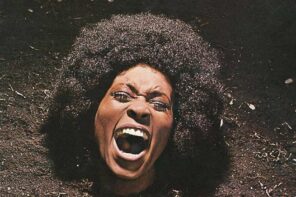

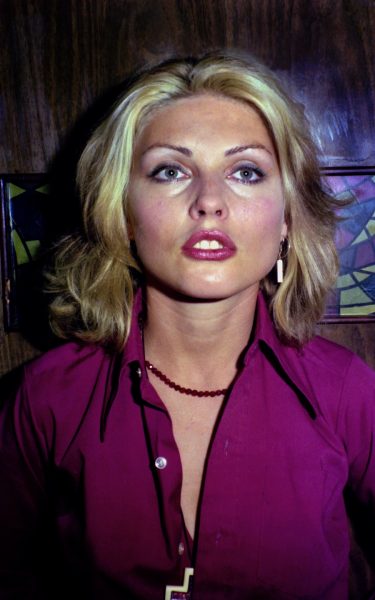

Last week the Museum of Arts and Design hosted Legends Behind the Lens, a punk rock photography panel discussion with New York’s most iconic punk rock photographers. Imagine the absolute pleasure of listening to the likes of Bob Gruen, David Godlis, Paul Zone and Marcia Resnick talking with Legs McNeil and sharing the stories behind their famous shots of musicians ranging from the likes of Patti Smith, Blondie, The Ramones, the Dead Boys and countless others. This discussion was nothing short of a fascinating reminiscence on Johnny Thunder’s love for posing, The Who’s performances on Central Park’s skating rink, Debbie Harry’s failure to take a bad photo and the wild nights at CBGBs.

Debbie Harry. Photo Paul Zone.

Post-panel, I had the incredible opportunity to interview a personal idol of mine, Bob Gruen. Gruen has photographed all your favorites across the rock and punk music scene, including The Rolling Stones, Bob Marley, Elton John, Queen, Bruce Springsteen, Iggy Pop and everyone in between. He’s published nine books, received numerous accolades, is an inductee in the Long Island Music Hall of Fame, has been featured in countless exhibits all over the world and was John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s personal photographer. While most four year olds are usually eating mud and picking their noses, Gruen was already learning how to develop photos from his mother. He acquired his first photo pass to the Newport Folk Festival in ’65 where the formerly-folkie Bob Dylan made his famous electric debut and was booed off the stage.

Gruen’s first major breakthrough came from the one and only Tina Turner, from there the rest was history, or so I hoped to find out. While I would have happily sat for hours listening to any story Bob would tell me about his life on the road with The Clash or photographing the early days of Led Zeppelin or being a friend of John and Yoko’s during their pivotal New York years, I am beyond grateful for the precious time I got. Aside from the sparkle that ignites in his eyes when he starts to tell a story, you would never just how accomplished this talented photographer is. Gruen’s modesty and humble disposition are as impossible to deny as his passion for music and the genuine relationships he’s formed with his subjects. I left the conversation invigorated by his career’s foundation of improvisation and hustle and his desire “to capture the feelings not just the facts.” So, thank you Bob Gruen for 22 minutes of inspiration and I too agree with you, rock and roll is freedom and the freedom to express your feelings…loudly.

The story of how photographing Dylan led to meeting Ike and Tina and that led to Elton John which led to John and Yoko, and that led to the Elephant’s Memory and they had the same manager as the New York Dolls which led to Aerosmith and then Malcolm McLaren and The Sex Pistols which led to The Clash, and so on…

McKenzie: So you mentioned that your mother introduced you to photography and I read that your first photo pass was at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, how did you get that photo pass?

Bob: A friend of my mom’s had a public relations company, mostly dealing with companies, but he was kind of a wise guy and he said I’ll write you a letter kid. He wrote a letter saying I was a photographer representing his company. So I got to Newport to the box office and they totally said get the hell outta here but I was determined and I wouldn’t take no for an answer. My mom always said that “no” is not necessarily the answer, but it could be the beginning of an interesting conversation. So I had an interesting conversation. And, after they realized I wouldn’t leave, they gave me a photo pass. I had my dad’s camera and film I had actually lifted from the backroom of a job. I had worked for a company that sold film and flash bulbs at the World’s Fair. They closed up because there wasn’t as much business as they thought, so when I left I took some film with me and that was all I had to photograph with. I wasn’t really working for anybody but it kind of started my career because I did get in the photo pit that weekend and I got pictures of the Weavers and Peter Paul and Mary and Tom Paxton, Phil Ochs and Muddy Waters and all those kind of people but it was the night that Bob Dylan came out and played in a band with an electric guitar, Muddy Waters used an electric guitar, but they didn’t make such an outrage about it, but when Dylan came out he was obviously playing not folk—it was more like rock and roll and a lot of people in the audience didn’t like that and a lot of people did. It wasn’t just booing, it was cheering and booing and fighting and yelling. I think that what it was, was that Bob Dylan was kind of announcing that rock and roll is the folk music of America and I think he was right about that, obviously.

It wasn’t just booing, it was cheering and booing and fighting and yelling.

But yeah that was my first taste of being in a photo pit and I liked it and I didn’t really pursue it because my idea in the ’60s was really not to work. I would get odd jobs to pay the rent… if we paid the rent, I mean, otherwise we get an apartment and you didn’t have to pay the rent for three months and it took that long to kick you out. When you’re 19, three months is a very long time so you can live there and have a good time and then get another job and get another apartment and keep going like that. So it wasn’t actually until 1969 when the band that I was living with, by that time they were called the Glitter House and they broke up and played one last gig and got discovered by Bob Crewe who is Rusev, The Four Seasons and one of the biggest producers in the world and he liked them and made a record for them. That record didn’t really go very far, but they introduced me to the record company and they hired me to take pictures for another group. I think the first one was Tommy James & The Shondells in a parking lot in Yonkers opening for Hubert Humphrey. I think that was ’68 actually. So then one thing lead to another and every time I went to a job, I would meet some more people and meet more people.

Then I met Ike and Tina Turner and they liked some pictures I did. That was another kind of accident. The first time I saw Tina we just went as people; I didn’t even have a camera. The second time a couple days later, they played in the nightclub so I could bring my camera at a nightclub. It was in a little bar on Queens Boulevard in the basement. I remember I was sitting on the floor taking pictures, but at the end of her act a strobe light flashed and she dances off and there’s a whole bunch of images flashing in front of you and I just opened the camera to a one second exposure to see what would happen. Three of the pictures are terrible and one of them is the best picture I ever took, because it really just captures the energy and excitement of Tina, like five images in one frame because Tina is way more than any one picture.

A couple days later we went to see them again and I brought the pictures with me with some of my friends and as we were walking out, one of my friends saw Ike Turner going from one dressing room to another and pushed me in front of Ike and said, “Show Ike the pictures.” And that changed my life because he liked the pictures. He took me into the dressing room to Tina and she liked the pictures. I started traveling with them and I met a guy through them, I met their publicist and he took me to a party and I met at another publicist and that guy talks a record company into hiring me to take pictures of this piano player coming from England for the first time in New York, turned out to be Elton John. He liked my pictures and he and I meet a few more times. So, it just kind of snowballed.

McKenzie: What was that moment like when you handed over those pictures to Tina Turner, I mean, you must have been like holy smokes?

Bob: Yes, I remember having trouble breathing. I couldn’t believe my life. You know, one minute I was a fan walking out to the parking lot with my friends and the next minute I was in the dressing room and Ike Turner was saying, “Tina look at these pictures.” And not only did she look at the five or six, cause I actually had a good night and I got five or six good pictures that night but I had two rolls of contact prints with me as well and I almost never show them but Tina started looking at the contact prints and she started liking all of them. I do remember that moment, being like, “Oh my gosh she’s liking all these pictures.” And very soon I connected with them and started travelling with them and it was a very natural situation.

I had the very first video camera that was commercially available. It was a half inch reel to reel, you had to thread the tape through the tape recorder and carry a 40-lb box. It was not like the color, stereo, high def in your phone that people have now. It was a big box that made black and white video of mono sound and didn’t really work in low light, but it was amazing because it worked at all and that you can go into a theater, tape a show and go into the dressing room or back to the hotel and show it back right away. No band ever saw themselves on stage unless you were on TV, even then it was usually live. You didn’t get to see a tape later; nobody had a tape machine at home. Unless you had enough money to make a movie and then develop it for a couple of weeks and hire a room to go watch them, nobody ever saw themselves. So the fact that I can bring this video tape and that I connected with Ike and Tina right at the beginning, Tina loved it that they could tape a show and then go back to the hotel and she could immediately go over it with Ike and they could point out ways to improve the act while it was so fresh in their minds. So my first album cover was with Tina Turner and it’s been snowballing ever since.

It’s just one thing after another.

McKenzie: In your career you must have a long highlight reel. What’s kind of on that reel for you?

Bob: It’s hard to pick a favorite. You know Tina Turner and that led to Elton John which led to John and Yoko, and that led to the Elephant’s Memory and they had the same manager as the New York Dolls which led me to Aerosmith and then when Malcolm [McLaren] showed up he was the only person I knew in England, so he introduced me to The Sex Pistols and then other people he introduced me to The Clash, Caroline Coon and Vivienne Westwood and they brought me to my first Clash show. So it’s just one thing after another. I’m hanging out with the Dolls and we used to go to CBs all the time. And then you get to know Patti Smith. The thing about CBGBs is it was a little bar full of all these people who had dropped out of everywhere else and we were all basically getting drunk and there were two sides to it, because on one hand—I’m listening to a friend of mine and he was saying artists came together to exchange ideas and improve and express themselves. And I said, they came for the miniskirts and to get drunk and get laid. And we were both right. Because it just happened to be a group of people that got together that really did influence each other and create amazing things. But yes, they were all trying to get laid and get drunk. I mean Legs [McNeil] talked about it, Legs was the drunkest! If you looked around the people at CBGBs you wouldn’t believe any of them could ever do anything and yet almost everybody did something or got to be something.

I just wanted to be comfortable someday and not worry about paying the rent.

McKenzie: And on the flip side of the highlight reel what’ve been the most challenging things you’ve faced as a rock and roll photographer?

Bob: Trying to pay the rent. Money. Money has always been stretched. It’s not a high-paying career. I don’t do the advertising jobs for $50,000. I do the publicity jobs for $50, $200. $500 is a lot, an album cover might pay $300. I mean money went a little further back then, back then $300 could actually pay the rent if you got a really good job, most jobs paid $75. But you know money, it was a big—it still is, I mean, fame doesn’t equal fortune. I don’t and never did make a lot of money, I just wanted to be comfortable someday and not worry about paying the rent. Some people would say access and things like that, but that’s always been a very spur-of-the-moment thing. People say how did you get a photo pass? It’s like, I don’t know maybe the publicist hired me to do it, maybe a magazine got me an assignment, maybe the drummer’s girlfriend wants to get pictures from me or maybe the manager heard about me, you know, maybe the promoter has some reason, I’ve gotten hired by the drum company because they want a picture of the drummer with the drums. Every day is different, there is no formula. But it’s always a hustle so you never have a steady job, you wake up every day unemployed. There’s a freedom of being free but that means unemployed.

McKenzie: Do you think your photography has evolved over the years?

Bob: Well I never really took much in the way of classes. I took one class one time because I thought I should know some facts. I took the class at Fashion Institute and actually when I met this professor to get in he said you can go right into the second-half advanced because you obviously have taken a lot pictures and I remember telling him well I never learned anything. I want to know the facts there might be things that I don’t know that amateurs know that I’m just doing something that you know, I want to find out. So I took two classes there.

In those days you didn’t even know if the exposure was right

But other than that, I’ve just learned as I go, and you do something, and it works out and so you try it again. My photography has always been very trial and error. I tell people that because you don’t know and in those days you didn’t even know if the exposure was right, you didn’t know until two days later. You’d get things developed and you’d know whether or not you got a picture. I remember a lot of time people saying “You get any good pictures tonight?” when I’m leaving the show, and I’d always say I hope so! Because you wouldn’t know until you develop it. Little things could be wrong, the setting could be wrong, too dark, too light, or someone just blinks at the wrong time. You know things like that. So it was so iffy. There’s a lot of worrying. So I tell people to take a lot of pictures. Because if you take a lot of pictures you are bound to get a couple of good ones and then if you only show the good ones people think you’re good.

McKenzie: So one common theme I think in punk and rock and roll specifically are these charismatic often fearless and free characters and personalities that are sometimes wild and unchained. What have you kind of learned spending lots of time with them? May not be just from a photography perspective.

Bob: Well I don’t know what you mean by them, I would call it us. I’ve had my wild moments too. Publicly I’m not one of them. I never really wanted to be the guy on stage in a sense of getting everybody’s attention. I sort of enjoy giving talks now at a more controlled level, but I’m not the guy who makes the whole stadium scream. But what have I learned from them? That everybody’s equal. That you know, there’s all kinds of people who are sensitive and express it in different ways. I know Steven Tyler and I know Suzanne Vega. They’re both super talented people with huge a following that inspire literally millions of people. They are quite different; they are very very different, so it would be hard to say what you learn from their personality in general, except that everybody is different, and everybody is human. A lot of people might have an ego and think they’re so special. I mean, it’s kind of silly sometimes watching somebody—they’re saying, ”I want the brown M&Ms and a certain brand of a kind of liquor” or whatever. Everybody is pretty equal actually.

What have I learned from them? That everybody’s equal.

McKenzie: Is there anything that has surprised you about your career? I mean, obviously I’m sure when you look back at yourself and that first photo pass at Newport, is there anything that has shocked you about the path of your career?

Bob: Oh sure I get shocked sometimes, I get shocked every other day! I turn around and go, “Oh my god look at that guy.” But I enjoy that. I mean it’s funny. You know, people get shocked in different ways. I’m not surprised with anything that anybody does. I’ve seen some of the most bizarre things happen. I saw my son born. That was shocking. You are in a room with two people and suddenly there’s three and he didn’t come in through the door and he’s as alive as we are. That was really weird. Hearing that John Lenon was dead was shocking. You know some of those things you never can get over. But it’s a way of saying it and a way of talking about it, Danny Fields is great about describing an evening and it just sounds like the most shocking events possible. I might have been at the same table and to me it’s just a normal bunch of nutty people. It’s all in how you describe it.

McKenzie: Did you ever get star struck or anything?

Bob: Not really. There were moments. I remember when I was first going to go and meet John and Yoko. Somebody asked me to come and take pictures for an interview and I got there and they said they just woke up and they didn’t want a photographer but don’t worry they’ll wake up and they’ll feel better and you can come up and take pictures and I’m like, “Yeah sure I’ll be in the bar. Let me know if it happens.” And then it happened. And he came and got me and I was walking down the hall and I remember that was really exciting. Meeting John and Yoko was more exciting. Some of the others were accidental or people who were talented, but they were John and Yoko. They were not just musicians but artists and artists in communication and media and affecting the whole world in a very very positive way. So at that point walking down the hall towards their room I was trembling. I remember that because I had to stop, literally stop and take a breath and I said, “Woah. I can’t shake, my camera will be shaking and it’s not gonna work, I’ll blow it!” The only thing I can do is just be me and try to do what it is I do and hope that they like it and if they don’t, then they don’t. But I don’t know them and they don’t know me and if I don’t know them I’ll still be me. So if they happen to like what I do then it will work out and that’s what happened. And they liked what I did but only because I took that moment to be me.

Some of the others were accidental or people who were talented, but they were John and Yoko.

McKenzie: In those moments did you know that you were documenting history not just taking pictures?

Bob: Well you don’t really know what history is going to be in the moment. I always knew that they were John and Yoko and they were special. In a sense of the whole world is watching. And at CBGBs to me it felt important, to me it felt like things, were you know—their music was getting better. I remember seeing bands having fun and then seeing them get really good at it.

There were a couple turning points. Talking Heads had this cyclical kind of sound that was very musical, that was complete and had a rolling in a sense. I don’t know how to describe it, their music. And one night I went like, “Wow, they’re really not just banging away on instruments like kids, they really have some sound here.” And one night when Blondie was playing and I think Robert Fripp was sitting in and I heard her sound and what they were doing, just feeling the audience reacting to I think “Heart of Gold” or something and realizing that’s something way bigger than this room. So in that sense there were moments when you would think it can’t be just here, it can’t be just us, other people are going to notice this. It’s too good. But not that it would end up in a Metropolitan Museum of Art kind of exhibit, no I didn’t expect that. When Vivienne put straps on pants, I thought that was the dumbest thing ever, who wants to tie their legs together? I saw a lady today in a very rich person’s brownstone and I thought do you really live here with your Ramones ripped knee jeans? That was not because they were rich and paying extra for pants that had been processed, it was because they couldn’t afford new ones. So it’s kind of funny to me to see jeans like that.

McKenzie: Tell me a story, a good story any story.

Bob: Oh God, out of the blue I don’t know, there’s so many. Well, I was staying up all night with Joe Strummer, the first time I talked to him. I met them at the Club Louise this place that Malcolm took me to and I saw their first show and I came back a year later and wanted to see them and the record company couldn’t really help me except tell me where they were. I went and things worked out and I got to see that show and afterwards connect with the manager and stay in the hotel and I was in bar drinking with them. I think it was the second or third night we were in some place on the coast of England that was far from anywhere and we were in this little old hotel and Joe Strummer and I stayed up all night playing the Bruce Springsteen song “Racing in The Street,” just that song over and over and we were talking until like dawn.

Around 6:30 in the morning he went to sleep, and I left and got my bags and went to the train station and got a one car little railroad train that took me to the next town that would have a four or five car commuter train to take me to Manchester. I remember getting into the train station and walking out and getting a cab that was going to take me to the airport. In those days you could go to the airport and if you had a ticket you could just get on any airline, they were the same price. So, I ended up on Indian airlines surrounded by people and everyone was eating curry and I just remember smelling curry all the way back to New York. And I get home and David Johansen calls me and says, “I’m playing tonight in New Jersey and this girl will take you there,” we’re in the Tomorrow club or something like that. I remember I didn’t even want to try, I was jet lagged and he said, “Don’t worry about it this girl will pick you up and take you there,” and she takes me there and we get to New Jersey and we’re looking around and we ended up in a parking lot asking for directions.

Now, the Bruce Springsteen song starts out in the 7/11 parking lot in New Jersey and I ended that night in the 7/11 parking lot in New Jersey and was thinking about poor Joe out there on the coast, damp and wet and there I was, he was just loving it. He had been dying to come over to America, they hadn’t come over yet.