Shooting the shit with Laura June Kirsch

Once upon a time there was an island called Manhattan, but probably more often you were in Brooklyn. Just breathing the air at night when you stepped out for a smoke under an awning might fill with hope and optimism. Then you might head back into a crowded, sweaty club where strangers were making out in corners and everyone was shouting to be heard above the euphoria and hugging each other. Sure, the once upon a time seems like a fairytale ago, and in some ways it was that long ago that much time has passed—long enough ago that not everyone had a camera in their pocket and a signature pose at the ready, but close enough that we can see ourselves in images from that time still.

Just after 11 p.m. on November 4, 2008, the atmosphere changed—like a crack opened up in the sky and a thunderbolt hit the island of Manhattan. At a loft party in SoHo, drunk interns (and Jesse Jackson on the TV) shed tears of joy, Sarah Palin cutouts crowd-surfed and the words “Proud American” no longer conjured images of a guy in a Rangers jersey sitting on his couch watching Nascar and eating junk food. For a few brief shining moments, it was so.

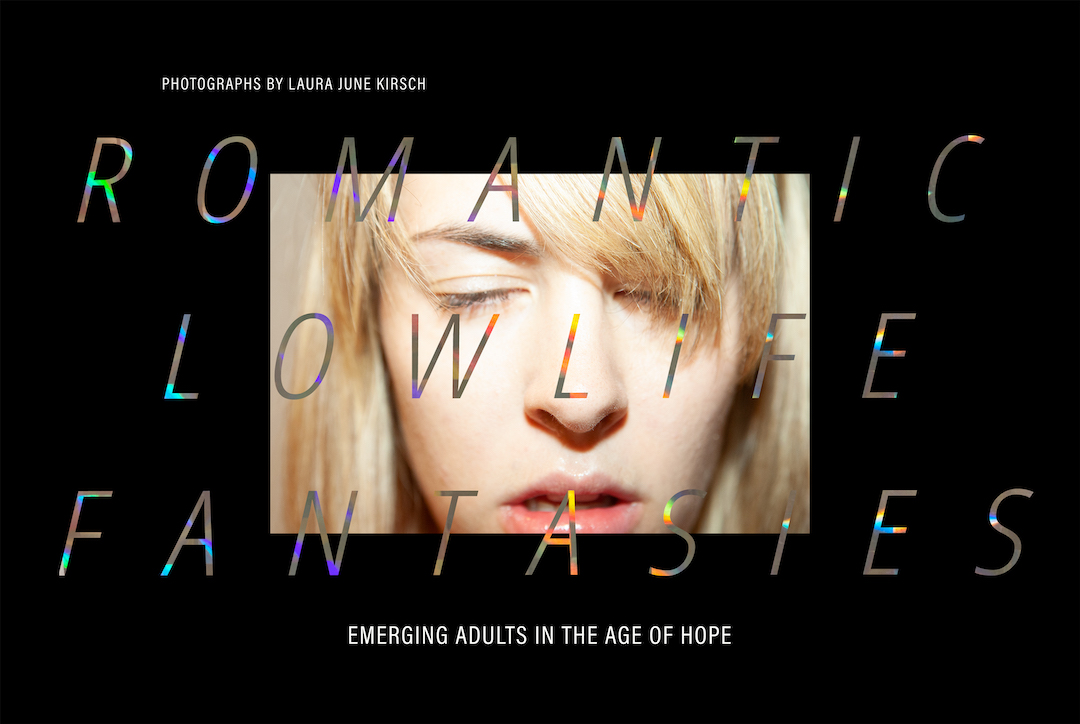

Laura June Kirsch might very well have been one of the photographers covering that celebration—then working until 4 a.m. to get a gallery of party photos online for The Village Voice. This one night pumped the air in the tires for the era that she ended up documenting in her book of photographs, Romantic Lowlife Fantasies: Emerging Adults in the Age of Hope.

The book is punctuated by a series of essays (and one poem) by women, many of whom Laura knew from that era, as she told Whalebone, “who took non-traditional career paths and had interesting stories from this time.”

Their words help give shape to the tales of those nights Laura is telling. Some of the images are party pictures and others are just ebullient flotsam drifting through the age of hope, but, despite being photos of other people, there is a personal declaration from Laura in the collected photos. “A lot of this book is about myself,” she says, “and my own adventure into being a photographer and taking a hard career path in a male-dominated field.”

We had the opportunity to chat with Laura June Kirsch about the book, its inspiration, and attention in the age of technology but there is not one mention of James Fucking Harden.

How did the book come about and how did you land on the angle?

LJK: I’ve always wanted to put out a photo book. I’m a big editor, so I kind of just shot all this content. And then in 2016, I’m like, all right, I need to sit down and start editing it.

I went through all my work and started pulling the photos. It took six months of full-time work to go through everything I’ve ever shot over the course of 10 years, started pulling the stuff I liked. I started thinking about these people—who are they? What does this mean? What does this mean to me? That’s how the concept of the book was incepted. A lot of people think of an idea and then shoot it, but I kind of just let the work happen and then process what it meant.

And so what is the time period that they were shot over? It starts 2008 or so?

LJK: Yeah, it’s the Obama era. I graduated from college in 2007. And then the economy tanked. And I couldn’t get hired for any job I applied for. I went on so many interviews, ones that I was overqualified for, ones that I was perfectly qualified for, and it just didn’t work out. And the photo stuff kept happening, thank God.

I went to school for photo, but I didn’t plan on … I’m kind of an anxious person and freelancing, it’s intense. It’s very anxiety provoking and a hard career path. When you’re worried about paying your bills and the work’s not coming in and you’re hustling, it’s hard. A lot of the time it felt like nagging people just to work to support yourself. I was lucky to be shooting for The Village Voice, but editorial rates aren’t huge budgets so I was having to shoot constantly to make ends meet. It was exhausting. I was having to crank out shoots all the time just to get by. While it was fun, it was also really hard.

At the time, large galleries of people at parties were popular and The Village Voice wanted that coverage. And the funny thing about me, too, is I’ve never loved staying out super late. I love music and I love going out but if it were up to me I would be in bed by midnight. I’d be working until 4:00 a.m. all the time because they’d want those photos immediately and have to edit after the events. It was a crazy time, and so much of it wasn’t very natural for my personality or my preferred choice of living in a lot of ways. But it was fun and I went with it.

The stuff you’re shooting at that time, have you ever really shot anything specifically for the book? Or the book came about from editing this body of photos that you had?

LJK: I always would take photos for myself. A lot of these shoots I just did on my own. I would bring my camera out all the time.

I just knew I wanted to do a book. I knew I had all this work from this time. I knew that this time was special because a lot of these venues closed and things have changed. And this was the last time before everyone was on social media plugged in 24/7. This was kind of the last era before phones took over everyone’s brains. So, yeah, I just, I knew it was an interesting moment in time.

This was kind of the last era before phones took over everyone’s brains.

I graduated from college and volunteered at an Obama fundraiser. It felt like, “Oh, our generation’s making things change for the better, this is great.” And we felt that it was a very positive time to enter your twenties and leave school. And then they got really bad as soon as Obama’s term ended, that really made me look back at this time. I was like, wow. The energy shifted radically once he left and you know who came into play. It changed, but it was really shocking when that happened. When 45 got elected, it was shocking to me. I realized how much I was in this bubble that I was photographing.

That explains the second part of the title of the book. Where did the first half of title come from?

LJK: Well, first of all, it is a Beastie Boys Book reference in an essay by Luc Sante. In the Beastie Boys book the first few chapters are talking about people living in New York City who are creative, who go to shows all the time. I’m like, “wow, this is just like me when I was young.” There was a paragraph about the neighbors in your apartment building not caring about your romantic lowlife fantasies, it was funny and that makes me think of these people in this book. My dreams weren’t glossy—I was doing what I wanted to do shooting all this indie music at small venues. I didn’t think I’d get to be a photographer for work. And it was challenging but great, because I was still shooting music and I had wanted to work in music for so long, so there was that tie-in. You were kind of living out your fantasy life, but it was gritty.

There is kind of a throwback feel to the photography, beyond throwing it back to the Obama-era, similar to those old Beastie Boys photos and rawness and grit of post-punk and that zine-era. More like the Clinton-era. Which runs counter to a lot of the quote-unquote millennial aesthetic. How did you gravitate to that style?

LJK: I grew up in the Long Island hardcore punk scene. That, and I love the Beastie Boys and I grew up with them. They were my first concert in 1998 when I was 13—my sister took me. I grew up going to shows. I started going to hardcore shows and stuff when I was in middle school. So I grew up in that DIY kind of raw scene. It’s just where I come from and how I saw the world.

The photos in the book as a body of work are of a specific time and mostly place, mostly in New York. But how do you think that they connect past that, in more universal ways, outside of that time and place that people might relate?

LJK: I think for me, a big reason why a lot of these photos worked, is people were less self aware then. Anytime you pick up a camera now, people are more inclined to give you a shtick. Back then they were just kind of whatever about it or not as aware. People were more authentically being themselves and they weren’t aware of being documented.

It was less contrived maybe—they weren’t ready for it.

LJK: Now when anybody sees a camera, they have a pose, they have a pitch. It’s just harder. People are selling themselves more than just being themselves. Life is so documented now, their relationship with it is just completely different than when there’s only one person in the room with a camera. During the start of this book people didn’t really have camera phones yet. It was a novelty for someone to come in with a fancy SLR, it wasn’t that common. People still had little point and shoots, but to have someone come in with a nice digital camera at the start of this was like, “oh, let me see that camera.” That was usually what happened. “Let me see that camera, let me take a photo of you.” There’s just all these funny pictures of me, blurry pictures, my head’s cropped off from random people trying to use a professional camera. It’s really funny and always gave me reassurance why I was needed.

That was usually what happened. “Let me see that camera, let me take a photo of you.”

There’s one photo in the book of people with those yellow glasses—must be 3d glasses right? It’s totally evocative of those very classic 1950s photos where everybody’s sitting at the cinema looking in the same direction with 3D glasses on but a modern version. What are they looking at?

LJK: That is one of the later photos and I just had to put it in because it was so good.

Yeah, so good.

LJK: Flying Lotus debuted this 3D show, he’s a multimedia artist and he’s amazing. He made all these crazy graphics for this insane show and it was next level. It was really impressive. And yeah, and he got all those people to be completely engaged in his art. At a festival. And that is so hard to do. And that’s why that picture was just too powerful. I’m like, “all right, I have to throw that in, even though it’s from a year later than the other photos.”

And it’s just like this nod to the future of tech and where everything’s going to with NFTs and where things are moving. The things that are capturing people’s attention now to get them in the moment are just—it has to be something totally different.