By Eben Weiss / @bikesnobnyc

Bayswater is where New York City peters out into marshes, wetlands, and sandbars. A subsection of Far Rockaway, Bayswater is a peninsula off a peninsula that juts out into Jamaica Bay, and at low tide it seems like you can wade halfway to the runways of Kennedy Airport.

The neighborhood looks almost exactly the same today as it did when I grew up there (and probably not too different than when my father grew up there for that matter), though the two dominant features of my own childhood are now gone: the landfill with its perpetual cloud of seagulls, and the Twin Towers, which like the moon were always visible on the horizon and yet so impossibly far away as to be, for all practical purposes, totally abstract and completely unattainable.I was happy because I had a bicycle, and having a bicycle meant having freedom.

There was no through-traffic in Bayswater, which meant that we could play in the street pretty much all the time, and if the odd Chevy Caprice or AMC Pacer ambled along, the protocol was to call it out and scatter until it passed. Light traffic also meant we could ride our bicycles everywhere; well not everywhere, because I wasn’t allowed to ride to “town” where all the stores were and where the A train terminated. However, I was free to ride to all the places an elementary-school-aged kid might reasonably go in the course of a summer day, such as the sand dunes, and the rusted-out car, and my grandparents’ house, and of course the Mister Softee truck if we were within earshot of its thrillingly irritating jingle. The expanse of the Jamaica Bay shoreline was also fair game, and it offered up an endless supply of items to captivate the young mind, from horseshoe crabs to oyster middens to vast floating islands of plastic tampon applicators.

You’d say I was a happy kid. I was happy because I had a bicycle, and having a bicycle meant having freedom. Freedom doesn’t breed happy kids despite the dangers; it breeds happy kids because of the dangers. Our environment nurtures us, but it also teaches us, and it feeds us experiences the way the YouTube algorithm feeds us videos, only with infinitely more acuity.

The first bicycle thief I encountered appealed to my good nature.

I was riding up and down Norton Drive, enjoying the exhilarating sensation of speeding down the gentle slope that at the time seemed like a really big hill, when a kid I’d never met before asked me if he could try my bike. I had my misgivings, but I also still had one foot in the world of Sesame Street and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, so of course I knew all about the importance of sharing. “Sharing is a great way to make new friends!,” some puppet probably squawked ebulliently in my mind. And so I shared.

It’s a powerful moment when the idealism of PBS meets the harsh realities of the streets, and as my new friend rode wordlessly away I felt great shame, for only now did I realize how special my bike was, what a lavish and thoughtful gift my parents had given me, and how foolishly I’d just squandered it. As I hiked back up Norton Drive to report the theft to my mother, I felt like my feet were glued to the earth—not just because I was in trouble, but because as a bikeless kid I’d just been reduced to one of those flightless birds you see pathetically flopping around in an oil spill. Fortunately the universe granted me a reprieve, and after combing the neighborhood we found the bike lying unattended in front of somebody’s house. Thus I learned a lesson some people don’t until they rent their first apartment: never hand something over unless they hand you something first, and you’d better be prepared to never see what you handed over to them ever again.

It’s a powerful moment when the idealism of PBS meets the harsh realities of the streets.

Our environment may help shape us, but different environments shape us in different ways, and there were plenty of kids growing up just blocks from me who were in a totally different environment than my own.

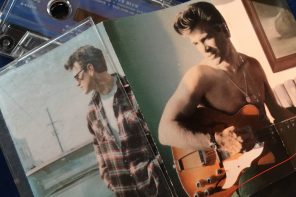

Their parents weren’t taking them to Woodmere Bicycle and buying them sweet Schwinn Scramblers with red Skyway Tuff Wheel II mags, or even any bikes at all. And while I may have known by then what it felt like to lose the power of flight, I could hardly conceive of never having been granted it in the first place, or of constantly being reminded of that by having to watch kids like me flit about in a state of bike-induced bliss. So, looking back now, I can only respect them for trying to seize those wings for themselves.

As we got older, my friends and I got used to kids trying to steal our bikes; it was just another facet of the childhood drama that was always playing itself out in the neighborhood, like touch football games that somehow took a left turn into fights. But even we were surprised when one day a group of older kids emerged from behind a parked Gran Torino. Unlike my first experience with bike theft there was no ambiguity here, and the stockings they were wearing on their heads broadcast their intentions with perfect clarity. They wanted our bikes, and they were going to take them by force.

My friends and I each sprinted in different directions. It was a sensation that later became familiar when I started racing BMX bikes: high-frequency fear, then the start gate dropping, then nothing mattering except going faster. Eventually I slowed down, and as the lactic acid cleared and I started to regain control of my thoughts, it occurred to me to wonder what had become of my companions. I circled back to our street, and everyone else’s flight had clearly followed the same trajectory, because we all converged around the Gran Torino at the same time. Breathlessly we each recounted our individual escapes, though if we reported it to any grown-ups I certainly can’t remember.