A Costa Rican bean makes its way to the big apple

Written by Emily Bloch

By the time a latte finds its way to you, it has already been handed off by dozens of people. Indeed, the coffee served by Daughter—a community space, coffee shop, and wine bar in Brooklyn—takes quite a journey before it is transformed into a single-origin iced coffee or a mocha with house-made chocolate sauce. In the spring, the coffee drinks at Daughter tend to feature bold, sweet beans grown in Costa Rican cities and territories, like Miramar and Chayote, and the Brooklyn roastery SEY. “A lot of Costa Rican coffees use the honey process, which is letting the pulp from the coffee sit on the seed,” says Daughter co-founder Adam Keita. “A lot of those sugars sink into the drink, giving more fruit notes.”That makes them perfect for a caffeine buzz on a spring morning. But first, those brave li’l beans? They travel… “The process usually goes from farm to processing mill,” Keita explained. “The green buyer would [go to Costa Rica], sample a rough version of what the coffee would taste like, and then decide what comes to the states. Next, it’s cargo out to Jersey, and then finally to the roaster and then to us. The process is usually a few months.” Here’s a breakdown.

History

Coffee plants play a substantial role in Costa Rican history. In the early 1800s, the newly established government gave coffee farmers land to help ramp up economically. Coffee’s presence in Costa Rica helped the new country grow and develop quickly. By the 1830s, coffee export revenue outperformed the country’s sugar, tobacco, and cacao export rates. Today, coffee remains one of the country’s most important cash crops.

Growing

Coffee plants, which look like bushes and don’t have to be replanted every year, are grown across different regions in Costa Rica, each known for different flavor profiles and traits. Costa Rica lends itself well to coffee plants because of its volcanic soil, warm climate, high altitudes, and humidity. New crops begin each May with the first rains of the year. The plant sprouts white flowers. From there, the coffee cherries appear, and the fruit ripens until harvest season, in the fall. According to Keita at Daughter, while some coffee roasters offer Costa Rican beans year-round, special industry coffee roasters will sell beans from different regions based on the season.

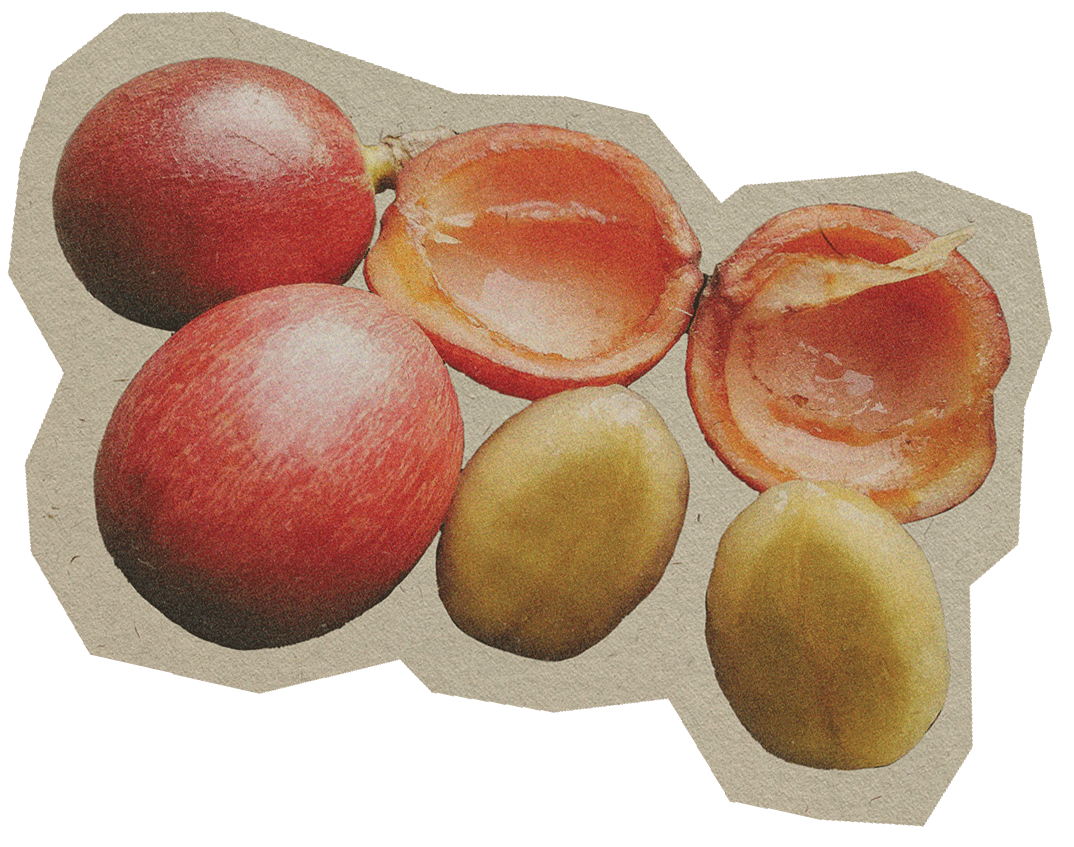

Harvesting

Once the coffee cherry is ripe enough, it’s time to be harvested. The cherry will be milled and separated, removing the fruit and outer layers covering the seeds which will eventually roast into the familiar beans we know and love. From there, the seeds will ferment and dry out. Once ready, it will be sorted and graded for quality. Then, the green coffee seeds are sent out to get roasted.

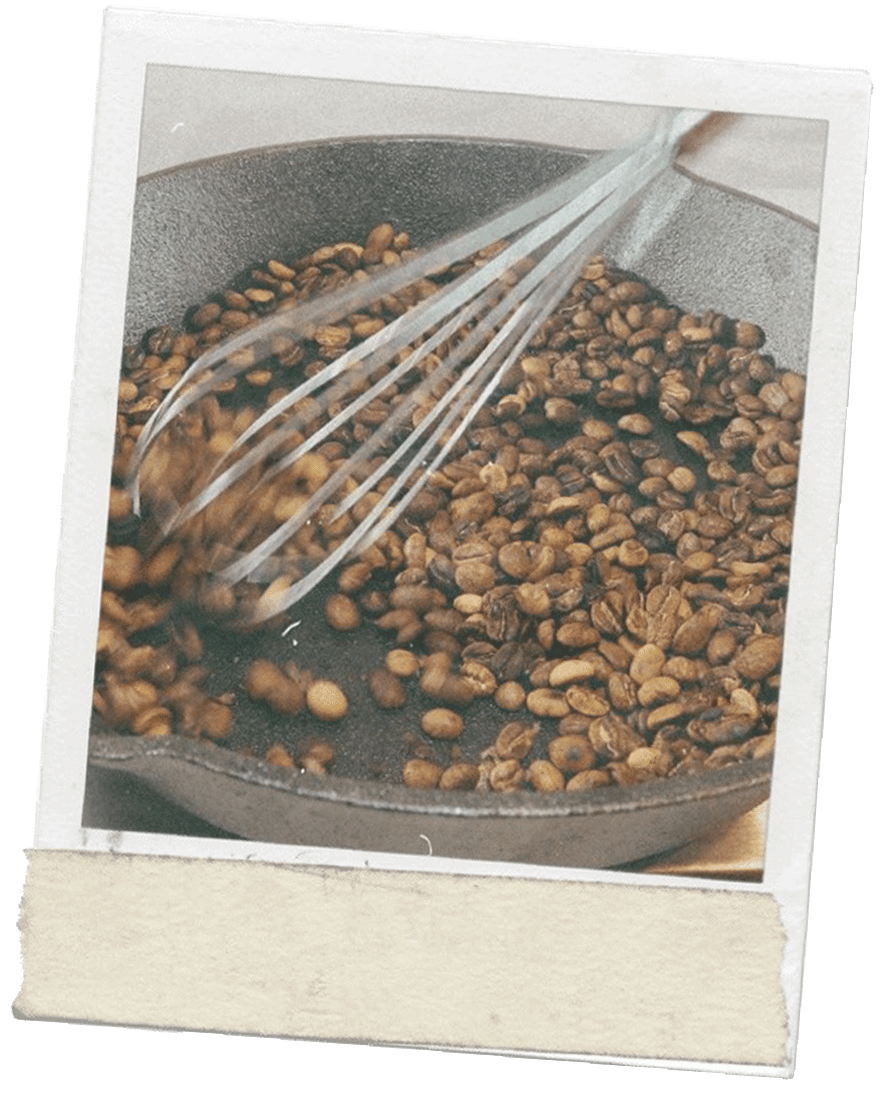

Roasting

Roasting is the process that transforms coffee beans from green to their signature brown hue. The lightness or darkness of a roast depends on the time and temperature beans are roasted. Costa Rican blends usually skew toward light to medium to accentuate their bright flavor profile, but factors can vary. Before they’re roasted, coffee beans don’t look like the coffee you’re used to buying from a grocery store or seeing in a local shop. They smell grassy. Roasting is what releases the aroma and profile you know and love.

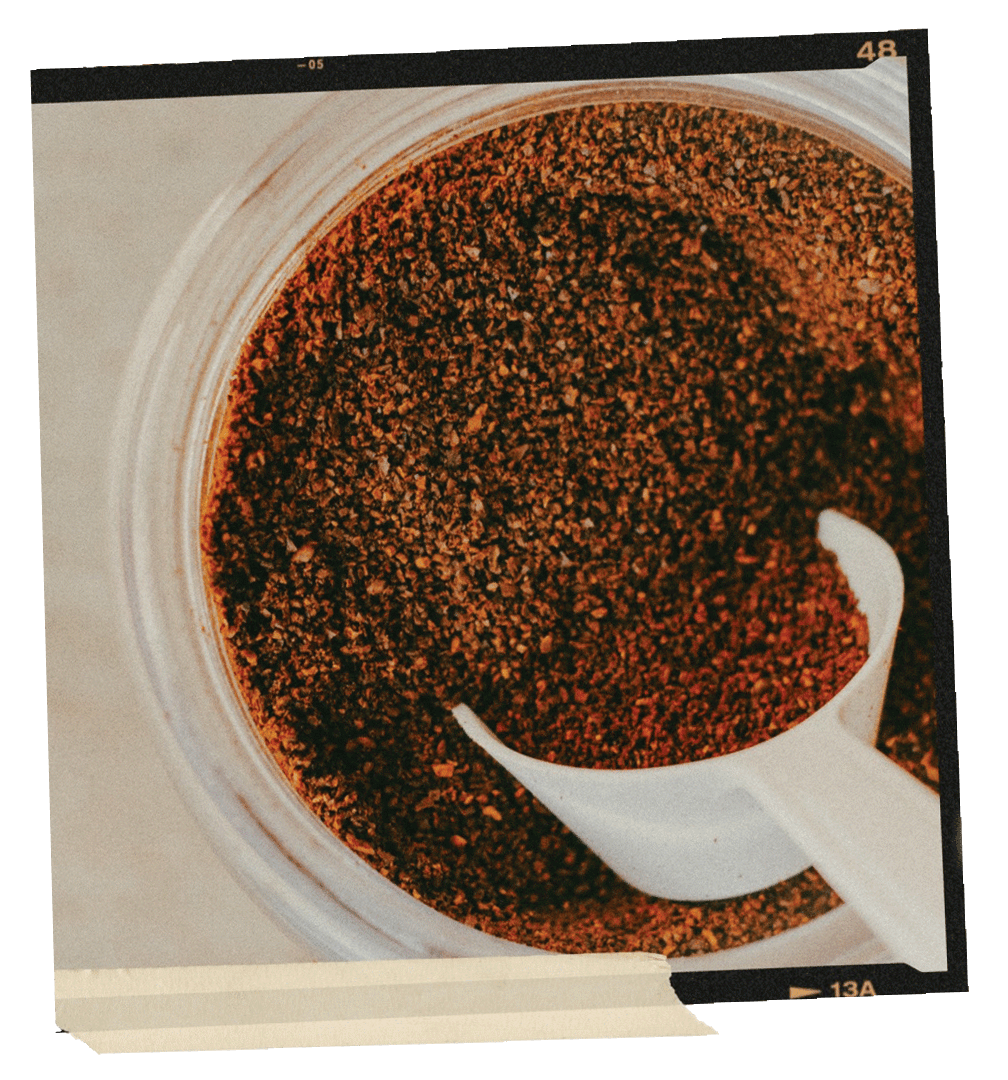

Grinding

Coffee grinding breaks down the beans into smaller particles so the flavor and oils can be extracted. The way the beans are ground can drastically change how coffee is prepared and served. Coarse grinds need more time in the water, while finer grinds need only quick exposure. A French press or pour-over calls for a coarser grind, while an espresso needs a finer grind. Even at home, it’s ideal to wait to grind your beans until the last possible moment. That’s because ground coffee beans deteriorate more quickly than whole roasted beans since more of their surface area is exposed to oxygen.

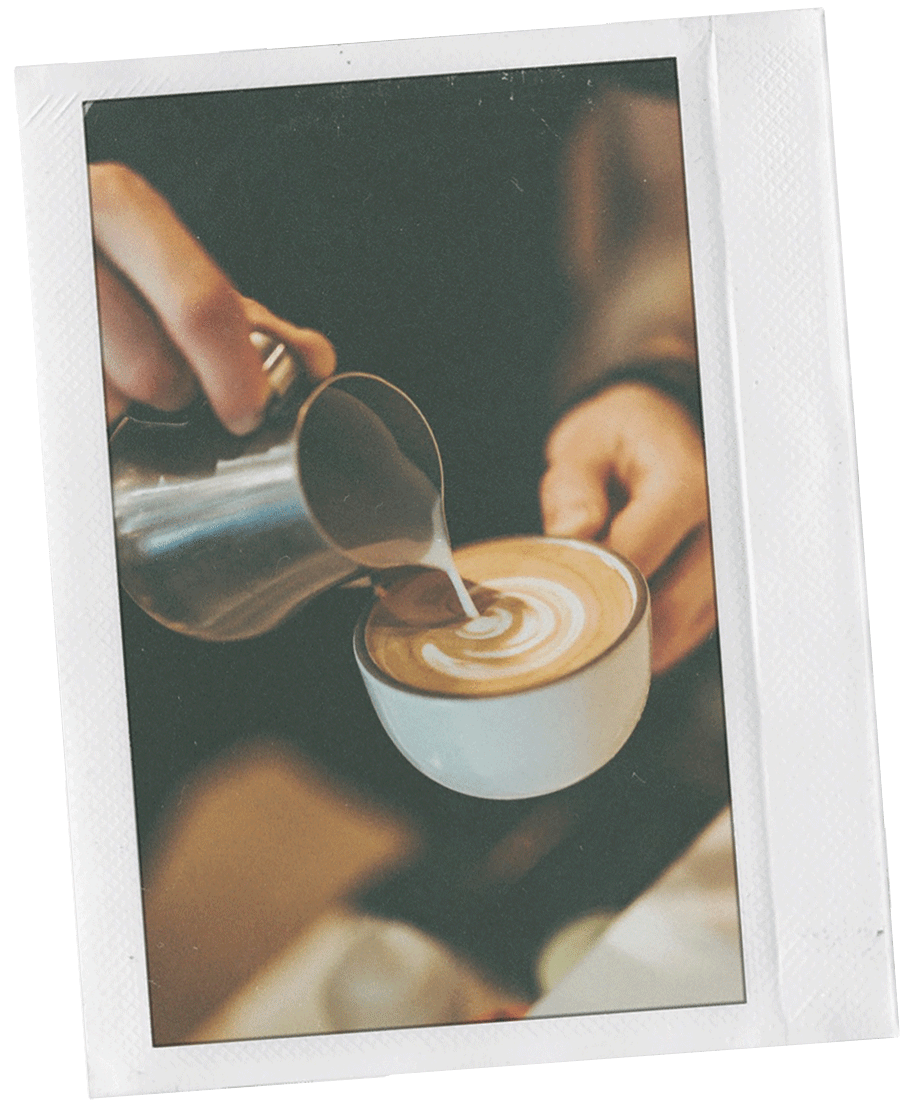

Brewing

From Chemex to Moka pots, Aeropress to drip: brewed coffee typically consists of a few components: coffee grounds, a filter of some sort, water, and an apparatus to make it in. While the methods vary, brewing coffee is an age-old practice dating back to 800 A.D.

Coffee Up

This is probably the best part. After your beans have made the long trip from harvesting to being roasted, ground up, and brewed, it’s finally time for those coffee beans to take on a whole new life: in your belly. For some, the drink remains controversial— concerns about caffeine content have prompted past attempts to ban coffee. But ultimately, the drink prevailed. Some researchers even say it’s good for you. We’ll go with that—because we need to.