Whether it’s a fully costumed mariachi trio stepping onto the F train brightening commuters’ morning for a few minutes before they get off at Union Square or the band playing romantic harmonies tableside while you and your date crunch tortilla chips awkwardly until they move to the next booth, the tradition of the mariachi as rambling musician blowing into town on a tumbleweed and a tune has real roots.

Similar to the blues in the United States, mariachi is a folk bouillabaisse of cultural influences stirred with the spoon of iterate labor. In the late 1800s, regional styles developed from the ingredients of Spanish theatrical orchestras mixed in with Native styles and a dash of African seasoning. As with many Mexican traditions, the Spanish provided the base—a full orchestra ensemble of violins, harps and guitars.

Mariachi band has always gotten the people moving—this was dance music and a party soundtrack played at the end of long days of labor by the very guys who had worked in the fields in the hot sun all day. You’ll recognize zapateado, a particular dance to the swaying harmonies and driving rhythms, by the dancers driving their heels into the ground in time to the music. Then, of course, there is jarabe tapatio, or “hat dance,” which has become the national dance of Mexico. While later, the mariachi became the band you invited to play celebrations of special occasion—weddings, quinceaneras, inaugurations, taco truck ribbon cuttings—back in those days the mariachi band was the celebration. An escape from the struggles of the day and a chance and get lost in the driving music—dancing and stomping into the night.

Back in those days the mariachi band was the celebration.

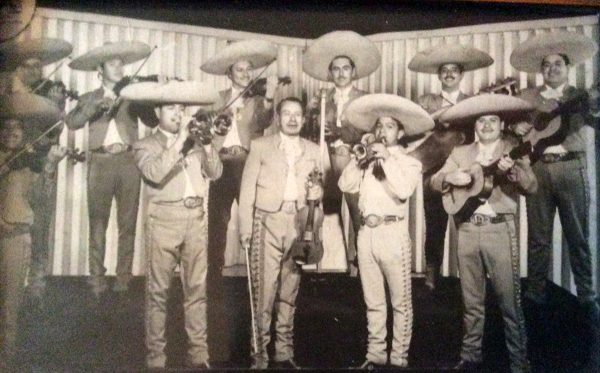

Mariachi Vargas, circa 1946. Back: Arturo Mendoza, Gonzalo Meza, Miguel Martínez, José Asunción Casillas, Roque Alcalá, Gaspar Vargas Front: Rubén Fuentes, Silvestre Vargas, José Contreras, Santiago Torres Colección de Miguel Martínez

As the mariachi wandered into the 1900s, a host of different guitars, including vihuelas and guitarrones, replaced the harps, likely because they traveled better and were more available. The Revolution brought upheaval to the haciendas the mariachi had traveled between working in the fields and many found themselves without their iterate labor wages. They still had their guitars though. And there we have the basis for the image of the dusty caballero, opening his guitar case, putting it out to collect a few pesos, and playing in the town square with his friends.

These musicians were much more than a precursor to touring musicians, swapping buses for burros, though. They brought with them, as they moved from town to town, epic tales of revolutionary heroes and scoundrels, and news from the war set to song. Wolf Blitzer with a guitar case and backup dancers.

Close your eyes for a moment. Picture a group of impressively mustachioed men—up to 20 strong—in broad hats and matching suits, strumming, singing, trilling and hooting. This now-classic conflagration didn’t take its first bow until the 1930s. Up until the mariachi bands were either near vagabonds or semi-professional regional groups, without much notoriety outside their area. Mariachi Vargas, founded in Jalisco by Gaspar Vargas in 1898 (and still playing to this day, with the reins handed down generation to generation) was nearly single-handedly responsible for that image you likely held in your head a moment ago. Up until the 1930s, the typical mariachi probably wore what was considered peasant clothing—loose white cotton pants and shirt and huaraches (a typical leather sandal). By contrast, Mariachi Vargas looked sharp. They donned traje de charro—a waist-length jacket and tight wool pants flared at the ankle to accommodate riding boots, all elaborately embroidered, a large bow tie, and, of course, the sombrero. But at this time something was still missing. A blare that you will immediately recognize as mariachi.By contrast, Mariachi Vargas looked sharp.

Cue the Trumpets

In the 1930s Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán moved from Jalisco to Mexico City and with it brought mariachi onto a bigger stage. Silvestre Vargas, Gaspar’s son, had taken over as the bandleader and he brought on Rubén Fuentes, the rare trained musician in the mariachi world at that time, as musical director. Mariachi entered the world of theaters and stage shows. And by the 1950s the horns now so associated with mariachi became a staple.

This could be the influence of jazz from the US and Cuban music, or, as one theory has it, a way to amplify the cacophonous joy of mariachi to be heard in film soundtracks.

Hollywood, or more accurately Mexico City’s studios, called and Mariachi Vargas picked up. The band became the face of mariachi to the world, appearing in more than 200 movies throughout the 1940s and ’50s, considered the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema.

This all cemented the classic image and sound we now immediately associate with mariachi and, to a great degree, dominated popular music style in Mexico after it exploded. Singers such as Pedro Infante, Lola Beltran, Jorge Negrete, Javier Solís and José Alfredo Jiménez (who is often hailed as the greatest actor of the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema) sang Rubén Fuentes’ Mariachi Vargas’s arrangements on radio, movies and television, bringing them far beyond Jalisco and Mexico City to the entire world.

The music permeated the identity of Mexico’s musical sound, look and style for decades, fracturing and morphing in pop music, even while the costume and sound of countless small groups across towns and cities in Mexico and the United States would be completely familiar to Silvestre Vargas and Rubén Fuentes to this day.

Juan Gabriel, in the 1980s, brought the tradition to Liberace-levels of excess. Mexico’s most prolific and best-selling singer and songwriter of all-time hit icon status in a career that began in the 1970s and spanned until his death in 2016. He was so beloved that Elvis-esque rumors regularly circulate that he is planning a comeback. Elvis’ Vegas jumpsuit, by the way, owed more than a few sequins to the mariachi. Viva Las Vegas, indeed.