A deep dive into what makes a great photograph according to legendary photographer and Whalebone Photo Contest judge Walter Iooss

Walter Iooss started shooting professionally at age 17 and went on to become one of the greatest sports photographers in the world, known for his images of Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant and Tiger Woods. We’re lucky to count him among the judging panel for the Whalebone Magazine Photo Issue Photography Contest for Photographers.

Walter was kind enough to share a bit of what he’s learned over a decades-long career in photography. He’s worked in so many conditions, shooting with almost nothing and improvising with table lamps to having nearly unlimited budgets. He says it all starts with three things: Light, Background, and Composition.

“That sounds easy but it’s not so easy to master,” Walter says. There’s also more to it. He shared some words of advice for photographers honing their craft from the wisdom of lessons learned along the way and memories behind some of the greatest sports photographs ever taken.

Photo Walter Iooss, The Catch, 1982

Walter Iooss shared with us on what to do when you have a once in a lifetime opportunity with the best athlete in the world, why a 50mm is the worst lens, how the subtle art of misdirection can lead to great photographs and The Decisive Moment.

How do you work with those three elements you mentioned, Light, Background and Composition?

Walter: I’m always concerned with the light and the background. I’m obsessed with backgrounds, because if you’re controlling the image and you’ve got a lousy background, you’ve got a lousy picture. You have to go to where you can get the picture you want with the background you want. I’ve always been drawn to that since I was I guess in my 20s. Someone once said I never met a wall I didn’t like because you always had a clean background.

Can you recall an instance where you had the light and the composition but not the background, and shifted things around?

Walter: One time, I was at a football game. There’s one background at the stadium that I liked. At the time I was using a 1,000-millimeter lens, back in the ’70s, and with a 1,000-millimeter lens your depth of field is about an inch so you know number one, you’re going to lose probably 80% of what you shoot because it’s going to be out of focus but if something happens in this one frame where I’m waiting for something to go past—this is in Los Angeles Coliseum where there was a staircase coming down and there were these colors and you sit there and at some point in the game something is going to happen in front of that. You gamble. It’s easy to take a good picture but you’re always looking for a great picture. If you’re a pro, you can take a good picture. That’s not that hard but I was always looking for something that was exceptional in baseball games, basketball, you’re always trying to find a look that makes it different.

So it takes a lot of patience first.

Walter: Then back in the ‘80s, at the Olympics in ’84, I’d find a spot, and other photographers started to know that where I was going would be the angle. I was with my assistant and I said, “Watch this.” Sometimes I would move to a spot that wasn’t a good spot to get them all over there and then I’d go back to the good spot. I’d actually do that to get the shot. A decoy.

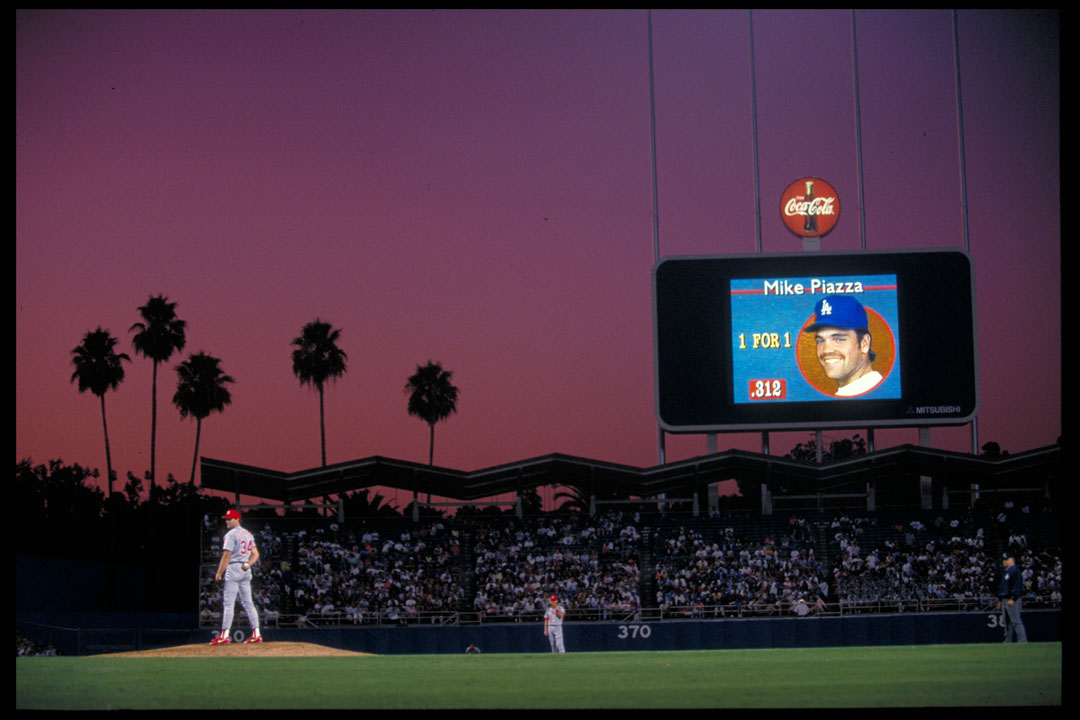

Sometimes it’s all the background. Photo Walter Iooss.

What elevates good photos to great photos?

Walter: Well, it depends how much concept is put into it sometimes. You can take a lucky picture. I don’t know if great pictures are lucky. There’s plenty out there that are right time, right place. None of us are shooting raising the flag at Iwo Jima. But so many of my pictures I try to make an image happen.

The surfing images I did in Kauai in 1976, I didn’t even know how to surf. I certainly, I mean I can swim, but I certainly couldn’t go in the water and shoot water pictures in Hawaii. I’d be dead. So with an unlimited budget from Sports Illustrated, six weeks on the North Shore, I had a helicopter and I had a pilot who was like my Fred Astaire if I were Ginger Rogers. We had both doors off and the swell would hit. And he sensed it, this guy Red Johnson. We’d go up and we’d hover above the lineup until someone was about to take off and drop down and drop in right in front of his face sometimes on the wave and ride down the face of the wave with him. It blew guys off the waves sometimes.

The pictures were unique. That’s where I had money behind me, but once again—an idea to take a picture that really wasn’t that high off the ground necessarily, in a chopper, you know. Of course, there were no air restrictions in Kauai you had to be 500 feet. Maybe my best angle was 15 feet above the water.

Photo Walter Iooss, Red Johnson piloting the chopper

Now maybe drones have really revolutionized that type of photography (and is a bit less risky for all involved). What do you think of them?

Walter: Are you kidding? They look pretty good. They get in positions I couldn’t get with the chopper. It’s a new invention and if you’re in the right spot once again or the right time with the right person—great things happen.

I had a pilot who was like my Fred Astaire if I were Ginger Rogers.

How else do you think equipment changes have advanced the art?

Walter: The whole aspect of photography’s changed so much because of the phone. I mean, I use the phone. I rarely carry a camera around. You always have a phone with you and so if something happens you can shoot. It’s sort of like the slightly wide-angle lens. It looks very nice but for my need because of my diaries or something, it works out. I think the variety of lenses is a big addition to making pictures too. The most boring lens in the world is the 50. One of the hardest lenses to use I think. It gets a little wide and you start to stretch out your reality and space but not everyone’s got the resources to buy the type of equipment. The equipment makes a difference if you know how to use it.

Photo Walter Iooss, Slam Dunk Contest, 1988

What’s something that somebody even shooting with a phone, one thing you think they could do to improve their photographs?

Walter: Good light. Look for the good light. Light always works. That’s why people like to shoot in morning or in the afternoon. The angle of the light, if you’re working in the studio, 90% of the time you’re working in the studio, you don’t have a light straight overhead. You want to bring an angle in so it looks good. Lighting’s essential—in all aspects.

Look for the good light. Light always works.

Photographers doing work in Africa where they have set up strobes and they do things, they’re making images. They’re thinking beyond just I’m going to shoot a line. They’re using their creative processes and the skills they have as a photographer to make something happen.

You have to make things happen as a photographer and a lot of times you can’t take no for an answer. I’ve been pushed out of a lot of situations, especially when I was young. I’ve been working since I was 17, I was just out of high school, as a professional and a lot of people resented me in the field back then. New York press, they treated me like I was vermin. Went to Boston—a kid from New York, New Jersey—I was a disgust to them. After a decade I guess you have to take your initiation fee and then they like you.

What’s something that you wish you had known when you were 17 and just starting out?

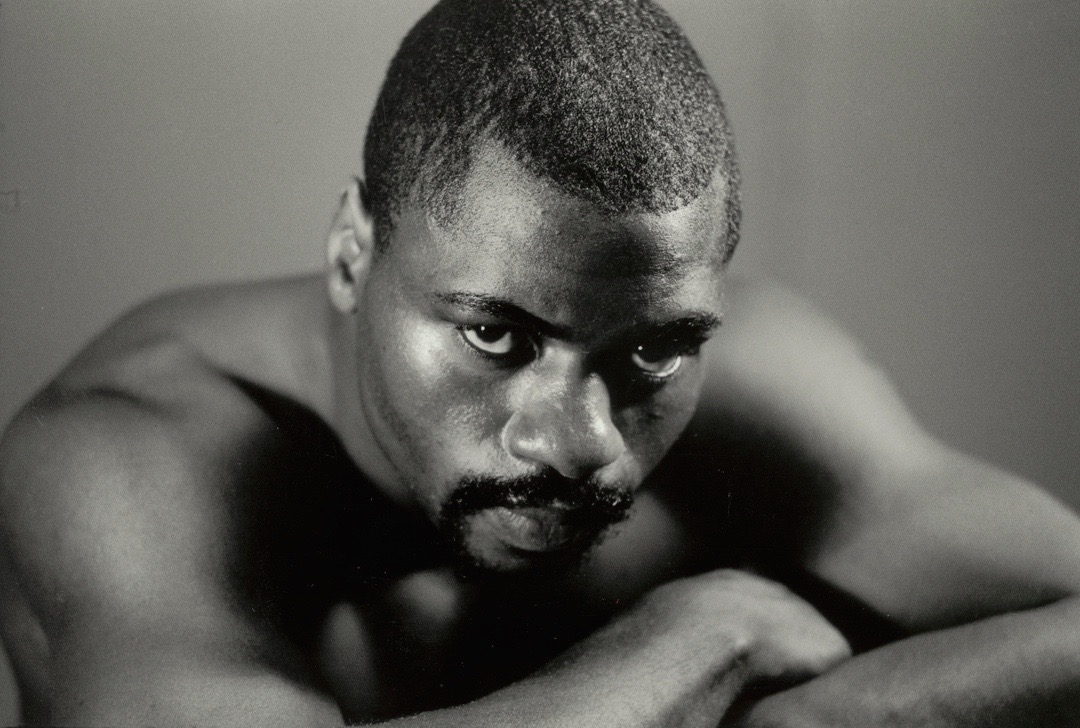

Walter: That’s a good question because photography’s an evolution. Certainly, I started off as an action photographer. That’s why they hired me. Sports Illustrated still needed some portraits but it wasn’t something I felt that natural at. I knew games, I knew athletes and I knew how they moved. That I already knew. I was obsessed with the way people moved their bodies, even when I was a kid watching on TV. I was very aware of what teams did on the field. The first good portrait I did—and this early, ’63—I went to this boxer’s house in Saddlebrook, New Jersey who became famous in the song called “Hurricane” by Bob Dylan. Reuben “Hurricane” Carter, his story is of being falsely convicted for murdering a guy in Patterson, New Jersey. I grew up in East Orange. East Orange and Patterson are two tough towns. They sent me to do a portrait and he’s sitting in his basement. I’m like, “What the hell am I going to do in here?” I have no lights.

There was an overhead bare bulb and I took two table lamps and I took the shades off them and put tables and lamps next to him and that’s my first good portrait.

Photo Walter Iooss, Reuben “Hurricane” Carter, 1963

Amazing. What led to that?

Walter: I don’t even know how I got there, but I did it. You start to get better but what happens is—I started to get tired or bored with action, so you start to look for different ways to see games. You’ve got to go and start looking at the field. Sometimes I turn my back on the game and look for everything that’s happening on the sidelines or in the benches or in the stands or against the walls and you start to branch out and then we went to what was called the action portrait where you would take a great athlete and I get him at 4:00 in the afternoon whether it was Jordan or Carl Lewis and I created basically a stage for these guys. Now I got the best athlete at my disposal for anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour in the best light and I’m his coach: “This is what we’re going to do. “

The most boring lens in the world is the 50. One of the hardest lenses to use I think.

At what point did you feel you’d found you own unique style as a photographer?

Walter: I’d say probably around 1980. Somewhere in there. In the ‘80s is when it all came to change. The Swimsuit Issue and had this big project for Fuji Films documenting US athletes training for the ’84 Olympic games, carte blanche. Do whatever you want. Money was no object. Once again, all the athletes at my disposal. I think that’s when it all started to change.

Walter Iooss shooting Luchadors in Mexico City with Whalebone Magazine. Video Robbie Burns.

Who are some other photographers whose work has particularly resonated with you?

Walter: Well, let’s go back to the most famous picture in history, Raising the Flag at Iwo Jima by Joe Rosenthal. More people have seen that picture. It was on a stamp. And one of the greatest photographs of all time—taken with a speed graphic 4×5 and one piece of sheet film.

Then all of Annie Leibovitz’s pictures.

James Nachtney. He does everything that’s horrible in the world and edge-to-edge—one of the greatest photographers—every millimeter in his frame is perfect. Edge to edge. That’s another thing that makes a great photographer. Using that frame and the frame is perfect. Certain photographers will never allow their work to be cropped. Nachtney’s one of them.

Mary Ellen Mark in the square format which I think is a very difficult format to work within with the Damm family living in a car. It was fantastic. Irving Penn, my lord. All the work he did in his studio, little studio. Another forgotten photographer is Pete Turner who revolutionized color photography.

Let’s not forget Peter Beard, because Peter Beard, obviously a great collagist, but he was a great photographer on top of it. You can collage all you want but if the main image was crap it wouldn’t look that good. All of those images that he would collage, many of them were beautiful images.

What are those qualities Peter’s images had that made them so special?

Walter: Because your eye went right to exactly what was happening. Either he took it wide and you see the expanse—because in a great photograph your eye doesn’t wander, it’s always driven to a point and then you can look out to the edge of what’s happening.

Look at Nachtney. We’re friends and we used to hang out. He’s a great Time photographer, always dapper. He’d be like in a war. His hair was always perfectly combed, shirt always pressed. “Jim, you’re in fucking Afghanistan. How do you look that way?” I said I was going to do a picture, I don’t know who I was shooting. I said, “Jim, I’m going to try to do one of your pictures today.” He cut off—it was a kid in a tank and the kid’s head was sticking out of the tank and one of the laws is never cut a person off at a joint. Not at his knees, not at his elbows—so he cropped the kid just below his nose, broke every rule of photography. Classic.

I said, “I’m going to try that picture. I’m going to try it with someone.” He says, “Keep trying,” and hung up the phone. You’re never going to do it, and he’s right.

Photo James Nachtwey, Grozny, Chechnya, 1996 (courtesy WILLAS Contemporary)

Any photos of your own that are, for whatever reason, personal favorites?

Walter: One of them was taken in Cuba in 1999 of kids playing stickball. And I love stickball. Stickball was my greatest passion as a child, and as a teenager, I had to work so I had to stop—it pissed me off in a way. When I was a kid I always remember a picture of a ballplayer, Willie Mays with the Giants. He used to play stickball in the Bronx in between the apartments. Before I was taking pictures, I was always interested in imagery. I wanted to take a picture, a perfect stickball picture. I went to Cuba to do children athletes. I’ve shot kids all over the world because if you don’t have a child’s heart or enthusiasm for sport I think you lose something. First, it’s when a pitch is delivered to you, nothing else in the world is happening. That millisecond when it’s delivered and you hit it, especially if you hit a homerun and drop the bat and you stand there, it’s like this is why sport is so great.

When a pitch is delivered to you, nothing else in the world is happening.

The last day of our second trip after three and a half weeks of Cuba we’re riding around in Little Havana and we see these kids playing. There’s this big fat kid up. The only overweight kid in Cuba. I took 20 pictures with a 50mm, a lens that’s the worst lens in the world, on some bad film I had—and you look at this picture and it’s perfect. There aren’t many perfect pictures. That’s one.

Michael Jordan’s Blue Dunk, because that’s a picture that was conceptually put together and utilizing a great athlete. I had this idea and then Sports Illustrated said all right we’re going to send you to Illinois to do Michael Jordan I said, “Here we go. Now I’ve got my vehicle.”

Photo Walter Iooss, Blue Dunk

So you had the image in mind before it was ever Michael Jordan?

Walter: Yes. Yeah, he didn’t know what the hell I’m going to do.

Two more: Then the ’88 slam dunk contest in Chicago which was another good one. Then I guess maybe the most famous or second famous of mine is what is called The Catch. Took place out in northern California. Dwight Clark’s catch: San Francisco-Dallas in 1982. With a 50 millimeter lens once again. Yeah. That’s like a moment in football history now, one of these things that stands out.

There are other better pictures along the way, but the kids in Cuba because my association and love children’s sport.

Photo Walter Iooss, Cuba, 1999

Maybe that’s not quantifiable but could you say what makes it perfect?

Walter: Yeah, because I don’t know how many pictures are perfect. The Blue Bunk is. I’ll give that 100%, too but in the Cuba photo nothing was placed. They’re completely different pictures. One is the right place, the right time after three and a half weeks.

I took 20 something frames. All the rest of them are horrible. I started out with a 4×5 and I was doing those Polaroids down there but it caused too much of a commotion once they see a Polaroid come out so we just went with the 50 which was the right lens.

Just the way all the kids are standing there. I didn’t arrange anyone. The girl with the dog and you see the ball coming in and every eye including the dog’s is on that taped up ball they created and there’s a kid with a yo-yo. You can see the yo-yo in the left side of the frame. That is what [Henri Cartier-]Bresson called “the decisive moment. “ You’re lucky to take one in your life.