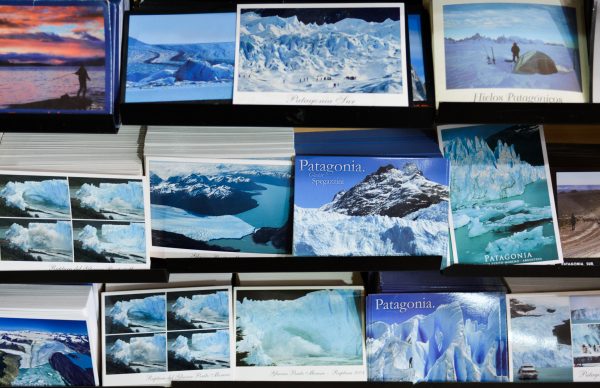

Avery Schuyler Nunn takes a Nikon and a Notebook to South America

El Calafate, Argentina, is known as “the gateway town” to Los Glaciares National Park, home to glorious Patagonian glaciers. After taking three flights down from Philadelphia, I arrived in El Calafate to begin my backpacking trip through the region of Patagonia, shared by Argentina and Chile.

These Patagonian glaciers have been forming for millions of years (scientists estimate that this formation began during the last Ice Age, which started approximately 2.6 million years ago and ended around 11,700 years ago), and are of both historical and cultural importance to the nearby town of El Calafate. I walked its streets wondering how glacial melting would affect the town, as every business heavily relies on the glaciers to bring in travelers.

The main attraction.

Through compression melting, glaciers erode the land beneath them, shaping the landscape and creating the views that Patagonia is famous for. In turn, glacial till provides fertile soil for growing crops, and deposits of sand and gravel, that is used to create concrete and asphalt to build structures and homes in El Calafate. But as ice sheets melt at a faster rate, the loss of glacial ice reduces the amount of freshwater available for plants and animals on land, greatly affecting the ecosystems.

My first experience seeing a glacier was while hiking upon the stratovolcano Cotopaxi, in Latacunga, Ecuador, during a geological field study in college. While looking out across the paramo between note-taking, I listened to my professor speak of how the vast landscape would one day morph to a topography similar to that of Kansas. Flat, dry, lifeless. I felt my concerns quickly grow in fear for the future of such a place and its surrounding ecosystems due to climate change. Glaciers store about 69% of the world’s fresh water, and if all glaciers melted, sea level would rise approximately 70 meters (230 feet) worldwide. So, post-grad I returned to the glaciers in South America, to see them while I can and learn from them more closely. With my crampons on, notebook in hand, and a flask filled with pisco sour and glacial ice, I was ready to explore the frozen world.

As greenhouse gases trap more energy from the sun, the oceans absorb more heat, resulting in an increase in sea surface temperatures and rising sea levels. Many people recognize that the climate has changed naturally many times before, shifting between glacial and interglacial periods, and don’t believe that this time is any different. But as my climatology notes have reminded me: while it is true that the Earth is far older than 800,000 years and that it has experienced climate change throughout its multi-billion-year life, CO2 is currently entering the atmosphere at a rate faster than during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, which is one of the most dramatic warmings to have happened in Earth’s history.

Many use the fact that there have been record snowfalls and polar vortexes in recent years as evidence against climate change, but climate change is far more complex than a simple warming of the planet. In fact, scientists see these extreme winter weather conditions as even more evidence that climate change is happening.

Polar ice melt is one of the main causes of sea-level rise, which brings a reinforcement of climate change and loss of biodiversity. But how can we truly help that? By taking little steps to reduce your carbon footprint, alleviate climate change, and slow ice cap melting. Simple things you’ve heard before such as reduce, reuse, and recycle, walk more, eat green, and use less energy, but informing and inspiring others to reduce their carbon footprint in addition to your own is what will ultimately help the planet on a grander scheme. In turn we can aid this beautiful place that deserves our protection, for future generations to learn from, explore, and admire as much as I do.

…And maybe pop over to see some glaciers to see what we are in danger of losing. Moments of admiring the wildflowers included.