The Lemonade Stand Winners of WISSP on providing access to basic needs and economic stability in Malawi

About a year ago, Whalebone put on a little something called The Lemonade Stand. A nice endeavor that encouraged anyone with a side hustle or passion project to let us know what they were working on so we could connect them with resources, mentors and materials needed to make whatever they pitched more than just something on the side. With a panel of judges from various leadership positions in various industries including Mark Groves, Bethany Yellowtail, Eduardo Garcia, Rhona Harper and Kat Hantas, and a whole lot of deliberation, the gals from The Pennington School in New Jersey in WISSP—Women in STEM Solving Problems—were chosen as the winners for their Hybrid Sanitary Napkin for Economic Change. And here’s why.

This group of women in STEM has worked endlessly to make a difference in more ways than one for refugee women located in Dzaleka, Malawi. With insufficient access to resources, the girls at The Pennington School in New Jersey decided to put their minds together to not only provide reliable resources for menstrual care for women but with this also jobs, economic structure and hope for permanent and positive change for the community.

To learn more, Whalebone chatted with three of the ladies behind WISSP—Susan Wirsig, Lexi Lepold, and Julia McDougall—to walk us through their process of deciding to make the world a better place for others. And not just for a short period of time, but with the idea of long-term self-sufficiency in mind for women who need it most.

Whalebone: Set the scene for us: Tell us about the community you’re working with in Malawi.

Susan: We are working with a refugee camp 55km from Lilongwe, Malawi, which is home to 55,000 refugees who come mostly from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi, Rwanda, and Mozambique often fleeing civil unrest or a natural disaster. While Dzaleka provides a safe place for these displaced people, once they arrive at the camp, they are not free to come and go or participate in the formal economy. As a result, the people live in extreme poverty with limited food and water and live in congested housing and an overcrowded education system. Teen girls, in particular, are impacted by these limiting conditions, specifically due to the lack of resources available to manage menstruation.

Lexi: It was really shocking to learn that menstruating teens at the camp miss 50 days of school per year, which amounts to 300 days for the 6-years of menstruating school years. As you can imagine, this level of absenteeism is just enough to pull the girls away from their academic goals and towards domestic responsibilities, which significantly impacts their economic opportunities.

Explain what you did to solve this problem. Explain to us the steps taken from start to finish.

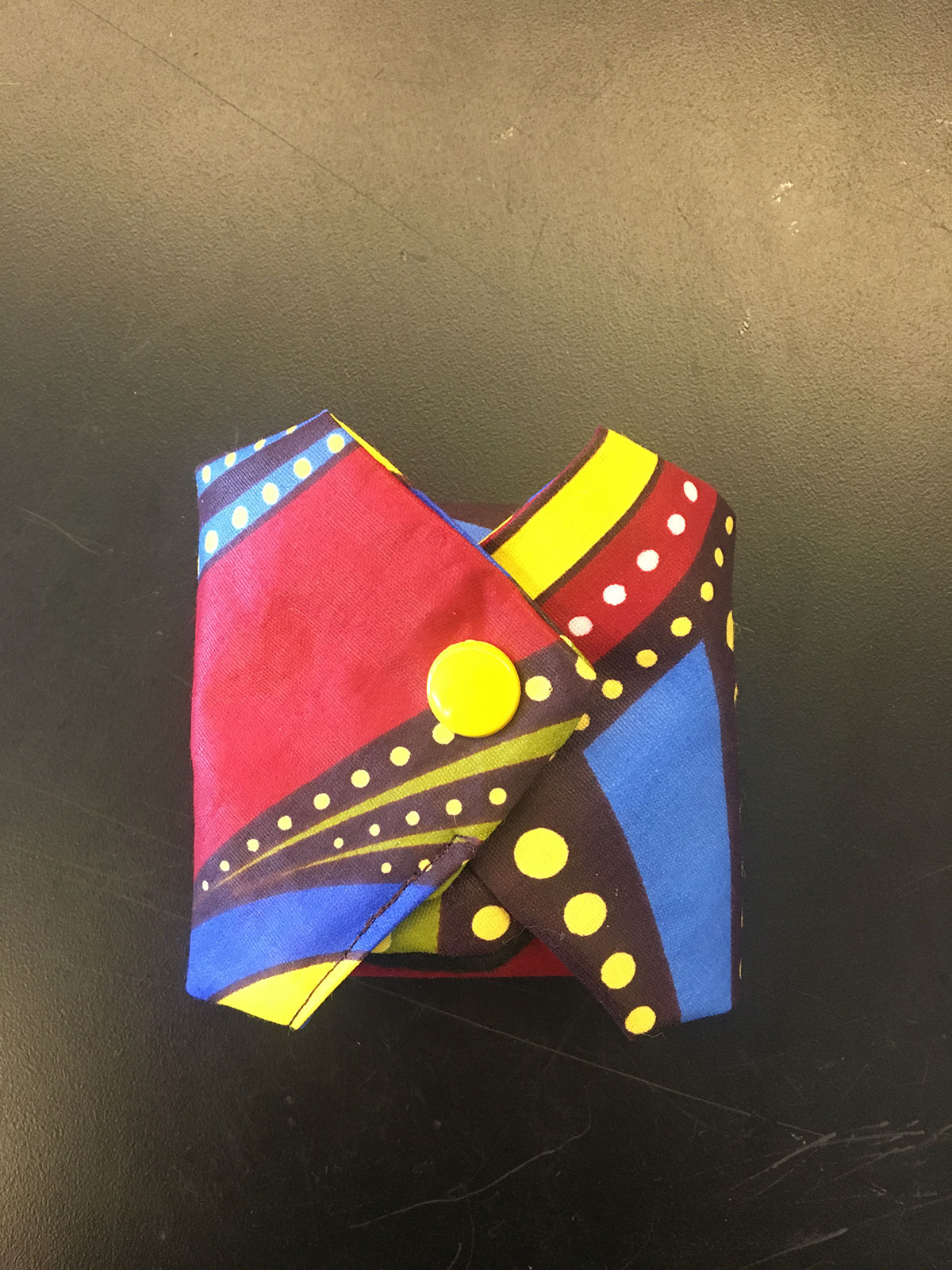

Susan: The passion the girls brought to solving this problem was incredible. In the fall of 2019, the Pennington girls met regularly to create a hybrid pad that was part reusable and part disposable, which would provide a period solution for girls living in a low-water, low-resource community. To begin the design process, they tested out reusable pads already on the market, and in the process, considered how they could be redesigned to also be partly disposable. They tracked how many pads were used each day, and how much water was used for cleaning. They had an idea to create a design that utilized a disposable component, and after testing the product with the members of the club, they decided that the hybrid pad was ready to be tested by girls living at Dzaleka. They mailed the pads to the girls in the camp, and then met them on Zoom to learn about their experiences.

Lexi: It was really interesting to hear from the refugee teens how the pad worked for them. They told us the hybrid pad design was a game changer—it provided secure protection, and due to the partly disposable component, it required less water for cleaning while reducing the disposable waste at the camp.

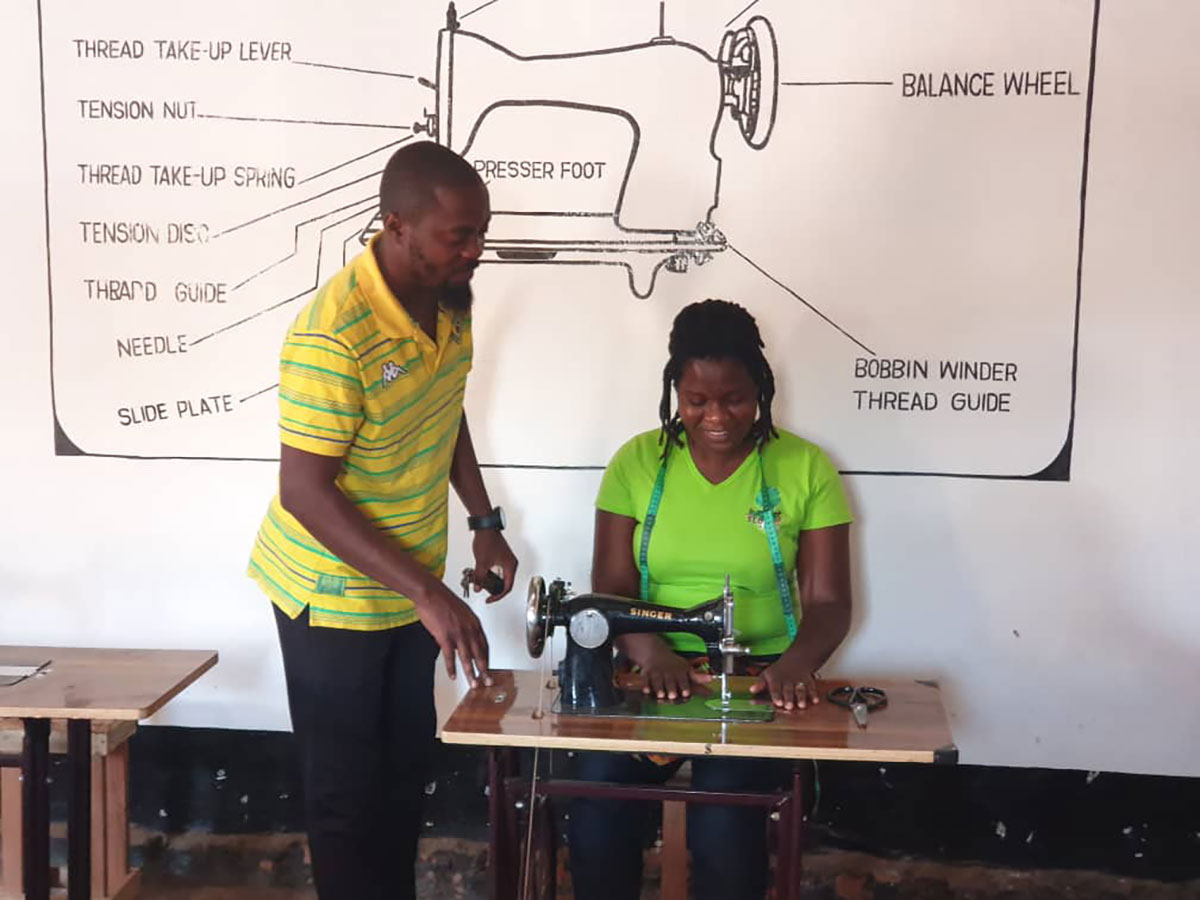

Julia: We felt proud of our product and the small impact we made, but we didn’t want to stop there. We decided to package the product into a larger initiative that gave the materials, tools, sewing and business training to displaced women to produce the hybrid pad as a source of income. We thought then the pad would become more than a means to helping girls stay in school, it would also become a route for women to learn a skill and earn a living. This being an opportunity for more women to be part of the economy, support their families, and to have an education.

It sounds like you wanted to set up a mini-economic infrastructure at the camp that would help the teen girls. Was that a smooth process?

Susan: Everything was going great with the project. By January 2022, we had developed a relationship with a local tailoring school and 18 teen refugee teens were trained on how to sew the pads. The teen girls made 1,000 pads at Dzaleka. But, due to the stigma surrounding menstruation, the refugee teens were reluctant to sell the private product at the market—which is culturally considered a male job.

Lexi: At this point, we were a little discouraged but we decided to adopt an Avon model and created materials that the refugee teens could use to sell the product on their social media platforms, thereby eliminating the public selling of the product; however, sales were slow. To reach sales targets, we knew we needed to find a culturally acceptable way to move the product.

We can imagine the importance of considering the culture in the design of the solution, which is a key component of the Human Centered Design process you used. What did you do to solve the distribution problem?

Susan: First, we began researching how teen girls in Malawi access period products. We learned that there are many NGOs that provide period products and menstruation education to teen girls all over Africa. We reached out to two of these NGOs to see if they’d test the product with their constituents and gain feedback on how it works for them.

Julia: The feedback we got was another point of validation for us. The teen girls told us that the pads they normally use are of low quality, expensive, and have a significant negative environmental impact. The WISSP pad, however, was comfortable, reliable, and sustainable.

Lexi: And as an added bonus, the NGOs expressed interest in teaching their girls how to make the WISSP pad locally, thereby growing sustainable skills within their communities.

How have you established an ongoing economic infrastructure for this process of manufacturing and distribution? What does the future hold for the WISSP pad? Where do you want to take the product from here?

Susan: Currently we are in the process of scaling up our sustainable model. I believe there is an opportunity for the WISSP pad to become a major player in the Malawian menstrual hygiene market by providing a sustainable period product with economic payoffs for Malawian teen girls. We need to connect with more NGOs, and further develop our training kit so it is easy for NGOs to teach their constituents how to make the WISSP pad locally.

Lexi: And as we develop our model, we will continue to support the Dzaleka pad production which provides a period solution and economic infrastructure to displaced women living in a marginalized community.

What is the most impactful thing you took away from this experience?

Susan: For me, a 30-year veteran teacher, it is amazing to see the impact this project has had on my students. I’ve seen their skills and confidence grow as they use the HCD to solve real world problems. I truly believe that they will carry this experience with them in the future and become empathetic problem solvers.

Lexi: Being a part of this project from the very beginning has been a truly remarkable experience. Watching all of our innovative and creative work unfold and seeing the impact it has had on those who menstruate, both in Dzaleka and elsewhere in Malawi, has been incredibly meaningful on a personal level and a career level. It has made me aware of such a common but overlooked problem that exists all over the world, while also providing me with professional experiences and skills that are beneficial to my academics and future career.

Julia: This project has changed my worldview and has shown me the impact that one project can have. It has grown to be a passion project and something that I care about so deeply that it has changed my career trajectory. Working on this project has made me a more empathetic and compassionate person as it ignites my desire to create sustainable and culturally conscious change.