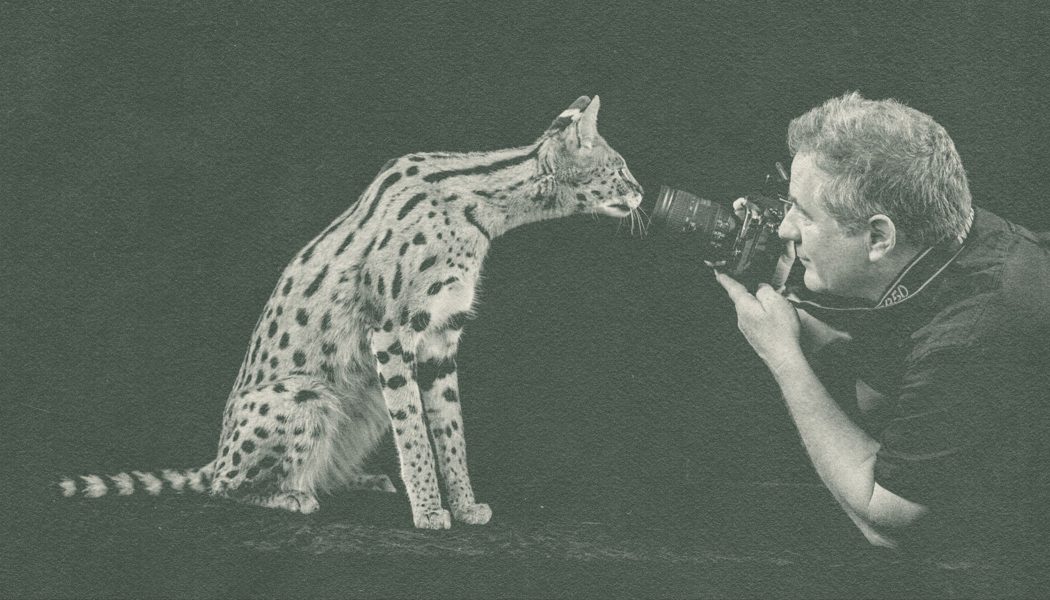

Conservationist & Photographer Donal Boyd With National Geographic Photographer Joel Sartore

Donal Boyd and Joel Sartore would seem to have an awful lot in common. Both photographers advocate for wildlife conservation through individual portraits of animals. Joel is on a mission, appropriately enough called Photo Ark, to photograph every species of animal living in captivity on the planet. While Joel brings the animals into controlled settings that give the project a consistent look—almost that of a catalog of the diversity of life on Earth—Donal’s visual advocacy for conservation takes place in the field, at the Erindi Private Game Reserve in Namibia, where he is the photographer in residence, and elsewhere. But both men are fighting to bring awareness to the fragility of the balance of nature and to protect endangered species.

Donal Boyd: Could you give a short background about your work as a National Geographic photographer and founder of the Photo Ark?

Joel Sartore: I’ve spent 25 years as a photographer for National Geographic—and guess I’ve got the stories and scars to prove it. These days my focus is on the National Geographic Photo Ark, the world’s largest collection of animal studio portraits. I am on a quest to document all of the approximately 15,000 species living in the world’s zoos, aquariums and wildlife sanctuaries. My goal is simple: to get the public to care and save species from extinction.

Donal: What species has been the most difficult to photograph and portray the importance of in the context of conservation from a visually engaging standpoint and why?

Joel: I stand by the fact that every species that has roamed, crawled, flown or swam this Earth is extremely important. Every species is visually engaging in its own way. That’s why I shoot on black and white backdrops for the Photo Ark—people are forced to take in the beauty of each animal. You’ll also notice that a small beetle is as big and large in my photos as a rhino. There are no size comparisons in these photos.

It’s tough when you’re photographing a species that is vanishing. I remember photographing Toughie, who was the last known living Rabbs’ fringe-limbed treefrog. Once he died, the species became extinct. He was small and brown, overlooked by the public nearly completely. Most folks still don’t know he existed. But telling his story is so important because we’re on track to lose so many more, and what happens to them will eventually happen to us. I just hope we realize that in time.

Donal: As a fellow photographer, I’m sure you share the feeling that it’s now more difficult than ever to stand out among the overwhelming ocean of imagery that people are bombarded with on a daily basis. Since you started the Photo Ark, has your approach to photography changed in order to adapt and compete with the increase of photographs online and rapidly shrinking attention spans?

Joel: I do see your point, but I actually am still hopeful because good stories, well told, get heard around the world. So I view this moment in time as actually a golden moment for conservation because we can reach so many people so quickly, all thanks to the web.

Before starting the Ark, I’d been working as a photographer for National Geographic for decades. My photos told stories about the plight of animals globally, but they didn’t really move the needle to save them. Enter the Photo Ark—social media is a perfect place for some of the more simplistic photos I’ve taken because they read so quickly. And as a result, some of the photos have actually made a difference to help save species. For example, Photo Ark coverage of the Florida grasshopper sparrow helped elevate government spending from $30,000 a year to document the bird’s demise to $1.2 million to fund a captive breeding program. That breeding program is a success today, thanks to the hard work of the researchers and breeding centers such as White Oak conservation center in Yulee, Florida. I’m very proud of that and fired up to do more going forward for other species in need.

Donal: I’ve explained a little bit about how Photo Ark has inspired me personally, but how do you aim to inspire other photographers globally through your visual approach and goals with the project?

Joel: Again, the need for good stories told well is there, now more than ever. I sure hope other shooters know that. And photography can expose environmental problems as nothing else can, which helps get people to care. This leads to action. And that’s a great thing.

Donal: There are probably a million photographs of lions out there on the internet and just as many of elephants, zebras, and some of the more popular well-known animals. Of all the people, professional or amateur, who go out on safari in Africa, or even for those who can only afford to venture out to their local parks or gardens on a backyard safari, how can anyone anywhere use their photography to share the narrative of the importance for protecting and restoring nature?

Joel: They say there’s nothing new under the sun, but there are a myriad of ways of interpreting what we see. So it really depends on an individual’s take on anything. I would add that it is not enough to show just pretty animals in an idyllic landscape. We must now show the threats to these creatures as well. Do we need to continue to show the beauty of nature? Absolutely. But if we want to make the world a better place, our photos need to inform readers of what’s really going on out there. The good news is that there are many publishers who want to publish stories on environmental issues.

Donal: What advice do you have for an emerging professional photographer or conservationist who is daunted by the thought of competing with the visuals of everyone else on the internet?

Joel: Getting a job and starting a career in photography is a bit rocky now, and I’m sorry to have to say it because photography is so dear to me. To be successful in photography in the current market, you must be the very best at what you do. Be passionate about every project you become involved in. Shoot the best photos anyone has ever seen of your subject.

It also helps tremendously to specialize. Become an expert in a certain species, or a part of the world or an issue in it—single-use plastics, keeping house cats indoors to save native birds, removing pesticides from lawn-care regimes, the list goes on and on. Become the “go-to” person on any issue you’re passionate about and you’ll be successful.

So, if you’re really excited about this, I say go for it. I still believe that those who are truly passionate will find a way to make a living doing what they love.

Donal: What is it really going to take to get everyone everywhere to actually make the changes we need to make in order to save the biodiversity of our planet in order to save ourselves?

Joel: I believe it goes deep into human nature itself. We are so successful as a species because we are resourceful, driven and never satisfied. I’m afraid this could be our undoing. But all of us can and should do things to help turn the tide. Though things may be bad, it’s now more important than ever to try and save the Earth. Nature has given us a handful of wake-up calls, we just need to make sure we’re listening. My motto: “Do the best you can with what you’ve got, right now.” You can do no more, but if others do the same, that may be enough.