Ayana and I became fast friends when introduced to one another by Dune Ives, the Executive Director of the organization I work with: The Lonely Whale Foundation. Born and raised in Brooklyn with a PhD in Marine Biology from Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Ayana contributes to some of the most impactful publications of our era: The New York Times, National Geographic, and The Guardian to name a few. She’s recently moved back to New York City, and is actively working on various ocean conservation efforts within our big apple.

In gearing up for Lonely Whale’s Urban Ocean Love Story this next Monday at Soho House—which will highlight efforts being taken to preserve and rebuild NYC’s waterways—I caught up with Ayana to discuss her international efforts in ocean conservation as a marine biologist + policy expert, as well as get the conversation flowing on what we can do to help ensure that our own favorite bodies of water remain safe and beautiful.

This is part two of four in the Lonely Whale Interview Series, brought to you by our sustainable seafood friends over at Norman’s Cay NYC.

Where are you from?

Fort Greene, Brooklyn.

And where do you currently call home?

Fort Greene, Brooklyn! I left the neighborhood for college, and after 18 years living amongst Cambridge, San Diego, various Caribbean islands, and DC, this autumn I moved into an apartment a block from the brownstone where I grew up.

Do you remember your first time falling in love with the water?

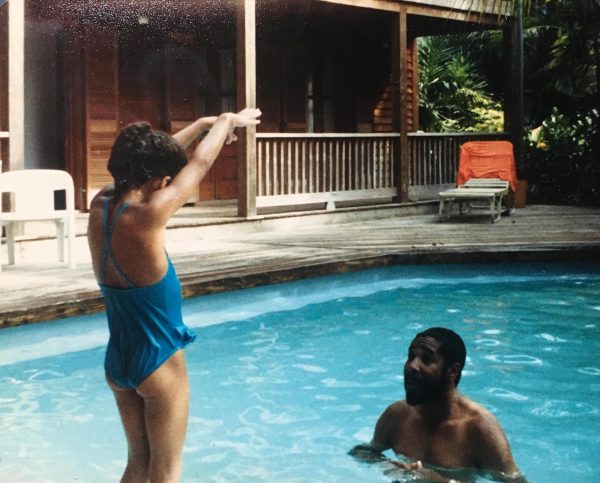

I was five years old and in Key West, Florida on a family vacation. My parents brought me there specifically to teach me how to swim. I spent endless hours in the pool of our bed and breakfast. I would eat lunch standing in the shallow end—I never wanted to get out.

A young Ayana in Key West. Photo courtesy of Ayana E. Johnson

We had the pool to ourselves because the other guests refused to go in after my dark-skinned Jamaican father was in there playing with me. I didn’t understand racism at the time, but I loved being able to do cannonballs with impunity.

Also on that trip, we went to an aquarium and I got to hold sea urchins and starfish and feel their tube feet crawling across my hands. From a glass-bottomed boat, I saw my first coral reef. I was fascinated by the colorful fish coming up to the surface to eat the snacks we were throwing over the stern (note: this is not cool—it was the 1980s; do not do this now).

By the time my mother noticed I was armpit deep in a bag of cheese popcorn, blissfully unaware that I was covered with hives due to my dairy allergy, I had decided to become a marine biologist.

Can you give us your favorite sea creature?

Octopus. Hands down. Super intelligent and they have three hearts. Plus, see below.

Most memorable water-related movie you’ve ever watched?

Not a movie per say, but these YouTube videos of a mimic octopus. They are incredible. And I’m excited about how burgeoning virtual reality technology will enable so many more people to experience life beneath the surface of the ocean.

Favorite beach you’ve had the pleasure of visiting?

Oooh, this is a very difficult question. Two Foot Bay in Barbuda is one of the most beautiful places on the planet.

Ayana at Two Foot Bay. Photo courtesy of Daryn Deluco

I also have a soft spot for Windansea Beach in La Jolla, CA where I lived for five years.

East Coast or West Coast, and why?

The East Coast has my heart, but a dose of Big Sur every now and then certainly doesn’t hurt.

Was there a specific moment or interaction that originally attracted you to your cause?

In college, I studied abroad in Turks and Caicos at the School for Field Studies. That was my first real academic experience with marine biology. Learning about the diversity of species (and all their Latin names) and the complexities of coral reef ecology was fascinating. But what sucked me in was studying economics and policy simultaneously. Realizing that conservation work can, and in fact must, be multi-disciplinary convinced me I could be happy making a career out of it.

What has been your greatest inspiration in staying dedicated to your cause?

The economies and cultures of coastal communities. Ocean conservation is not about fish. Fish are swimming around trying to eat, make babies, avoid getting eaten; they are doing their jobs just fine. Ocean conservation is about people.

Ayana interviewing fishers in Curaçao. Photo courtesy of Ayana E. Johnson

I have interviewed around 500 fishermen and SCUBA divers, and the most poignant anecdote was from a 15-year-old fisherman who summed up the dramatic depletion of the ocean by saying: “Previous generations used to show the size of fish they caught vertically. Now we show fish size horizontally.” In other words, a big fish used to be as long as a fisherman was tall, and now a big fish is only as long as your shoulders are wide. The highly-valued groupers, snappers, cod, and other large predatory fish are effectively gone in many places, which hurts livelihoods and destabilizes ecosystems.

Ocean conservation is a matter of cultural preservation. The people most hurt by overfishing, climate change, and pollution are poor communities and communities of color. I keep doing this work because I ocean conservation is a social justice issue.

What is your biggest fear for the future for our oceans?

That we’ll give up fighting for a healthier ocean. The ocean is resilient and we have so much evidence that the ocean (and nature in general) can recover if we just give it a break. But the immediate pressures on natural resources push us into short-term thinking – whether that’s the result poor fishermen trying to keep food on their tables or of corporate greed that results in destructive coastal construction. Meanwhile, ocean conservation is the long game. So we need to continually remind people that addressing humanity’s grand challenges, from food security to climate change, requires a healthy ocean.

One thing you believe everyone can + should be doing to help preserve our natural bodies of water?

Choose sustainable seafood. Support local fishermen who are exemplary environmental stewards. Ask lots of questions at restaurants and markets to show that consumers care. Cut single-use plastic out of your life – so much of it ends up in the ocean. Choose eco-friendly (and ocean-friendly!) resorts when you travel. Reduce your carbon footprint. Shout your support for setting aside (as scientifically-recommended) 30% of our ocean as protected.

More broadly, we need millions of local and community efforts, billions of individual actions, and to build the political will for major national and international shifts in fishing, coastal development, and climate policy.

Keep up with Ayana and her love for the ocean via her website. Thanks Ayana!