No matter the medium, art allows personal expression, messages and meaning to be delivered by the artist in ways they may not feel comfortable or able to exhibit otherwise. For artist, photographer and Jacksonville, FL native Malcolm Jackson, his street photography goes way beyond a personal motive. Capturing life as it happens throughout the nation, Malcolm brings to light the stories of everyone in everyday life, highlighting those small moments that make us all human. Focusing on Black culture, Malcolm works to showcase the walks of life not everyone has a chance to celebrate through his lens. Snapping a few photos with Whalebone Magazine, Malcolm touched on the impact of his photography, why Jacksonville is so important, and the meaning and motive behind it all.

“The art of expression is different for everyone. Whether it be your medium, your meaning or your mission.”

Tell us how you got into photography, where you find your inspiration for your photos with such powerful and deep meanings and why this medium is such a powerful outlet for you.

For me photography is a way to record time—you’re able to freeze-frame time and the importance of that and how much power that really holds—portraying what happened in the past while also being a sight into what could be of the future.

It has a lot of power in that regard. It also has a way of connectivity that I think not too many other mediums have. Not to take away from other mediums at all. They all have their own way of connecting, but I believe there’s something about that freeze-frame right then in that instant that allows you to get a little closer with the piece.

Photography is more straightforward than some other art forms. It can be abstract, but it’s not as abstract directly. You aren’t trying to find something, the photograph is right there, plain and simple, and from there you pick out your own abstract ideas about what the photo is trying to say. It allows you to show many opinions. The saying “a picture is worth a thousand words,” is true because it’s all based upon the opinion of one’s perspective and it’s nothing that’s definitive.

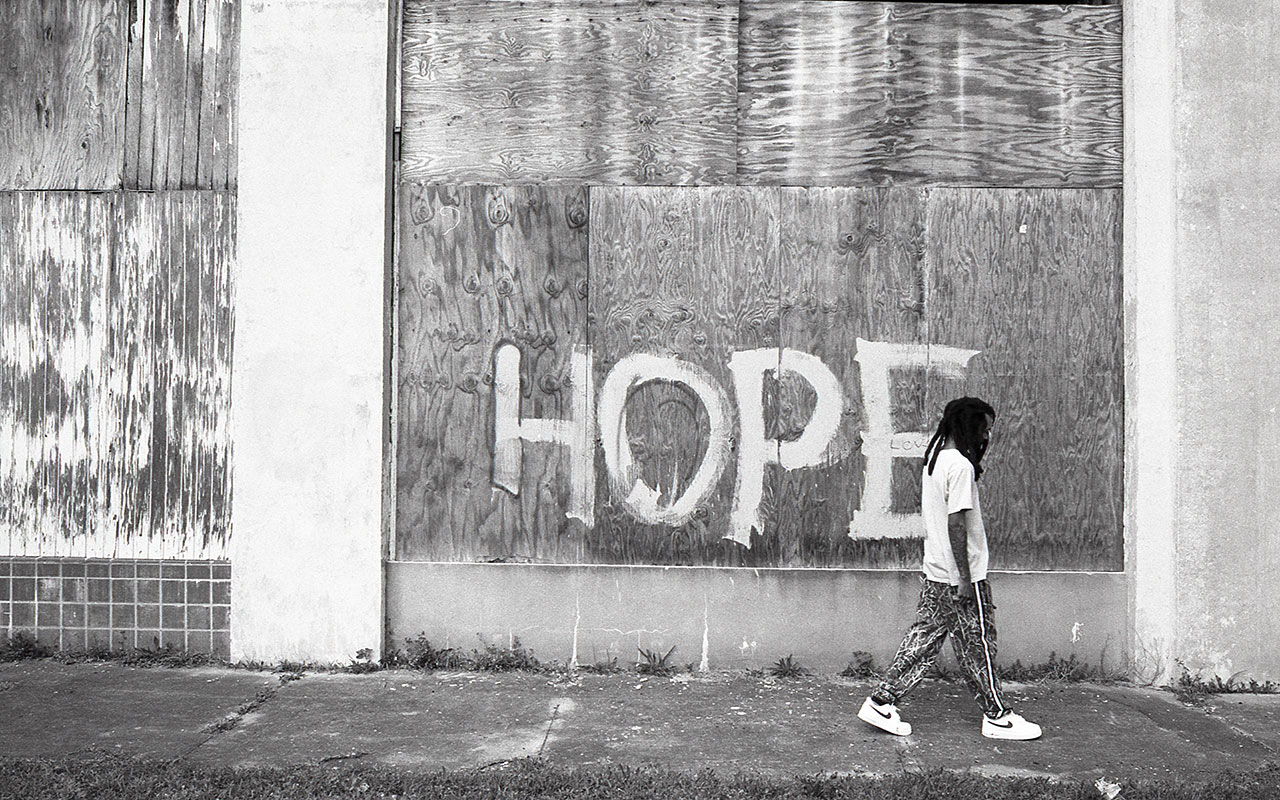

And I think the true essence of street photography is really admiring the beauty of just living life. Period.

All those things connected together show why it’s so important and so powerful. Outside of painting a portrait, a photograph is probably the most coveted thing you’ll have in your home. What you get with photography is very personal which you can’t get with many things in this world.

I’m inspired by the world that I’m around. In my line of work as a street photographer, I’m just documenting what I see outside. And I think the true essence of street photography is really admiring the beauty of just living life. Period. There’s nothing that has to be over the top, it’s just literally documenting life as it is. The beauty and the flaws that create this beautiful thing.

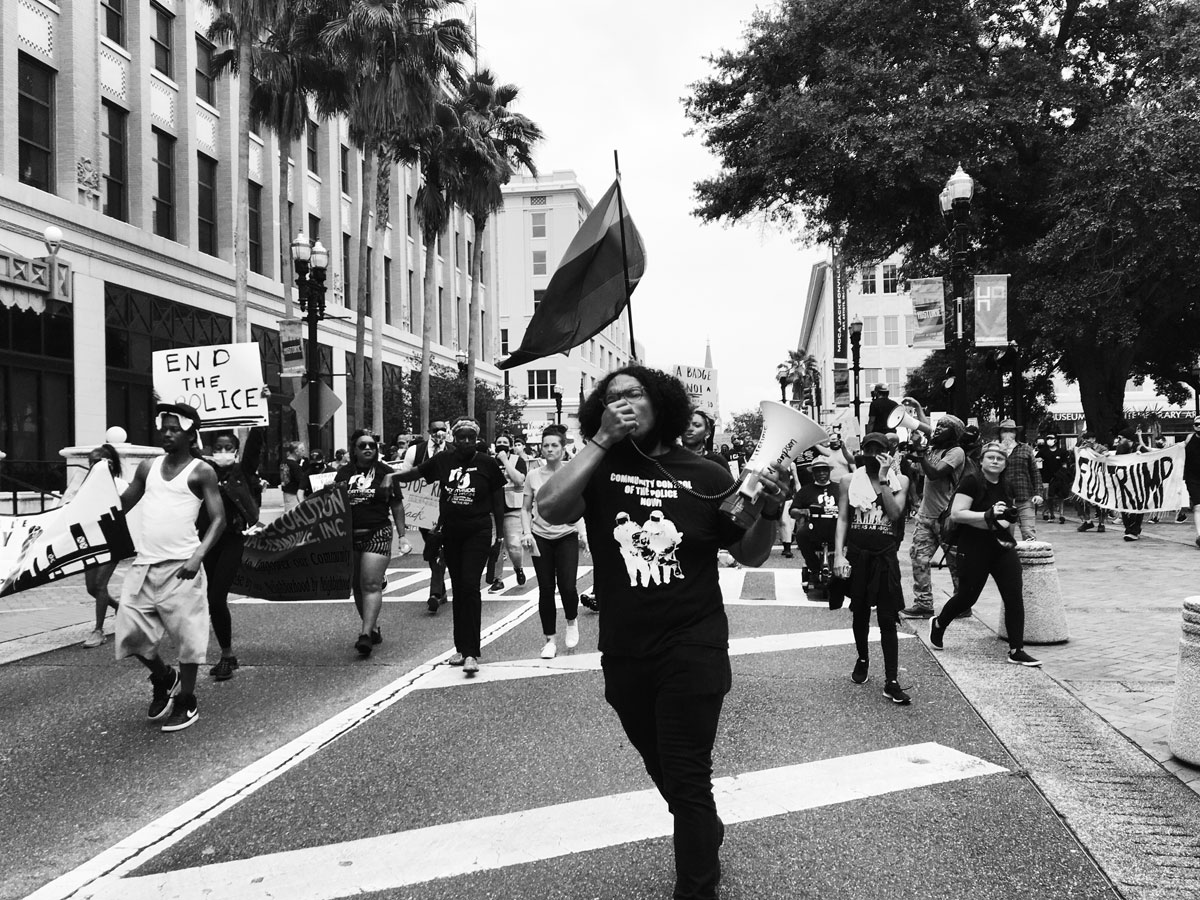

Within that, I do have an emphasis on African American culture. That’s where I come from and in today’s time it’s been brought up to the light more correctly, but it’s still not done right or it’s been exploited in ways our community hasn’t been able to recuperate from. It’s never been done respectfully until recently. I try to use my camera to try and help those things out.

I had a very millennial way of getting into photography. I grew up running track and that was really the only thing I saw myself doing. Once I got to high school I had some D1 offers that were getting looked at, but I got a bunch of injuries that started having me sidelined, so I was just watching it go down the drain. At that point, I really didn’t see anything else in my life.

When I was younger, my uncle taught me how to use a camera and how to shoot cars. I thought it was fun but never really put that much emphasis on it because track and field were what I always did.

Once I finally put the spikes down, I fell off into a deep depression. Right at that point, I picked up a little cell phone camera and went with my best friend growing up and his parents on a trip to DC. We went to all the Smithsonians and I remember taking a bunch of pictures at the Light Air and Space Museum. I really enjoyed taking those pictures and from that point had the bug, or the seed that was planted had finally started to grow.

I used it as a way to cope with my depression as a way to make me feel better—it became a sort of therapy. It wasn’t until I was 20, 21 years old that I started to actually study photography via social media, Tumblr, YouTube.

Once I started taking photography more seriously and studying photography, Gordon Parks was the first person I went to. After going through his work and reading one of his interviews, I heard him say he uses his camera as a weapon to fight race poverty in social-economic systems in America, and that hit me like a ton of bricks—that is exactly what I wanted to do and how I want to move and operate. So I asked myself, how can I use my camera for more than just taking pictures of flowers, but how can I make those flowers have meaning and context. I just saw so much of myself in what he was doing.

I also pull a lot of inspiration from Robert Frank. I learned more of the basics of street photography through Robert’s work. I also learned about the beauty of imperfections. A lot of photography is always looked at for being super polished, whereas I’ve always preferred the unpolished. I’m more of a rough around the edges kind of guy, so I prefer that in my work. The composition may be there, but it may not be fully in focus or as sharp, but the emotion is there.

My friend introduced me to Roy DeCarava, a black photographer living in Harlem up in the 40s and he was the first artist to get a fellowship at the Guggenheim. That went unknown for a long time, but a lot of his work was so quiet and basic but it was so powerful because he was documenting Harlem. That’s when I got the idea of taking the lessons—I’ve learned from all three of these guys and applying that to Jacksonville and wherever I go. Give Jacksonville that purpose of seeing themselves differently through the work of a more realistic, honest way.

There wasn’t much Black life being documented in Jacksonville, so these kids don’t see themselves in anything. With that in mind, it allowed me to document where I am for the purpose of trying to understand my world better and to show my world, with an emphasis on my people in particular, that we need to be celebrated and we can have those same images just like everybody else.

It was a tough thing to take on but I just felt if nobody else is doing it, then obviously we need to do it. It’s just always been a deeper purpose that will continue to have meaning way after I’m gone.

Describe to us why Jacksonville is such a special place to you and why showing the intimacy of life in the city is such a prominent component of your work.

Jacksonville has always been the red-headed stepchild and I’ve never understood why. But I’ve been blessed to have very deep roots in Jacksonville and through that, I’ve learned a lot about the true history of Jacksonville and how historically important this city is to the history of this country. From James and John Weldon Johnson who gave us “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which was originally a letter for Abraham Lincoln that became the African American National Anthem to the first ever live recording of the blues. So if it wasn’t for Jacksonville, there’s no telling when we would’ve heard the blues as a musical genre.

There’s so much history and especially Black history that built Jacksonville into what it is today but it’s never made the national press. It’s always been more of a the-bad-news-travels-fast type of place, where the bad things that happen here always manage to find themselves being talked about as opposed to all the millions of good things. There’s a certain spirit that’s here that a lot of places don’t have. It’s a very blue-collar place, but very, very true-spirited and very loyal people that come from this place.

It’s always been misunderstood and I’ve felt that the only way it can be done right is by having people that are really from here tell the true story and the true nature of what makes Jacksonville Jacksonville. It’s not a place that is designed to be an Atlanta or some of the bigger regional powers. It’s not meant to be that place and once you accept what it is, it makes it that much better and bigger.

I love it in every inch of my bones. I’ve had plenty of opportunities to leave, but I’ve decided to stay here and just travel. You can’t beat the spirit that comes from this place. There is so much opportunity here that has been untapped, even from a local perspective.

I do work all over the world, but every gig that I’ve done in my freelance career is all because of the work I’ve done in Jacksonville.

It has found ways to keep me here and I enjoy staying here to give back to the next generation of Jacksons that come through this place and help them build a better Jacksonville creatively and culturally that will stand the test of time.

What does shedding light on the realities of life for different people in different places teach you? How has this shaped you?

When you are able to photograph somebody, you’re catching them at their most vulnerable point. Anytime you’re facing the camera at someone there’s that one millisecond where there’s no safety, so you’re catching them at their purest. At that moment you can find out a lot about somebody and how they operate. And with that, I have learned a lot about not judging people and never judging a book by its cover. It teaches being more humble about what you do and what you have and appreciating the position that you’re in.

…it’s more just learning more about how to be a better person, learning how to maneuver in this world better, understanding the importance of what I’m doing in regards to younger generations of people.

I may have a little fame, but I don’t look at myself like that at all and I just try to keep that same approach with my subjects. They feel that it’s always a mutual thing—I’m not here to photograph you for the sake of photographing you—it’s for the purpose and for the intent of bettering all of us. It’s not a profitability thing, it’s more just learning more about how to be a better person, learning how to maneuver in this world better, understanding the importance of what I’m doing in regards to younger generations of people.

Doing that is being a living martyr in some cases. Where much of that resource wasn’t here so I am able to provide something to give back, whether it’s advice or being in these rooms where these people dream of being. I’m able to be there, I’m able to make the mistakes and help somebody else when they get to that point of being better. I tell a lot of young photographers that I’m doing this so when they get to this position, they will be able to make more money than what I made. People often ask why I do this, and it’s for me to pass it down, then for the next generation to pass it down and pass it down as photographers and just culturally for the city to give people another chance.

You could start off with taking 45 photos, but within that, you could’ve had a conversation about anything, even cheeseburgers, but that’s what could’ve provoked the expression that you needed to make someone happy. Sometimes that’s all it takes.

You don’t have to play these sports or other things you’d expect to be successful or for fulfillment. That’s how I try to view it and approach it. Try to understand my place in that and try to understand my importance as a storyteller and being a keeper of stories within those frames. I’ve learned a lot about cherishing those stories and when I’m photographing, I don’t like to just snap snap snap, and I’m not necessarily a talker, but I like to live in the moment with my subject just then and there. You can take a thousand photos on a digital camera but you don’t have a real experience, you only have the pictures. I think photographs are a lot deeper than that and there are differences between photographs and pictures to me. It’s more so the beauty of the process than the beauty of the finished product. While the finished product is important, the beauty of how you got there allows you to have more options once you get to that point. You could start off with taking 45 photos, but within that, you could’ve had a conversation about anything, even cheeseburgers, but that’s what could’ve provoked the expression that you needed to make someone happy. Sometimes that’s all it takes.

When someone looks at your images or a specific exhibition, what do you want people to walk away from your photos thinking about and/or having learned?

I just want people to take away that honest viewpoint in what I’m doing or what I call a small snapshot of America. It’s always been the gist—just being an honest look at life for what it is and simply enjoying it. I think 2020 has made everyone appreciate that a little more especially. Something as simple as a photo of two girls on a swing can hold so much more power now because it’s simply about living. Just the honesty and truth and life lessons in swinging. So I just like to have an honest and truthful viewpoint. If I can teach a life lesson in the work, I’m here for that.

I also have a responsibility as a Black photographer, and there is a certain weight that is added to that because I’m not just photographing for myself, but for a community—hell, a nation. There’s so much more to it, so taking that approach also and carrying that all at once.