Beyond the ‘No Entry’ sign everything happens in higher definition.

What started as anonymous teens scratching, marking and spray painting their names on walls to the millions of dollars that work by street artists can now fetch at galleries, the history of this brand of trespassing has always been, at its core, a declaration: “I was here. I exist.”

Off the Walls

A Brief History of Trespassing in the Greater Metropolitan Area

1968

Julio, a Puerto Rican teenager who lived at 204th street in Inwood, begins throwing up JULIO 204 all over the neighborhood. Others take notice, not sure at first what the letters mean, wondering if it’s a message that something is going to happen on February 4. Eventually, they discover it’s the work of one person, and the anonymous JULIO 204 becomes renowned in the neighborhood.

1971

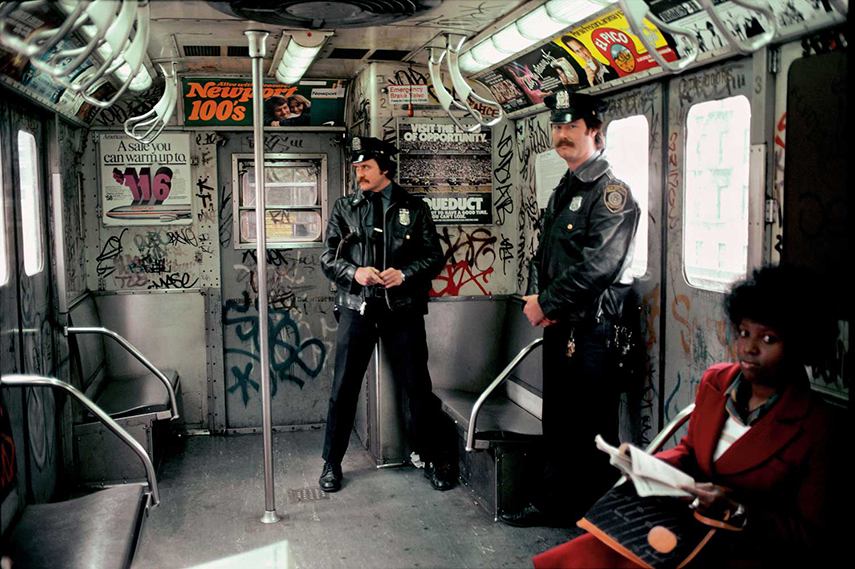

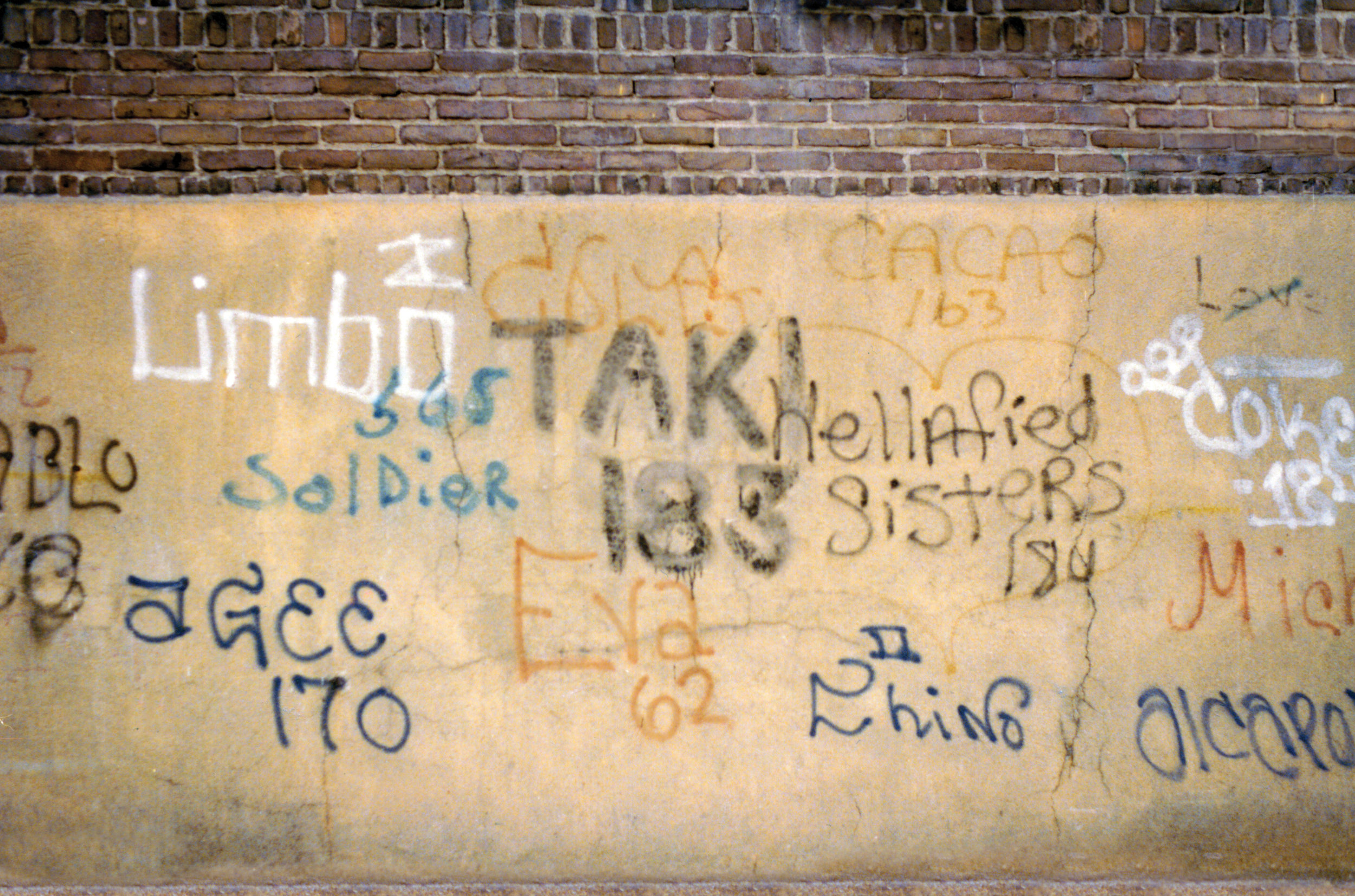

The likes of TAKI 183, CAY 161, JUNIOR 161, BARBARA 62, EEL 159, YANK 135 and scores of others follow JULIO 204’s lead and spray paint or marker their nicknames and street numbers mostly on walls, inside and out of subway cars and in tunnels, often scrawled in basic and hurried letters a few-inches-high and other times in more elaborate incarnations, declaring their existence to commuters passing by in letters six-feet tall and in technicolor.

Image courtesy TAKI 183

TAKI gets special notice, partly for being especially prolific, with his name appearing on subway cars all over the city, walls on Broadway, office building elevators, Kennedy International Airport and in New Jersey, Connecticut, and upstate New York. An article about him, a shy Greek teenager named Demetri (Taki is diminution of Demetri), in The New York Times in the Summer of 1971 led to him being crowned something of the father of modern graffiti.

1972

Almost overnight, the city had gone from very little graffiti to being covered in it.

Subway cars went all over the five boroughs, so the tags roamed the city, and as more and more people became inspired to make their own marks, graffiti spread with artists jockeying for notoriety. TAKI, years later, said part of “the great fun of it was to be a celebrity that nobody knows.”

TAKI, years later, said part of ‘the great fun of it was to be a celebrity that nobody knows.’

1973

The competition spurred creativity, and to gain notice among (and right on top of) the messy and oftentimes sloppy work of those who went before, scribbling their names on blank walls in small letters, the work became more and more stylized.

STAYHIGH 149 gets his name out all over the city and is one of the first to combine such ubiquity with style, incorporating fights of fancy into his lettering and dominating cars with eight-letter-long names emblazoned on them.

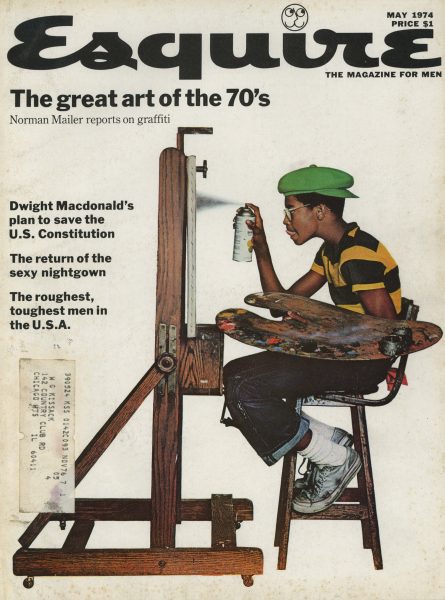

1974

Norman Mailer publishes an essay in Esquire magazine in which he wonders if graffiti is “the great art of the ’70s.” In it, he captures the creativity at play and the danger, writing, “There was real fear of being caught. Pain and humiliation were the implacable dues and not all graffiti artists showed equal grace under such pressure. Some wrote like cowards, timidly, furtively, jerkily. ‘Man, you got messed-up handwriting,’ was the condemnation of their peers.”

1975

Whole-car painting becomes a thing, where artists usually tag cars in big letters aiming for legibility, CLIFF 159 in 1975 begins a series where he surrounds his name with characters from the comics such as Dick Tracy and Beetle Bailey. BUTCH and CASE also make a name for themselves with their distinct style of elaborately bombing entire train cars in the Bronx.

Image courtesy Beside Colors

1977

BLADE’s overlapping 3D letters and geometric forms first appear on trains coming out of the Bronx in 1975 covering whole cars, playing with perspective and pushing creativity in the crews forward. He’s often credited with pioneering Blockbuster letters in 1977 with COMET. The large, square letters tilting back and forth maximize space, covering other’s work and enabling BLADE and COMET to paint whole cars quickly.

1978

On a handball court outside of Corlears Junior High School 56 on the Lower East Side, a colorful mural taking up an entire handball wall and depicting Howard the Duck shielding himself with a garbage can lid from the explosive block letters LEE is painted by Lee Quiñones. It’s the first of its kind and contains the message, “Graffiti is art and if art is a crime, please God, forgive me.”

Graffiti is art and if art is a crime, please God, forgive me.

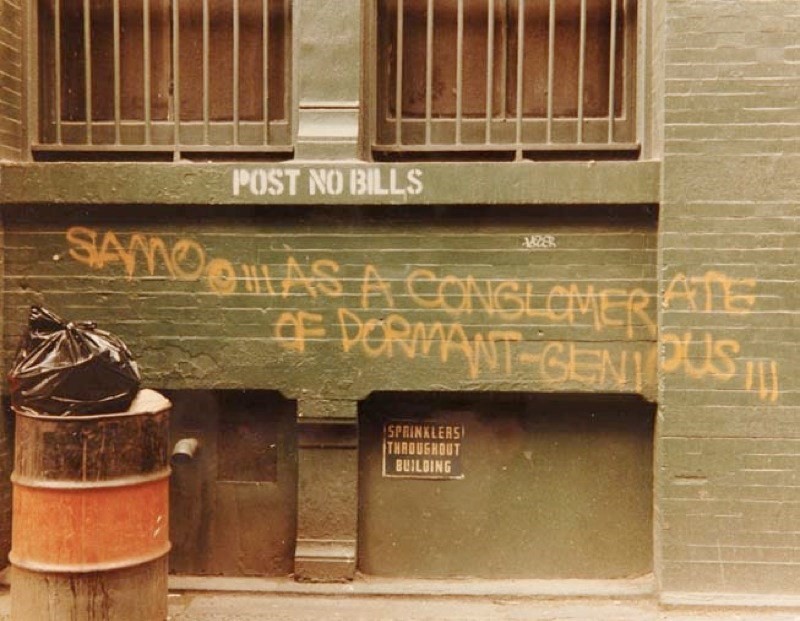

1980

SAMO IS DEAD—the three-word announcement heralding the end of SAMO, the collaboration between Jean-Michel Basquiat and his partner Al Diaz. Since 1977, cryptic and sometimes politically charged messages had been painted by Basquiat and Diaz all over the city, but especially downtown, inspired perhaps more by ancient Greco-Roman graffiti than subway writers. They signed the messages SAMO, which was short for “same old shit.” This was the end of that, but the beginning of Basquiat’s painting career.

Image courtesy SAMO© Archive

1981

The Mudd Club group exhibition “Beyond Words,” includes the work of graffiti writers like DAZE as well Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring.

1982

In his first major mural, Keith Haring paints the Bowery Wall at the corner of Houston and Bowery with his graffiti-inspired pop art. The wall has long been something of flash-point in creative battles over the years.

In something of a publicity stunt, Mayor Ed Koch brings members of the media to an isolated train yard to show them a newly cleaned subway car painted white and touted a new security system that would keep the train pristine. It was too delicious and obvious a canvas to resist though, and the clean, white look didn’t last long.

Graffiti pioneer Lady Pink is moved to paint a canvas, “The Death of Graffiti,” in which a naked woman is seen standing on a mountain of spray cans pointing to a passing subway line. Behind the lead car tagged by SEEN and PINK, is a white car.

Photograph by Martha Cooper/Steven Kasher Gallery

1983

Jenny Holzer, a Rhode Island School of Design graduate and gallery artist, begins her “Survival” series—placing stickers all over the City with phrases and slogans such as, “PUT FOOD OUT IN THE SAME PLACE EVERY DAY AND TALK TO THE PEOPLE WHO COME TO EAT AND ORGANIZE THEM.”

1984

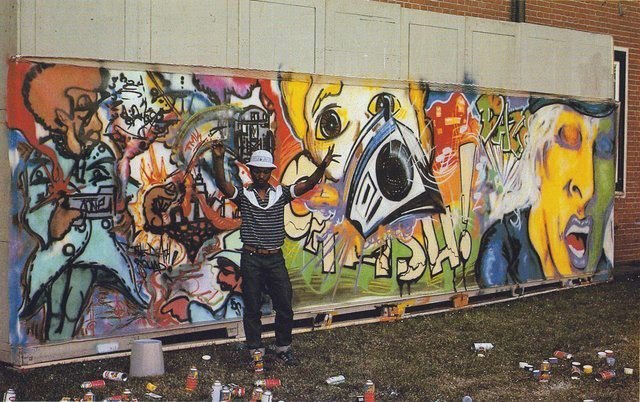

CRASH and DAZE are among the first graffiti writers to make money selling canvases and move from subway cars to canvases and galleries with a show at the Sidney Janis Gallery. Many subway graffiti artists follow suit.

Image courtesy Speerstra

1989

In May 1989, the MTA and the city celebrated a graffiti-free subway system. Just a few years before, in 1984, the MTA estimated 80 percent of cars in the line were tagged.

1994

Dan Witz puts up his Hoody Project, consisting of 75 separate ghostly hoodies wheat-pasted on boarded-up windows on the LES. “It was a complicated piece strategically, involving military precision, midnight missions, and the generous help of many friends,” Witz said.

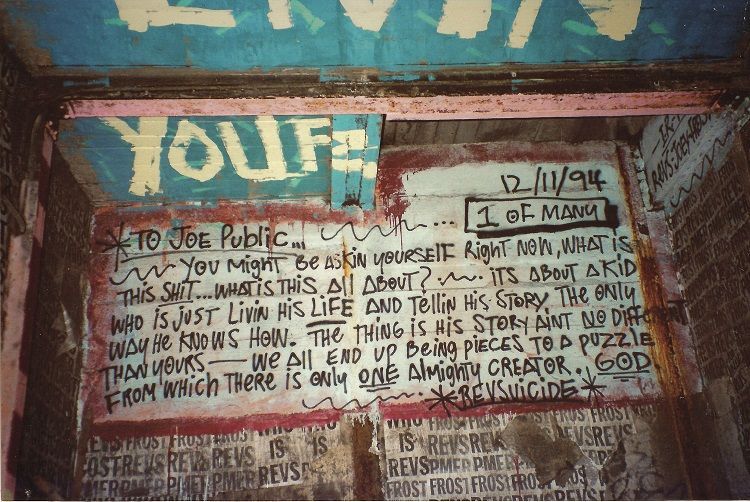

Graffiti legend REVS begins writing his sprawling subterranean 235 “page” autobiography painting a seeming stream-of-conscious scribbled text of his life’s story on walls through the deepest reaches of subway tunnels. The NYPD read the pages, working to pull details enough to biographical details of the elusive artist’s life to catch up with him to no avail.

Above-ground REVS remains as visible as ever, rolling massive letters in seemingly inaccessible places that would require ladders and harnesses to paint.

Image courtesy Public Delivery

1996

KAWS moves from large-scale letter bombing, mostly around to his home in New Jersey, to ad disruptions throughout New York, with his day-glow characters with Xs for eyes creepily inserted in bus shelter and subway ads.

Image courtesy TimeHD

2008

The long deteriorating Bowery Wall (Haring’s original mural had been tagged countless times and painted over) becomes a curated space for international artists with a program launched by Tony Goldman (whose Goldman properties owns the building) and gallerist Jeffrey Deitch, kicked off with a recreation of Haring’s original.

Lazarides, the London gallery that represents Banksy, mounts a massive group installation show in an empty building on Houston and Bowery including Faile, Paul Insect, JR, Antony Micallef, Jonathan Yeo, Miranda Donovan, Invader, David Choe, Mark Jenkins, Todd James, Vhils, Polly Morgan, Mode 2, BAST, Conor Harrington and Zevs, who paints the Channel logo in black paint on a nude model sitting on a cube live on the opening night.

2009

New Yorkers ask “what or who is BNE?” after postcard-sized white stickers with BNE in black letters quickly become a part of the fabric of the streetscape, appearing on mailboxes, phone booths, signs, walls, parking meters, streetlights and just about anywhere else they seem to turn. They sort of get their answer when the graffiti artist has a gallery show later that year.

Dick Chicken also bursts onto the scene with the tag DICKCHICKEN going up around Brooklyn and Manhattan on walls and objects in spray paint and evolving into many forms on stickers and stencil. Often it’s a simple stencil of a chicken with a dick for a head, but also includes all manner of dick-related poultry ranging from a Keith Haring-inspired figure on all fours with a chicken with a dick for a head as its head to a Tweety Bird character with a dick coming out of its head to a Sriracha logo with a dick for a head. You get the idea.

Image courtesy NEWYORKSHITTY

2010

Shepard Fairey’s piece at the Bowery Wall (done on plywood over the wall) is regularly defaced after it goes up, until a hole is torn in the plywood, exposing the actual wall beneath. Street art is still a battleground.

Mr. Brainwash, the moniker of Frenchman Thierry Guetta who was supposedly obsessively making a documentary about street artists that he never finished, which Banksy himself completed and released as the Academy Award-winning documentary “Exit Through the Gift Shop” has a large-scale solo show of his own work in an abandoned warehouse in the Meat Packing District. If it all sounds apocryphal, that’s because it probably is.

2013

Before it was an Instagram text style, Barbara Kruger’s Futura Bold white lettering on a red background gave voice to her often activist inclinations in everything from stickerings around the city to gallery shows. In 2013, Supreme, which had basically ripped off Kruger’s style for its logo sued Supreme Bitch, a woman-run parody for its appropriation of Supreme’s appropriation, which Kruger seemed to have tolerated up to that point. When asked for her response to the lawsuit, Kruger sent a Microsoft Word doc with the filename fools.doc that contained this text: “What a ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers.”

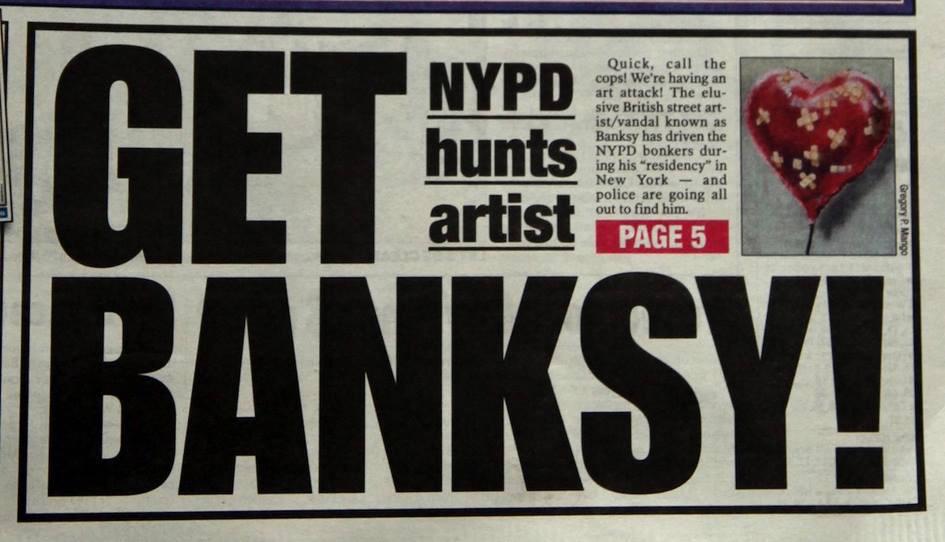

2014

Banksy uses the entire city of New York (and its inhabitants and their reactions to the work) as his canvas in a month-long residency.