Legendary guitarist Ry Cooder talks with his son, Joachim Cooder, about his new album

@rycooderofficial x @joachimcooder

Joachim Cooder first heard the songs of Uncle Dave Macon (no relation, that’s just the stage name of David Harrison Macon, an influential figure in folk and country music) as a boy when his father Ry would play them on the banjo. Now an accomplished songwriter and multi-instrumentalist in his own right, Joachim has recently released Over That Road I’m Bound, his own interpretations of Uncle Dave’s songs. “My dad would play the banjo a lot and he would sing a couple of these tunes,” says Joachim. “I gathered from him, he had heard Pete Seeger play them and that Seeger was a big proponent of Uncle Dave’s music. There was one song in particular, ‘Morning Blues,’ that I remember being drawn to as a little boy.”

After Joachim’s daughter Paloma was born, the refrain of the old early American folk came back around. “I would bring my daughter over to my parents’ house and my dad would play the banjo, and that’s when I heard ‘Morning Blues’ again. I said, ‘ Wait, what is that song?’” Joachim had an electric mbira, a type of African string instrument that influenced the development of the banjo, on hand. “There was something very modal about how my dad was playing that one song—or about banjo music in general—so I picked up the mbira and just started playing with him.” The kernel of the Over That Road album was born, and Joaquim began tinkering with other Uncle Dave songs, listening to them with Paloma, who became a sort of director of the project, and playing them for her. “She insisted upon certain songs and we would listen to the same ones over and over again, learning the songs. Then I started changing the lyrics around with her in mind.” Father and son sat down to talk about, among other things, Uncle Dave, Banjo Bill and what Paloma thinks of all of it.

Joachim Cooder: I’ve been noticing that in [the] interviews [I’ve done for this album], a lot of people have said that I’m carrying on the tradition of re-interpreting old-time music the way you did in your records in the ’70s.

Ry Cooder: Yes. Well, I see why they would think that. And I see that they would quickly think that because time has gone on, and I can see why they might think at first that you’re doing something that might seem to be what I did, but there’s one big difference. In my point of view, it’s that when I was younger, let’s say 12 or 13, what I was trying to do was to learn how to play like the records. I heard banjo. Bluegrass. I said, “I’m going to learn to do that.”

Not to copy somebody—you don’t wanna play exactly like Earl Scruggs note-for-note. I never wanted to do that, but just get to where I could play that type of music, which was great because later on, when I was recording, if I felt I needed some skills, I knew I could play blues and I understood open tunings. Therefore, if I want to play a Blind Blake song, I knew exactly what those notes were. So that I could play it, and I could please myself and then hear it back in the recording studio. That’s a key difference because you don’t do that. I knew you never wanted to be somebody who studied source materials, with the idea that you were gonna replicate Uncle Dave Macon on the array mbira.

Joachim: Right.

Ry: That’s not what you do by any means. It’s interpretive, of course, but it’s completely unexampled and completely creative and new. New being a kind of a silly word, but I mean different. A way to re-envision. But somebody like me or somebody like Dan Gellert and Rayna Gellert, for that matter, on fiddle, we learned the original because we liked it. So, when you hear something you like, you want to do it, too. That’s all. I wanted to do it well. But you don’t necessarily stop there. Because I always knew if I was gonna record, there would be very little point in doing all that music, whether it was Charlie Poole or Lead Belly or Blind Blake or somebody, note-for-note wouldn’t work because they already did it, so it was already done to perfection. If you love the record so much, you’re so impressed with this—so imprinted by it—then you had to do something about it. But what was that gonna be? That was gonna be to develop it a little and see how far you could go or see what sounded good. Do you like the playback? Go in the booth and listen. Got to record. Fantastic. Did I succeed? I don’t know. Sometimes I thought the ideas were good, the execution was questionable. [Both laugh] But what you did with this record and have been doing for quite some time, is to completely recast the whole entire thing.

Joachim: I guess, ’cause the mbira is not the original instrument that it was played on…

Ry: Right. It’s a radically different instrument.

Joachim: So, therefore, even if I set out to see if I can play a banjo pattern on this thing, it still won’t come out exact. Even if you think you’re going to try and do something exact, it will never be exact.

Ry: No, never be.

Joachim: So it just sorta—wanders off real fast.

Ry: Right. Then you start wandering off into some other territory, unknown, uncharted, no maps when you go about it that way.

Joachim: And then a lot of people always ask, you know, why did you choose Uncle Dave? But I think his songs at their core are really, really good songs. They’re so catchy. They’re not obscure or hard to see your way into.

Ry: That’s right.

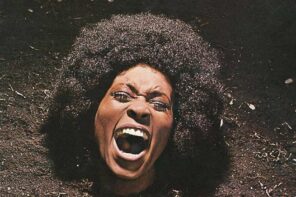

Photo by Amanda Charchian

Joachim: I put on the Banjo Bill Cornett that you sent and Paloma [his daughter] ran into the kitchen and then she was like, “I don’t like this Uncle Dave song.” [laughs] And I was like, well, “It’s not Uncle Dave,” but I could see why she thought that.

Ry: Sure.

Joachim: It’s just not that it’s darker, but it’s just so obscure.

Ry: Yeah. It’s completely obscure, almost alien to our ears. He’s the most far-out guy on banjo in old-time country I think I’ve ever heard.

Joachim: Yeah.

Ry: The way he plays, the sound that he gets with his voice, it’s like Banjo Bill is from Mars or Venus or someplace.

I cannot imagine. I don’t know the tunings, I can’t figure out how to do it, I can’t visualize how he played. Uncle Dave’s an open book. That’s why he was so popular, probably. People really responded. They really liked what he did. He was a great entertainer, he was a showman. He danced while he played, he told jokes, a medicine show. Great songs too, of course.

I can’t figure out how to do it, I can’t visualize how he played.

Joachim: Since we did the thing at Skirball, I’ve been working on “Plank Road.” And so I was sitting around at our friend’s house and I’ve left my acoustic mbira there so it’s there when I go. And I start playing it and I swear, 15, 20 minutes later, I’m hearing people hum it just from me working on it. It catches. It’s a bit like a pop song you know.

Ry: Yes, yes.

Joachim: Bom-da-duh-mon-woh [singing a melody] it’s just so good.

Ry: Really good.

Joachim: It’s such a hit.

Ry: It’s a hit. He was a hit. They say he was the first big superstar of the Grand Ole Opry. And he was. He was around for a long time. You know, he got to be a very old man in the business. Those songs still sound great to us today. You will never think that the songs are 80, 90, 100 years old.

Joachim: When I dropped off Paloma the other day and her friend, Penny, who’s English, one of the days when we were all supposed to be working at Village Playgarden—or one parent would work and the other parent would be watching the kids—and so all the moms that were there I gave a CD to.

Ry: Oh, wow!

Joachim: And, [laughs] and then Rose who is Irish. And so she loved the Uncle Dave songs because she thought that they felt Irish to her.

Ry: Sure. Absolutely.

Joachim: And I said, yeah, you know, what is the lineage of that music? Is that a thing? That’s a direct thing?

Ry: Oh yes. Of course, everybody agrees that Scotch-Irish-English background is what American country music is.

All of those people in Appalachia and the southern States, that’s where they came from. That’s where their ancestors came from. And the music is a very strong thread there. And Uncle Dave was a 19th-century man. I mean he learned and heard music then. I forget his birth year, but he grew up and at that point, he wasn’t too far distant from the immigration. Especially the Irish who kept coming. They never stopped, all those dances. Paddy Moloney [founder of the Irish band The Chieftains] once ran it down to me, naming a bunch of American country tunes from that era and naming the Irish original song. “Oh, we used to call that such and such,” he would say, “That it’s not ‘Plank Road.’ It’s called something else.”

Joachim: Right, and “Rabbit in the Pea Patch” that, duh-doot-da-da-duh-doo-do-da-da [singing]. That. You can just see them.

Ry: Oh yeah. The tin whistle and all that. So I’m sure your Irish mom friend—

Joachim: Rose. She wanted to send it to her mom back in—

Ry: Oh yeah, back in the old country.

Joachim: Yeah. And then little Penny ran up and said, “Joachim,” she has her little accent [doing a proper English accent], “Your music is the only thing I want to listen to now.” [laughs] With her little tiny English accent.

Ry: There you go, young and old alike. That’s hard to get. We’re so fragmented now as a society into these tribal and class and age structures that this record, you know, your record cuts across all that 110 percent. Oh yeah. Everybody’s gonna be happy. No long faces.

Photo by Paul Natkin

Joachim: Yeah. I mean they, and these are also moms who don’t want to bombard their kids with grotesqueries.

Ry: That’s for sure, which there are many of. Yeah. It’s perfectly soothing. Like a friendly presence in a nervous world. I listened to it driving out today in the car, you know, all the way.

Joachim: Oh, yeah?

Ry: It takes the whole record from home to here. And that freeway journey, as awful as it is, you just don’t care. I got going a little too fast on “Rabbit in the Pea Patch” though. I hit the 110 interchange and almost got in a wreck, but I said, “Whoa! Back off.” [Laughs] mm-hmm. Paloma sings, “Get that dog and let’s go huntin’,” she says. Thank god it says, “Get the rabbit out of town,” doesn’t say shoot the rabbit. That’s nice. We’re happy about it.