Weapons of Mass Disgusting

Faced with a public sanitation crisis in 1939, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia acted with Churchillian decisiveness to strike a blow to the enemy of the people. That enemy was, well, the people. Specifically, the segment of the population who were just too damn lazy to discard their chewing gum in a trash receptacle after it lost its flavor. It’s as if, annoyed by the sudden lack of minty zing or fruity artificial juiciness, the chewer became so disgusted that he immediately spat his gum out onto the ground.

And things above ground were even worse. William Powell, the Assistant Commissioner of the Department of Sanitation, wrote in another memorandum that “during the summer, the gum that is thrown on the streets spreads over an area six times its size due to the heat on the pavement and cannot be washed up by cold water.” He estimated the number of careless gum chewers at one out of every five New Yorkers, which at that time would have amounted to 1.3 million people. The total cost per year was estimated in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Clearly, the City was at war.

On December 4, 1939, a day that will live in chewing gum infamy, La Guardia declared his war.

Faced with the calamity of weapons of mass disgusting threatening to take over the streets and literalize gum soles, La Guardia didn’t get tough with the scoundrels and go the law enforcement route, Guiliani-style. No, the Mayor did something strikingly modern to attack the problem. He crowdsourced the solution.

In a move that cities today struggling with the nuisance of errant dockless scooters such as Birds and Limes littering their sidewalks could learn something from, La Guardia called on the “enemy”—the public—to help create a campaign to educate, well, themselves. On December 4, 1939, a day that will live in chewing gum infamy, La Guardia declared his war. “This may seem like a trifling matter, but it costs the City of New York literally hundreds of thousands of dollars a year to remove gum from parks, streets and public places,” he wrote in announcing a campaign asking the public to submit slogans to help alleviate the problem. The beauty of his solution, of course, lay in the fact that the search for the solution was itself the solution.

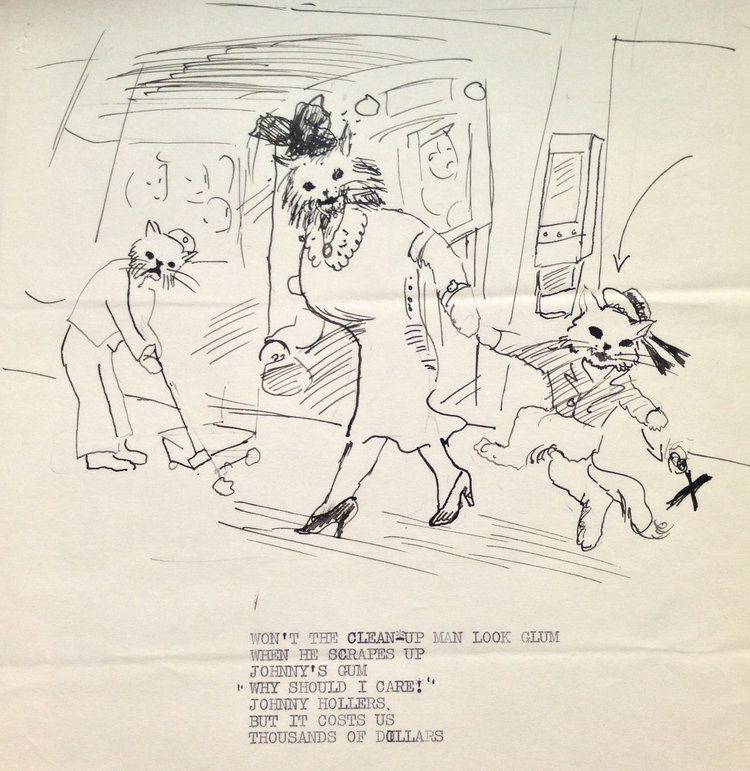

Frances Paelian of Spuyten Duyvil submitted a slightly disturbing comic of anthropomorphic cats cleaning up chewing gum from a subway platform.

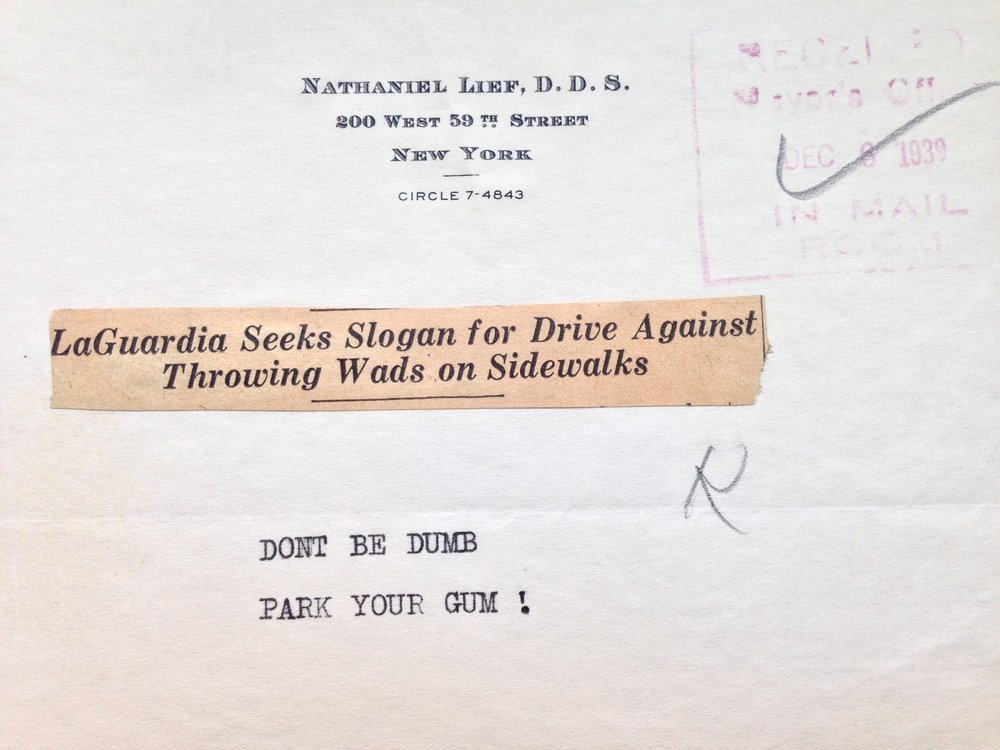

The social media of the day, the daily broadsheets and tabloids, ate it up. Not just in announcing the search but dutifully printing followups with the suggestions that came flooding in, such as “Gumby, Please,” “Chucking Chicle Chokes the Charm of our Choo-Choo Station,” and “Shoot the wad.”

The response of slogans, jingles, comics, treatises, and epic poems was somewhat staggering. Creativity poured from people from all walks of life from all the boroughs and Long Island. Nathaniel Leif, a midtown dentist, typed in all caps “Don’t be dumb, park your gum!” Edith Goldberg of Brooklyn went overwrought with a side of pun: “Wrap your gum. You, too, have a sole.” Frances Paelian of Spuyten Duyvil submitted a slightly disturbing comic of anthropomorphic cats cleaning up chewing gum from a subway platform. John Krol, a former employee of the Parks Department, handwrote: “Chew! But Don’t Strew Your Streets With Goo!”

John A. Roos of Riverside Drive got litigious and made sure that he included the disclaimer that he reserved to right to enter any future contest offering cash prizes with his, “Don’t be a bum; wrap used gum,” submission.

“Wrap your gum. You, too, have a sole.”

James A. O’Neill a member of the actual War Department based in Boston Army Base, bemoaned “the lack of evident good breeding,” that led to the epidemic and offered, among other spearmint-centric suggestions: “Let’s stick together on SPEARMINT. It’s too good a friend to walk on.”

Harry E. Henshaw from Lynbrook sent in: “Be popular—keep your gums up,” and, “Don’t make public walks targets for your gummary.”

Some even responded with acts of contrition and personal responsibility. John F. Klohr, purveyor of “Insurance of All Kinds,” expressed remorse for what he saw as his own part in the litter in a letter sent by airmail. To promote his insurance business, he’d given away as much as 60 sticks of gum a day for 15 years. He swore that henceforth he’d include a directive on proper disposal with each stick.

But Rose L. Beckman, a teacher at the Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn, won the day and the contest with the inevitable, “Don’t Gum Up the Works.”

Wrigley took this as an opportunity for leverage to re-negotiate vending rights on the Eighth Avenue Subway Line and outmaneuver the American Chicle Company.

This was not the only front Mayor La Guardia waged the war on. He took it straight to the manufacturers. He asked Wrigley, the American Chicle Company, Sweets Laboratories, Goudy Gum Co. and Beech-Nut all to support the campaign.

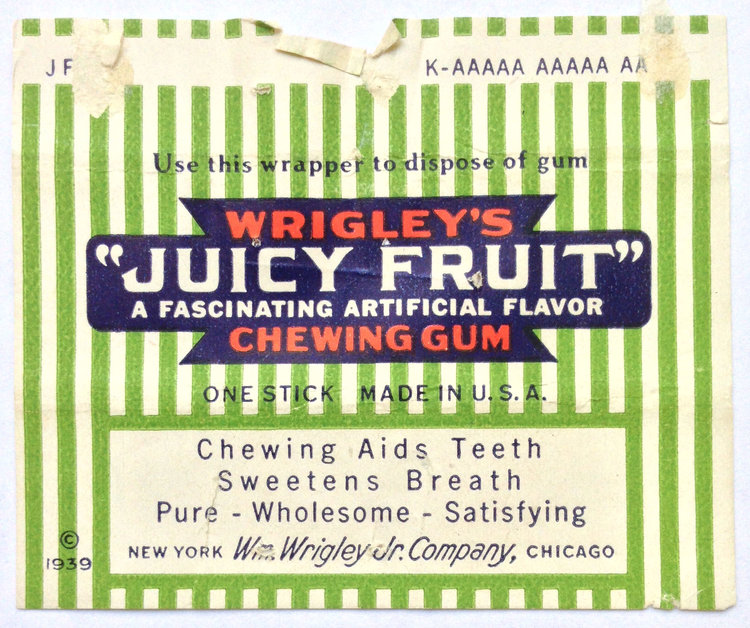

Philip K. Wrigley of the William Wrigley Jr. Company wrote back La Guardia expressing the Juicy Fruit maker’s embrace of the program, and pointed out that the company, for a great many years, had printed the “Use this wrapper to dispose of gum” on the wrapper for each stick, though he allowed that people probably don’t read the inside wrapper and that was why the message had not reached the chewer. Wrigley promised to change the next print run of ad cards for streetcars, buses and train cars. He also took it as an opportunity for leverage to re-negotiate vending rights on the Eighth Avenue Subway Line and outmaneuver the American Chicle Company that had those vending rights.

“Don’t Gum Up the Works.”

The American Chicle Company, for its part, agreed to add “Save this Wrapper for Disposal of Gum after Use” to all its wrappers. And though blissfully unaware of Philip K. Wrigley‘s skulduggery, maintained its rights to the Eighth Avenue Line.

The Chiclet Company though, really went above and beyond in its support calling in Frank Novak and the Stardusters, whose radio program it sponsored. Chiclets Rockefeller Plaza–based publicist David O. Alber wrote the Mayor with the good news: The Stardusters would sing a song about gum etiquette on the show to the tune of “Coming Through the Rye.”

The Goudy Gum Company had the most far-fetched, some might say delusional, response. For its movie theater clients, the company had been attempting to engineer some mutant, future gum. A.F. Delahunt, Goudy Gum’s treasurer wrote the Mayor: “This company has been experimenting with a formula that would make chewing gum free of stickiness.”

After less than two months the campaign wound down, and Mayor La Guardia and the City declared an end to the Chewing Gum Wars. Assistant Commissioner of Sanitation, Edward Nugent reported, “a decided improvement in this matter.” Hardly storming the beaches of Normandy, but a victory nonetheless.