At Least They’re Enjoying the Ride

Call it stoke that will steal your face. The action sports scene has reached astonishing peaks in the last decade, due in large part to the larger-than-life athletes achieving larger-than-life feats on camera.

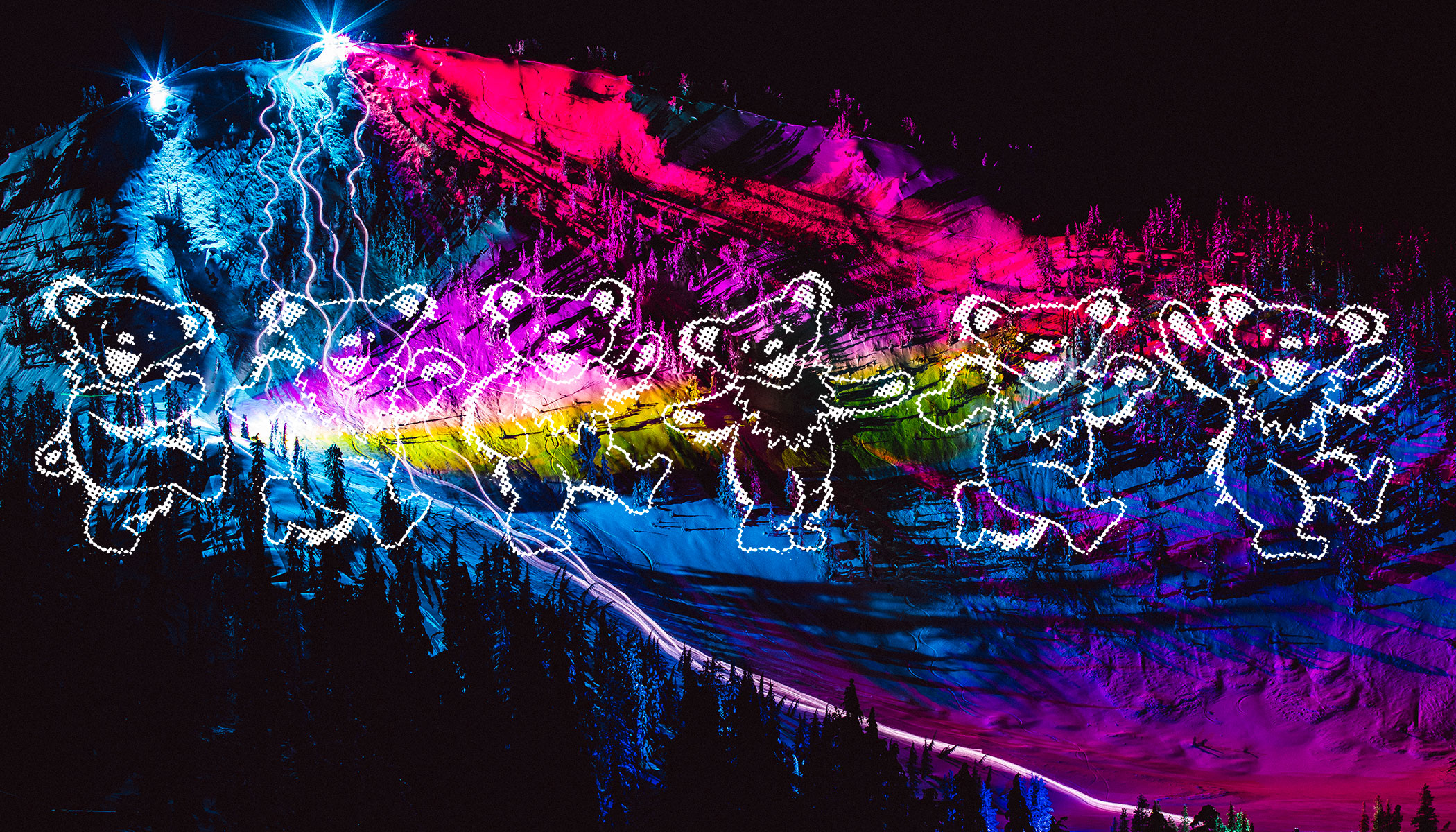

Our friends over at Teton Gravity Research, with Director/Producer/Artist/Athlete/ Badass-Dad Chris Benchetler, have gone even further to give us a film of unparalleled visuals and some familiar tunes in his latest, “Fire on the Mountain.” As an avid fan of the Grateful Dead, Chris merged his passion for snow and surf, art, and the Dead in a film of eclectic style and some super hypnotic cinematography.Bringing along some of his fellow athletes (and fellow Deadheads), Chris worked with Rob Machado, Kimmy Fasani, Danny Davis, Jeremy Jones, and Michelle Parker to bring together one trippy ride. Just as the Dead did not fit their music into an established category and had a tendency to meander, this short film finds Chris, Rob and a cast of some of the world’s best athletes on an improvisational journey. Shot during a snow and surf road trip, the journey starts in California, the birthplace of the Grateful Dead. The film finds them all in a psychedelic dreamscape as they appear as skeletons shredding snow under the moonlight at Mammoth Mountain—and then on the water in Indonesia. Similar to a Grateful Dead show, everyone starts and ends in the same place but each of their respective experiences is a journey of its own.

Watch the trailer

When did you begin listening to the Grateful Dead and how did it first go down?

ROB MACHADO: I honestly can’t remember the first time I heard the Dead. My musical journey started at such a young age and quickly exploded in so many directions with Hendrix, Zeppelin, Marley, Dylan, the Dead. And then into the alternative world with Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Jane’s Addiction, Smashing Pumpkins, Chili Peppers, Sublime… and then came our discovery of punk rock with my good friend Taylor Steele… Minor Threat, Bad Religion, Pennywise. The Dead was always in the rotation and never left.

CHRIS BENCHETLER: Luckily my dad was always into classic rock, so my music library growing up was full of The Stones, Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, the Dead…I can’t say I ever identified with one over the other, I just loved that entire genre and would explore more and more of the music. Fast forward into my early 20s when a good friend, Konrad Leh, who is the quintessential Deadhead, started staying and skiing with us more and more in the winters. He’s been to hundreds of shows pre-’95, and hundreds after. It was all he listened to any time you were in the car with him, then I picked up guitar myself—very poorly—but started to hear the magic. Then it really solidified and became a staple when I went to a Dead & Co show a few years back and saw the improvisational magic in person.

What drew you to pairing the Dead and surfing and snowboarding for this film?

CB: Honestly, music is one of the most important ingredients of filmmaking, and the Dead’s improvisational tapestry lends itself extremely well to riding mountains and waves. No one line or wave is ever the same, the same way that no Dead song is ever played the same. Pair that with meeting Brian Francis who solidified a Dead collaboration with Atomic Skis and myself, then that led to Dakine and TGR getting involved. Then add a film concept for a night shoot at Mammoth Mountain that I’ve been marinating on for years after a film I did with Sweetgrass a while back. Plus Rob and I had been talking of ideas to blend our two sports into a film, so I just tried to blend and marry all those ideas and concepts and really play off the collaboration element of inspiration, art, sport, people, and music into one cohesive visual art piece.

Improvisation is the silver thread that weaves this film together. Skiing, snowboarding, surfing, and art is about improvisation and harmony with nature.

How many Dead shows have you been to?

RM: Never had the chance.

CB: I’ve unfortunately only ever been to Dead & Co. and a Bob [Weir] and Wolf Bros show at the Ace. I was too young when Jerry passed to ever see the real deal, but I’m very thankful for all the iterations of the original band.

Why do you think the Dead still holds cultural relevance today, 50+ years after they started?

RM: It’s crazy how big of a following the Dead has. Since we’ve started working on this project and I’ve reconnected with the music, I feel like my awareness of Deadheads has risen. They’re everywhere! It’s amazing to think that the band has covered so many generations and are still making music. Good music stands the test of time.

CB: I think the connection in the Dead community is the band’s authenticity. They never conformed to radio or even the studio, and always gave the people a show to remember for a lifetime. I think they’ve shaped and inspired so many people’s life trajectory, that the loyal following will live on forever. Especially with them still making such incredible music. That era and their jams will stand the test of time.

As an athlete and an artist, what’s it like diving into such an involved project like this and with a band you’ve admired for so long?

RM: This has been Chris’ brainchild from the get-go. My first taste of what was really going on was when I showed up in Mammoth for the night shoots and I saw the mountain for the first time. I was completely blown away. The mountain. The lights. The action. It was off the charts. Watching these guys do what they do best in that environment is something I will never forget. So grateful to be a part of it.

CB: To be honest it’s been an extremely wild ride. I’ve put so many hours of my life, and so much energy into this project, it’s a bit unhealthy. Luckily I have a team of people that all share that vision, and I trust deeply. From the co-director and lead cinematographer Tyler Hamlet to Executive Producer Brian Francis, the editors, each athlete, the artists I collaborated with, the lighting crew, the photographers, everyone. Working alongside Rhino Records, Warner, Dave Lemieux, Bill Walton, etc… has been a surreal experience. I’d never thought I’d have a direct line of communication with such an iconic entity. They are all very passionate and extremely supportive of the vision. I’m very grateful I pitched this whole idea, even with the years taken off my life to make it happen.

How did you approach the filmmaking process with the Dead in mind? Basically what aesthetics did you carry over from the music to the film?

RM: From my perspective, it was all about the athletes that Chris chose for the film. The styles of riding were what made the music and riding connect. Everyone was in the zone and all about it. Freeriding and finding lines in the dark made for something really special. The freedom to express yourself in a whole new environment was so challenging and so rewarding.

CB: It was very much about collaboration and improvisation with nature. As I said before I handpicked each athlete that inspires me most, like Rob, and created a vision that would highlight each of them in their element. Each of them shares a passion for music, and read the mountains and waves in a way that directly reflects how they approach life. Then throw in the Dead and how they approach a show, it all blends extremely well with the concept for the film.

What were some of the unique challenges of this film and how did it affect the way you skied and surfed?

RM: On the mountain, watching those guys and gals rip through the trees in the dark and fly over huge gaps completely gave me a whole new appreciation for what they are capable of. Next level shit.

The ocean was a whole different ball game. The first night we thought it would be pretty easy… we were so wrong. I paddled into the lineup… or where I thought the lineup was, and I was immediately cleaned up. It’s a whole different feeling of being cleaned up in the dark. You know the reef is there, but how close is it? How far did I just get pushed in? I had to learn how to really trust my other senses and my instincts. A lot.

The next night I put a buoy in the channel just to have something to always go back to and to help me line up. But I was still staring in the dark trying to make out anything that might look like a wave. Sometimes I would paddle for what I thought was a wave and there wouldn’t be anything there. Other times I would start turning around to paddle for a wave and out of the corner of my eye, I would see the lip falling from the sky and landing right on me. And all of this was just to catch a wave. Once I was on a wave then I had to try to make sense of what kind of wave I was actually on. During the day it was a perfect little left point, but at night it became a whole new beast. I caught waves where I found myself so far on the shoulder that I would do the smallest bottom turn and I would kick out. Other times I found myself bottom turning into a right coming straight at me and blasting me straight onto the reef.

The lights on the board and the suit made it almost impossible to see anything. But I didn’t give up and I put in some serious hours to get a few decent rides. It was the most challenging thing I have ever done in the ocean by a mile. After the first four-hour session I got back to the boat and was physically and mentally drained. I was a noodle. It was sensory overload on steroids. Everything in my body was working overtime just to make a wave.

The way we draw lines down a mountain, wave, or canvas is similar to the way the Grateful Dead approached their music. You never know if you are in for the best turn or barrel of your life.

CB: There are so many elements of this project that brought a level of challenges I’ve never experienced. The most obvious would be the actual performing under the lights. Dealing with 130-mph winds, snow conditions, avalanche assessment, freezing fog, and being able to actually see, and then needing to put it all together from tricks to turns, etc. From an athlete perspective all those elements add complications. Then take the trip to Indo with Rob, and that was a whole new can of worms in a completely new and uncharted territory. Surfing is a massive passion of mine that is single-handedly the most complex sport to learn. I still eat it on drop-ins, turns, etc, etc… But then actual paddling out with Rob, seeing the complications for someone like him that has completely mastered the sport in my eyes, and then trying to catch a wave myself was nearly impossible. I’m so grateful I actually tried to surf so I could truly understand how skilled Rob is. You legitimately couldn’t see anything. There is no reflective light or object other than the white water for the lights to catch, so seeing a transition of the wave, or when a wave was going to break was impossible. I was blown away at what he was able to do in such challenging elements.

Then if you ask me that question as a producer and director, that’s where I lost multiple years off of my life. It’s one thing to have an idea, but to actually execute in a way that makes you happy is so extremely challenging. So many stars need to align, and so many helping hands, and people in place to bring a dream to life. Seeing Sweetgrass set the lights up, deal with freezing generators, the wind ripping gels off and knocking over stands… Me trying to create a skeleton light suit with no electrical knowledge, then the amount of frozen wires and soldering in the field. The travel to get 30 bags of gear to a remote island in Indo. Aligning everyone’s schedules with weather windows. Getting people to see and believe in your vision and support the project. There’s seriously a list of 100 challenges floating in my head, but in the end, it was all extremely worth it and I’d do it all over again.