Some have suggested that this project may not be for our time.

Joel Sartore and the Mission to Photograph Every Captive Species on Earth

“Can you hear me? I’m actually driving to a bat rehabber’s house right now. Found a big brown bat hanging from the wallpaper of my living room here in Lincoln. It’s cold here now in Nebraska, and when winter comes, we get the occasional small critter moving in to get warm if they can find a little opening. So I made a little house out of an empty cardboard box, put him in there, and am running him to a rehab center where he’ll live over winter. But enough about me. Let’s talk. This sounds fun.”

That was our initial introduction to Joel Sartore after we had a brief text exchange about being involved in this issue. If you’re not already familiar, Joel is doing much more than just helping one bat in Nebraska. Joel is the driving force and creator of the National Geographic Photo Ark project, a 25-year ongoing effort to document the approximately 12,000 species living in the world’s zoos, aquariums and wildlife sanctuaries.

“Where I get my energy from is the fact that for most of the animals I photograph, this is the only chance they’ll get to have their stories told to an international audience. For the rare ones, that means it’s the one and only time their voices will be heard before they go extinct. That’s a huge motivator for me, and a big honor. The world knows about tigers and chimpanzees and giraffes, but they don’t know about brown bats like the one I’m transporting this morning to safety. They don’t know about sparrows or toads, and they certainly don’t know much about snakes or minnows.

“At its most basic level, the Photo Ark is a visual record of what the Earth’s creatures look like. At current levels of consumption and habitat loss, we’re on track to lose half of all species by 2100. Not if I can help it.

For the rare ones, that means it’s the one and only time their voices will be heard before they go extinct.

“I believe deeply that people do care, and they want to help, but first they need to meet the animal. They won’t be moved to save anything if they don’t know it exists. They really have to fall in love with these creatures in order to be moved to save them.

“I’ve photographed 9,000 species now and growing. The goal is to get every captive species in the world. That’ll take another 15 years or so. By the way, we use black and white backgrounds to eliminate distractions and allow viewers to look each animal directly in the eye, to see that there’s great beauty and intelligence there. And on a clean background with no size comparisons, all animals are equal; a mouse is the same size as an elephant.

Look each animal directly in the eye, to see that there’s great beauty and intelligence there.

“But the cute animal portraits have a bigger mission; to teach the public that it’s critical to save vast tracks of intact rainforest, big sections of ocean that are not fished, coastlines that are lined with mangroves that nurture young fish. Without a healthy planet, it’s folly to think that humans will make it in the long run either.

“We ask that folks start simple though, by thinking of the things we all can do in our own backyards. Not putting chemicals over every inch of the land, from our lawns to our farm fields, would be a good place to start as this would reduce chemical pollution into our rivers and streams, the very water we drink. Plus we need pollinating insects to bring us fruits and vegetables. Eating less meat is another good thing because it takes so much fossil fuel and water to produce. Insulating your home saves carbon and actually makes you money each month. Energy efficient appliances do the same. It’s all these things that matter, including how we spend our money. There’s real power to save the Earth right in your purse or your wallet.”

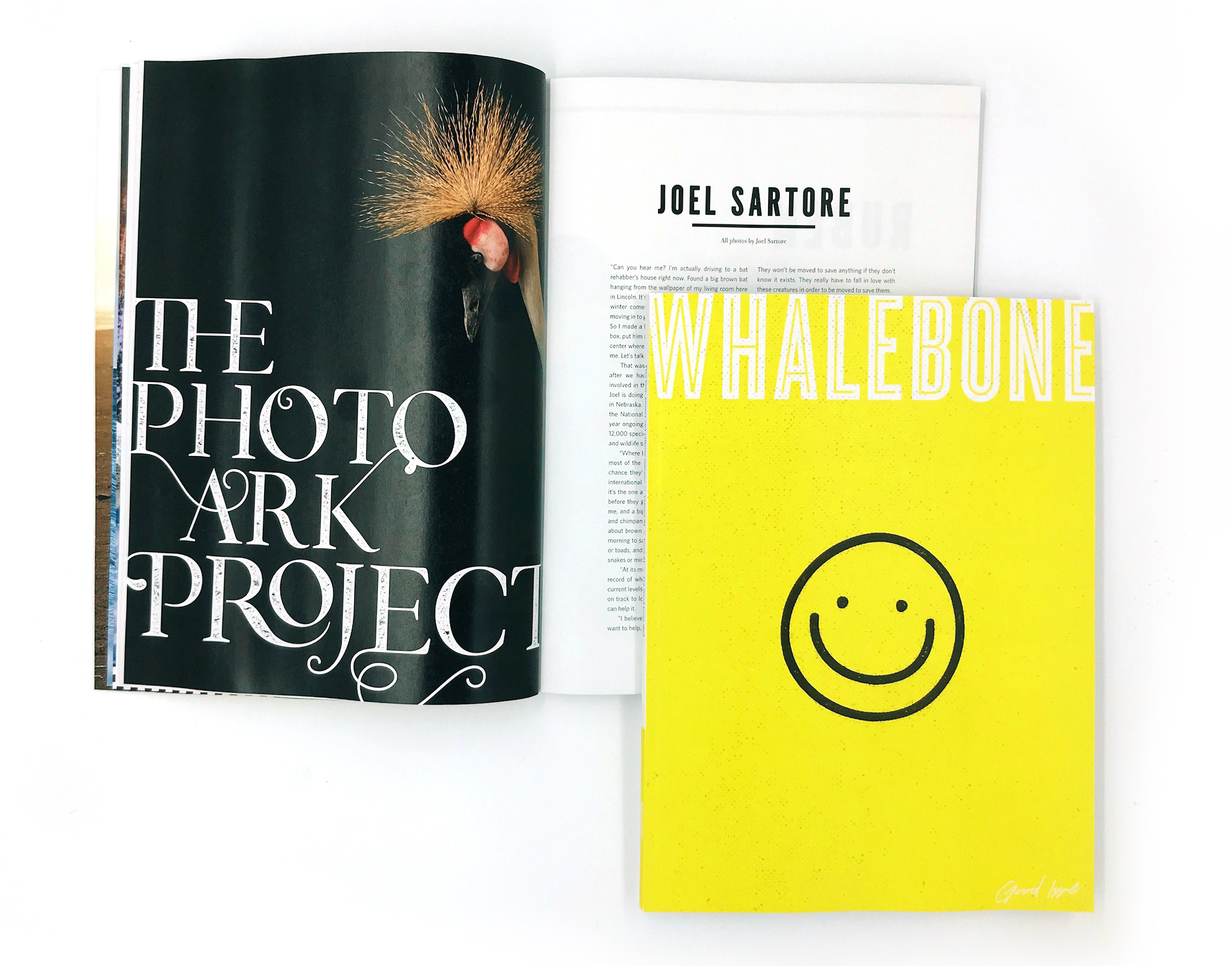

Whalebone Magazine is honored to share a little piece of Joel and his team’s work. He was kind enough to help out with a little behind the scenes from over the years.

A 3-month-old baby chimpanzee named Ruben at ZooTampa at Lowry Park. This little guy was being hand-raised because his mom didn’t want to take care of him. He was only comfortable if he was being held by his surrogate, human mom. So, they were holding onto him from the waist down, comforting him, then he got to showing off a little bit. Primates are so much like us, it’s remarkable. They play, they’re scared, they’re aggressive, they lie, they’re joyous. They like to laugh and then scream and get mad. Basically, they’re a lot like us.

Teiku is a 2-month old, federally endangered jaguar cub at the Parque Zoologico Nacional in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. My son actually got to bottle-feed that little guy.

That is a Brazilian porcupine at the Saint Louis Zoo. He looks like he’s shy, but he’s actually savoring some food they’d just given him, and hoping to get more. He’s an educational animal at the zoo, so he’s used to being fussed over.

An African elephant at the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo in Colorado Springs, Colorado. In exchange for some treats from her trainer, she was asked to open her mouth. At the moment the photo was taken, she quickly curled her trunk to get it up and out of the way, that’s why there’s some movement there.

This was the world’s very last Rabbs’ fringe-limbed tree frog. Nicknamed “Toughie” because he’d lived far longer than the normal lifespan of that species, he lived out his days at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens in Atlanta, Georgia. I photographed him several times over the years, and he was just an awesome animal. He seemed sweet in nature, and a time or two he hopped off the background and landed on my head or my camera, to get a better view I liked to think. He’s since passed away, and now there are no more. I show Toughie in every talk I give. I figure if I can get people to care about a brown frog the size of a baseball, I can get ’em to care about all the rest.

At the Pan American Conservation Association in Gamboa, Panama, a brown-throated sloth appears to grin at me. But sloths, like dolphins, look like they’re smiling all the time. I don’t know what he was thinking besides the fact that he wanted to climb up on me and have me hold him. This was at a rehab center for wounded and orphaned wildlife.

A Miller’s saki at the Cafam Zoo in Colombia. He looks very sad, doesn’t he? But actually he was just fine and he was eating treats. All that fur just makes him appear grouchy.

Photographed at the Budapest Zoo in Hungary, this Syrian brown bear was waiting to get pieces of fruit to be tossed to him. Eye contact is the critical component in these Photo Ark images.

That this cute, furry guy stood up and did this totally surprised me. This is a kinkajou at the New York State Zoo, and he’s just trying to look big and tough. Even though he’s sticking his tongue out, standing up is a defense mechanism—they want to show how big they are. But he’s actually not much larger than a toaster.

Joel Sartore as told to Whalebone Magazine

There are more humans alive than ever before, yet more of us know we can do many things to change the world for the better if only we try. But there’s no manual for it. The conservation heroes I’ve met each saw a need and tried to fill it, whether it’s saving rare primates in Vietnam or convincing restaurants to stop dispensing single-use plastics. Both are important.

Take Lynne, the lady who will care for the wayward bat that I’m bringing her today. She already has nearly two dozen other bats overwintering in an enclosure in her basement right now, along with several other small mammal species (rabbits and squirrels) that were too young or ill to be released once it got cold out. Her backyard is filled with wild birds that she’s nursed back to health. And she’s been doing this kind of work for more than 30 years. If anyone’s a wildlife hero, she is. In her kind and patient way, she’s saving the Earth, one species at a time.

I often wonder, what will it take to get us to turn away from the constant selfies and obsession with celebrity. Don’t folks know that we’ll soon be at a point where the planet’s climate will shift and life will become much harder, especially for humans? As these other species go away, so could we.

So I use the smiling animals, the cute babies, the fierce predators, and the colorful birds to try and lure the public into the tent of conservation and get them thinking. I hope to get people’s attention for a while, wading through all the electronic distractions long enough to share information about the ways we all can help—from recycling, to buying local produce to how we spend our money. Every time you break out your purse or your wallet, you’re voting. You’re saying to a retailer, “I approve of this product and I want you to do it again and again.” That’s even more powerful than the votes you cast at the ballot box, although that’s vitally important too.

I didn’t start out thinking I’d document everything in captivity around the world.

Look, I started the Photo Ark project to have something to shoot as my wife came out of chemo and radiation for breast cancer. I wanted to do something that would stick around longer than a monthly magazine story. And so this turned into something much bigger than I thought it would. I didn’t start out thinking I’d document everything in captivity around the world. But it is going to turn out to be the largest collection of studio portraits of biodiversity ever done. And just in time, I suppose.

I work in good zoos that provide abundant attention and care, but they can’t save everything. There are millions of species described so far, and zoos can only house, feed and breed a few thousand of them. And yet zoos are so vital. For the rarest species, many exist only in zoos at this point. They really are the keepers of the kingdom.

For the rarest species, many exist only in zoos at this point.

A lot of the animals that I photograph only exist in zoos now because their habitat has been destroyed. In places like the Lincoln Children’s Zoo and the Omaha Zoo here in Nebraska, some of the world’s rarest species are being captive bred to save them from extinction. Same for the Houston Zoo, the LA Zoo, the Phoenix Zoo, the Saint Louis Zoo, and so many more. Basically, all of these AZA-accredited zoos in the U.S. and others around the world have really high standards. And the educational outreach they provide year in, year out is admirable too. More than a hundred million people in this country go to a zoo every year in the States. For a lot of city dwellers, these are the last places they can go to actually see and smell and hear (and sometimes touch) a wild animal. That’s critically important in order to keep nature top of mind with people.

Most simply put, my job isn’t so different. My lot is to just do the job of introducing the world to all that’s at stake. And what high stakes they are indeed.

Some have suggested that this project may not be for our time. Perhaps the masses will pay attention, say, a hundred years from now. But I hope not. The goal really isn’t to create the world’s largest obituary. It is to change the trajectory of human behavior so that we save not only these species, but ourselves in the process.

See all the pretty pictures in print—the way God intended. Get The Good Issue.