A Journey into the Heart of Darkness

“Dad was never the same after Chiat\Day,” Lawrence Jr. told us. He steered a beaten and rusted Ford F250 pick-up truck along a ridge in New Mexico—somewhat precariously. The truck at one point had been a turquoise and white two-tone beauty but now showed more rust than paint. His words came carefully and slowly as he considered carefully what to divulge while we bounced along the pocked road (a word which is overly generous for that stretch of dirt, sand and rocks). The talk was in preparation for meeting his father, a furniture designer who is often credited in hushed tones around the Herman Miller Headquarters with having invented the office cubicle.

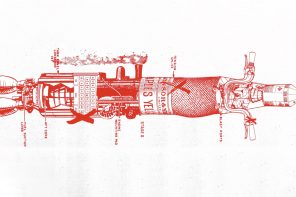

Officially, Robert Propst, who headed the research arm of Herman Miller and led the design of the “Action Office” system—what eventually became an erector-set-like furniture system that introduced cubicle culture to the world—is the “inventor” of the cubicle. Unofficially there’s a different story. Propst passed away in 2000, but lived long enough to see his team’s creation become a Dilbert punchline. Lawrence Jr.’s dad, who as a young designer under Propst conceived the Action Office II, the system that actually revolutionized the workplace after the more fanciful and individualistic Action I was rejected as extravagant by the sorts of corporate cogs who buy pencils and paperclips for offices, is very much alive, living in exile outside of Albuquerque. Some call him “the father of cubicle culture.”

Officially, Robert Propst, who headed the research arm of Herman Miller and led the design of the “Action Office” system—what eventually became an erector-set-like furniture system that introduced cubicle culture to the world—is the “inventor” of the cubicle. Unofficially there’s a different story. Propst passed away in 2000, but lived long enough to see his team’s creation become a Dilbert punchline. Lawrence Jr.’s dad, who as a young designer under Propst conceived the Action Office II, the system that actually revolutionized the workplace after the more fanciful and individualistic Action I was rejected as extravagant by the sorts of corporate cogs who buy pencils and paperclips for offices, is very much alive, living in exile outside of Albuquerque. Some call him “the father of cubicle culture.”

The invention had gone from something people fought for credit over to something they ran from blame for.

The slide of the utopian future the Action Office had promised into bleak territory was swift. By the late 1970s a combination of corporate tax incentives that made it appealing to replace furnishings often and the energy crisis, which introduced efficient but airtight buildings, made for a sickening situation. In some very literal as well as figurative senses. The evermore cheaply-made knockoff cubicles stuffed into increasingly close confines in stagnant, airless offices covered by overhead fluorescent lighting created a Reagan-era hellscape that saw a rash of workers coming down with bizarre chronic illnesses after inhaling the toxic pollutants off-gassing from the bargain-bin cubicles day after day.

Not all organizations are intelligent and progressive.

Probst himself came to regret what the Action Office had become. “Not all organizations are intelligent and progressive,” he said just a couple of years before his death. “Lots are run by crass people. They make little, bitty cubicles and stuff people in them. Barren, rathole places.”

By all accounts the backlash against the cubicle had taken a far more severe personal toll on Lawrence Jr’s father, the cubicle’s true inventor.

Down the River

It has taken us nearly a year to find him. All we knew going in was that he’d been a promising designer at Herman Miller who did much of the research, planning and drafting of the modular component office furniture system introduced to the world in 1968 by Herman Miller. The Herman Miller people had been no help to us in tracking him down, and indeed do not even acknowledge he worked on the program at all, referring us to their corporate website account of Robert Probst’s biography and a white paper when we ask about the invention of the cubicle. A series of tips from old associates and friends led us eventually to an ex-wife living in Manhattan Beach in Los Angeles and then to Lawrence Jr., which we might as well tell you right now is not his real name. Everyone we spoke to in connection in any way to the inventor of the cubicle insisted on anonymity for a number of reasons, including death threats.

“Death threats?” we asked the ex-wife when she mentioned this.

“Yes,” she said, taking a long drag on a 100-length cigarette and exhaling slowly out toward the beach, leaving traces of her orange-red lipstick on the white filter. From the second-floor balcony of her stuccoed condo you could see the waves rolling in. “Death threats,” she repeated, shaking her head of brassy blonde curls held in place with a large visor. We’d peg her for her late 60s, but the botox and other assumed assorted injections and hair dye made it difficult to tell.

Some magazine called my husband ‘The man who put the maze in the rat race,’ or some nonsense to that effect.

She lifted a finger from her cigarette, crooking a red nail at us and then recounted matter of factly, “We were living in the Valley. Our son was about 11, and there’d been an article in some magazine that called my husband ‘the man who put the maze in the rat race,’ or some nonsense to that effect. The angry phone calls started right after that. Sometimes the threats came in the mail, though, or in notes left on the front door. We moved soon after. First to Palm Springs then to San Bernardino. Once Bob died, my husband became the scapegoat for the whole damn thing. Then, that was it. We split up. He moved into a geodesic dome he designed and built himself in Wonder Valley, you know just outside Joshua Tree. Then he withdrew further and further until he ended up out where he is now. A truly godforsaken place.”

Never Get Out of the Fucking Boat

A few phone calls, a couple of drinks at Musso & Frank, a flight to Albuquerque International Sunport and a two-hour drive through what looks like a Wile E. Coyote cartoon later and there we were—heading deeper and deeper into the New Mexico desert in a Ford pickup with the sun beginning its slow sink.“Dad will tell you about Chiat,” Lawrence Jr. said. “I think he’s probably thought about it every day for the past 25 years.”

As what Lawrence Jr. called “the compound” came into view, the red and orange tint of the sunset gave its mismatched metal bones a warm glow. The assemblage of structures the inventor lived in was strikingly reminiscent of his great workplace innovation.

The stacks of worn shipping containers were set in ordered squares, two high and open to one side and surrounded by another row of containers at ground level, like a wall. It felt like a cubicle fortress. We parked near one opening and when we got out of the pickup we could smell burning wood immediately. We found him in the center of the courtyard, where he’d stoked a fire and suspended a heavy iron kettle over it from chains hanging from some handmade contraption that looked like it had been cobbled together from driftwood and a truck axl. “Mesquite,” he said by way of greeting, “Gathered from the desert.” Lawrence Jr. introduced us, then excused himself, disappearing into one of the containers, leaving us alone with his father. The overall impression he gave was slight and nebbish, moving in agitated motions and speaking with an air of forced calm, inhaling the mesquite scented air as if it charged him with serenity. He wore a tattered sweater vest and horn-rimmed glasses. If a movie were made of the inventor of the cubicle’s life story he’d be played by Alan Arkin. The conversation at first revolved around tea and things he’d collected from the surrounding desert (much of which was on display either piled in the courtyard or affixed to the sides of the containers).

“Would you like some pu’erh?” he asked. “It’s not to everyone’s liking. One of the only aged teas. Maybe the only one. I don’t know. It’s grown in China and then picked and dried and packed into bamboo. Then that’s all put in caves to age there. Like wine, you know? This is from the mid-’90s,” he said, scraping what looked like tar and tea leaves out of a stick of bamboo and into ceramic earthenware mugs without waiting for an answer. “It keeps well out here in the dry air. I’ve got loads of it buried over there,” he gestured toward a pile of rocks and doll heads and maybe parts of an airplane fuselage in the corner of the courtyard.

For all of the mess, there was order. The entire collection felt like a work in progress, with half-built contraptions resting here and there and the systems that were in place clearly assembled from spare parts.

Charlie Don’t Surf

We’d been advised to ease into things gently but were told he was eager to talk, and indeed, it didn’t take much to get him started. We mentioned the drive out being bumpy as we sipped our tea. “See that truck you came in on,” he asked? “It was built around the same time as the first Actions. Know why it’s still running? It’s still running because it’s built of components and when something wears out, you replace it. Nothing is made that way anymore. But that’s what we tried to do with the first Actions. It didn’t work. They were nice pieces of furniture. Beautiful. Beautiful. In fact, I’ll tell you a story:

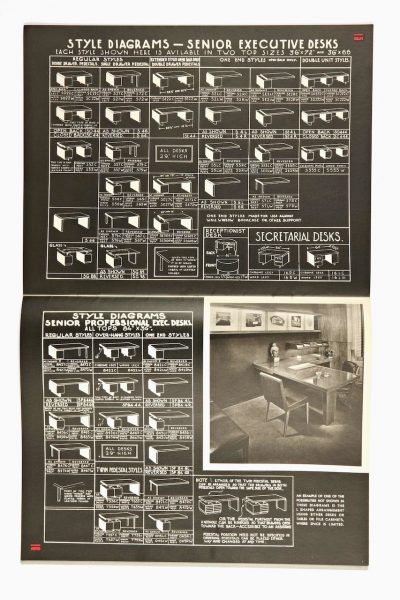

“We spent three years on just the desk for the Action Office, working with George Nelson’s people and our research team. The thing was gorgeous. The design flawless, with freestanding shelves and storage. Throw in the drafting tables and the perches and the cabinets and such and you could design private offices in open areas. That was the idea. We even had a standing desk. In 1965 we designed that. Way ahead of our time. All really well-made, with wood and vinyl and plastic parts throughout—all of it on aluminum bases. I’m sure some of it is still around. The type of stuff the collectors buy now. But here’s what happened. Are you listening? Here’s what happened. It wasn’t that nobody liked it. They loved it.

“At $400 or $500 for a desk, the executives balked. Too much money. And the stuff was too nice for the typing pool. But they bought it. They bought it OK. For themselves. They put the desks and the components in their homes. The first Action Office ended up in more living rooms than offices in 1965.

“So Bob, that’s Probst, right? He comes to me and he says we’ve got to go back to the drawing board and make this thing affordable so people will actually use it. Don’t make it so nice. Right? That’s where the acoustic mini-walls—they were supposed to be at various heights which would have preserved some feeling of openness but still helped with sound dampening—and that more box-like structure came in.”

“When you say box-like, do you mean like a cube?” we asked.

He scowled for a moment. “Yeah, like a cube. But here’s the important part. We weren’t trying to put people in boxes. Or cubes, or whatever. We wanted to set them free.

“Before our designs you either had a private office or you didn’t. And if you didn’t you were crammed into rows upon rows of desks in a big open room. We could have kept designing desks for those spaces but this was something else entirely. We wanted to liberate the common office worker from the tyranny of the open office. The vision was egalitarian.”

It’s still running because it’s built of components and when something wears out, you replace it. Nothing is made that way anymore.

He jumped up and said, “Do you know who Frederick Winslow Taylor was?” Our blank stares sent him running to one of the containers and when he slid the door open we saw books lining its walls. “He was one of the first ‘efficiency men.’ Taylorists were inspired by Henry Ford and the assembly line. Big fans of the open office plan,” he shouted from the container. “In 1917 one of his disciples W. H. Leffingwell wrote a theory of ‘Scientific Office Management.’” He rummaged through the container and came sprinting toward us, opened a dusty blue cloth-bound book near the fire and began reading out the full title: “‘A Report On The Results Of Applications Of The Taylor System Of Scientific Management To Offices, Supplemented With A Discussion Of How To Obtain The Most Important Of These Results.’ These guys saw human beings as nothing but a bunch of data. They’d make perfect fitness app developers.”

He stabbed his fingers at the pages of the book open before him, “In here, Leffingwell counts the steps it takes an employee to get to the water fountain. Put the water cooler in a bad place and it could lead to unnecessary miles being walked by the average worker—which, multiplied by many workers over 52 weeks, might mean tens of thousands of miles of wasted steps. And all that wasted time they could be working for the company. So the Taylor System offices consisted of close rows of desks packed into a large open space, perfectly arranged to facilitate the flow of bodies through space, with concern given only to the bottom line but not to how the people using them felt.

“We designed the Action Offices, both I and II, to be dynamic personal spaces that didn’t isolate workers and still allowed for collaboration and socializing. Everyone would have his or her own space and yet a communal feel would be preserved.

“Before that, you had people working elbow-to-elbow in, what today, you might call a progressive ‘open-plan’ if it had some damn kombucha on tap. These boiler-room sweatshops full of workers typing away and making telephone calls and banging away on adding machines and filing and chattering and doing a million other things were flanked by the executive office suites—or in some cases you had cruelly sequestered mazes of rooms. In any case, every desk had an intercom box on it and people communicated above the din through the crackle of those tiny, tiny speakers in voices sizzling through static like robots on the fritz.

“Our ideas were the antidote to all that. A reaction to the open office’s noise and distraction and chaos and lack of privacy and dehumanization.

We wanted to liberate the common office worker from the tyranny of the open office.

“We saw what was happening. Where this was going. We wanted to re-humanize the workforce. The original vision wasn’t cookie cutter at all. Far from it. The Action I had workers’ individuality factored in. They could be built into a really wide range of shapes and configurations incorporating all sorts of different styles and functions. All these supposed capitalists though, the people who ran the companies and watched the bottom line, didn’t like that. After the Action I flopped, and Probst was crushed by this, by the way—the feedback was to take some of the customizability out. They didn’t want their workers getting too comfortable or expressing themselves. The fear was that they’d work less efficiently, so the second version took that into account, that the market would need a more affordable, standard solution. With the Action Office II we tried to preserve the spirit and the intent of the first version but make it something that would be adopted. And adopted it was. The thing became a huge success. Highlight of my career if we’re being honest. At first, at least.

“The thing took off. Other furniture makers started copying us and doing it more and more cheaply, so pretty quickly our vision became degraded. What had once been driven by ideals of personal space and expression became defined by conformity and clutter.”

The Horror

The sun had set and we were now in darkness except for the fire and the moon. He stood straight up in front of the flames, which crackled in punctuation of his words and illuminated half his face with an amber glow. He’d become worked up and was nearly yelling: “They corrupted my ideas,” he shouted into the night. “They turned it into a goddamn ant farm.”

He realized how his voice had raised and that he was standing, shouting into a void in the desert. Maybe he’d done this many times before, the only difference being that we were here to record it this time. He composed himself and sat back down on a stool. He leaned in close to us and said in a low voice, “Every age has its marvels.”

We all sat for a long moment, sipping 25-year-old tea, and then we pushed him to explain. “Every age has its marvels,” he repeated, though this time his voice dripped with sarcasm. “This one is no different, nor was ours, nor the one before that with Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax Company Building and its pillars. We created the marvel of our age, a reaction to what was there before us, and now the new marvel is the reaction to what we wrought.

“These ‘marvels’ are like people inventing the universe. It was there already, wasn’t it? What I mean is, you didn’t invent anything by going back to the way offices were in the 1930s and adding a foosball table and some bean bags. The reaction to a divided office plan was just going back to what we reacted to originally. Fuck Chiat\Day. Gaetano Pesce, do you hear me? They are coming for you. Fuck open offices. A reckoning is coming.”

We had to ask, “Who is Gaetano Pesce?” He sipped his tea for a moment and then continued, retreating back to the forced calm.

“Pesce ‘invented’ the open-office plan when Chiat\Day commissioned him to create a modern office space in 1994. Sure, it had the added wrinkle of the telecommuting angle, but everything that cocksucker did was a repudiation of what we had done. It failed at Chiat\Day, spectacularly so, but his rhetoric about re-inventing office space for the 21st Century consigned me to this place,” he looked around ruefully, and his voice cracked. He pulled his glasses off and stopped speaking, staring at us for a long moment. Then he said softly, “The tide is turning. Gaetano might have envisioned the open office as if it were a playroom for preschoolers, but he still brought back the bad old days of workers sitting elbow-to-elbow bombarded by distractions. People are feeling the tyranny of the open office plan once more.” He met our gaze. Tears and rage welled up in his eyes. “They are coming for you, Gaetano. You’ll be right here with me soon.”

Then he stood up, the flames rising behind him and, for reasons unknown, quoted the Bhagavad Gita: “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”