Cross-processing, Hasselblads and Hip-Hop

Danny Clinch has been carrying a camera around since he was seven years old and he found Keystone point-and-shoot at a neighbors garage sale. You could say that was that start of his fascination with photography and the beginnings of what is now a camera collection that numbers in the hundreds spilling from gear closets. Danny has put the collection to good use shooting the likes of Bob Dylan, Nas, Bruce Springsteen (shooting seven of the Boss’s album covers and filming “Devils and Dust”), Tom Waits, Fleetwood Mac, Metallica, Johnny Cash, Jay Z and many other people you have sang along to on the radio. He’s also a judge in the Whalebone Photo Contest and will lend his eye to help us pick the photographers who will be celebrated as finalists.

Danny was kind enough to share with us a little bit about what he’s learned along the way, which lucky for you and us, one of those things is showing grace, kindness and humility and giving something back.

Danny Clinch talks about finding your style, not following trends, the document and waiting for the right moment.

Photo Danny Clinch. Neil Young.

What are the elements in your personal view that make for a really memorable photo?

Danny: Lighting, composition and a moment, to me. That’s when it all comes together. The moment being the most important, in my opinion. I would sacrifice the others to catch a great moment.

To me, it’s when people let their guard down, when people reveal themselves. Those things are super important to me as a portrait photographer, someone who photographs people.

One thing you know now that you wish you had known when you were starting out shooting?

Danny: Back then you’re shooting film and having to make a choice. Am I going to shoot Tri-X black and white film or am I going to shoot color and why? I started my career doing a lot of black and white photography. I liked to be right in the middle of it, so I was shooting with a wider lens. I was getting right in it and I was a big fan of documentary photography and a lot of that was shot in black and white. A lot of my heroes used black and white photography.

As I went on in my career in my first portfolios I was showing around were pretty much black and white. A portfolio of black and white photography. There were people that were telling me like, “Well, my advice to you is to shoot some color. You’re never going to get anywhere shooting just black and white photography.” I was like, “Well, if someone’s got an assignment for me in color, I’ll put some color film in my camera.” I think the point of that story, for me, was it didn’t get in the way. I just stuck with what I felt was a natural fit for me and it’s like, “This is my voice right here at this moment and this is what I have to say.” In the end, I stuck to what I loved and what I felt really passionate about and the work still came.

I personally feel the truthful, honest photograph is where it’s at for me.

What was the process of finding that voice like?

Danny: Back in the ’90s I was shooting slide film and processing it in C-41. That’s called cross-processing. People used it a lot in the ’90s in the music industry shooting musicians in hip-hop and indie rock and all that stuff. Then it was cool. It was a look and it was there, but I look back on it not as fondly as I looked at it when I was doing it. I always look back at those images and think, “Oh, man. Could I print those and make them like just a classic color photograph?”

I just tend to be careful about trends. When I looked back at that later, I thought to myself, “I personally feel the truthful, honest photograph is where it’s at for me.” Something that has an authentic sort of approach to it. A classic. You look at a black and white photograph and it’s simple. It could be a simple portrait or a great captured moment and it just feels classic. It has this feel to it that I don’t believe will ever go out of style. You look back to the ’90s hip-hop and all the cross-processing and you look at it, it’s trendy and, in fact, it has gone out of style. But you look back at Robert Frank photograph or an Irving Penn portrait or Avedon and they don’t go out of style.

I mean, sure the styles may be different but the photography style and composition—that doesn’t go out of style. It resonates to this day and you don’t look at it with your head tilted sideways like, “Why did they do that?” Today, I see a lot of that. I don’t know what everybody uses, but there’s something that’s called clarity. If you nudge the clarity a little bit, I think it overall can help an image that you’re posting on the web. It gives it some contrast. It brings the highlights in, the shadows, but people just … They just whack that clarity thing over and just it looks like a cartoon. I know I’m exaggerating when I say that, but I’m not. Some people really go for it and I find that people who are relying on that as their tool of photography, I’m not for it. Again, could be someone breaking the rules and creating really beautiful work. I think that it just doesn’t feel right to me.

Photo Danny Clinch. Tom Waits.

Was there a project or even an era where you felt like it clicked and you got it?

Danny: I had a moment when I was younger when I was in photography school and I took a portrait of my two nephews holding my niece who was an infant. My mom was holding her hand in and holding up the kid from outside the frame so that they didn’t drop her. The photograph, to me, really resonated with me and I thought, “Maybe I’m on to something. I feel like I’m really … The composition is nice. The moment’s great. There’s a little surprise in there.” All the elements I think that make a successful image.

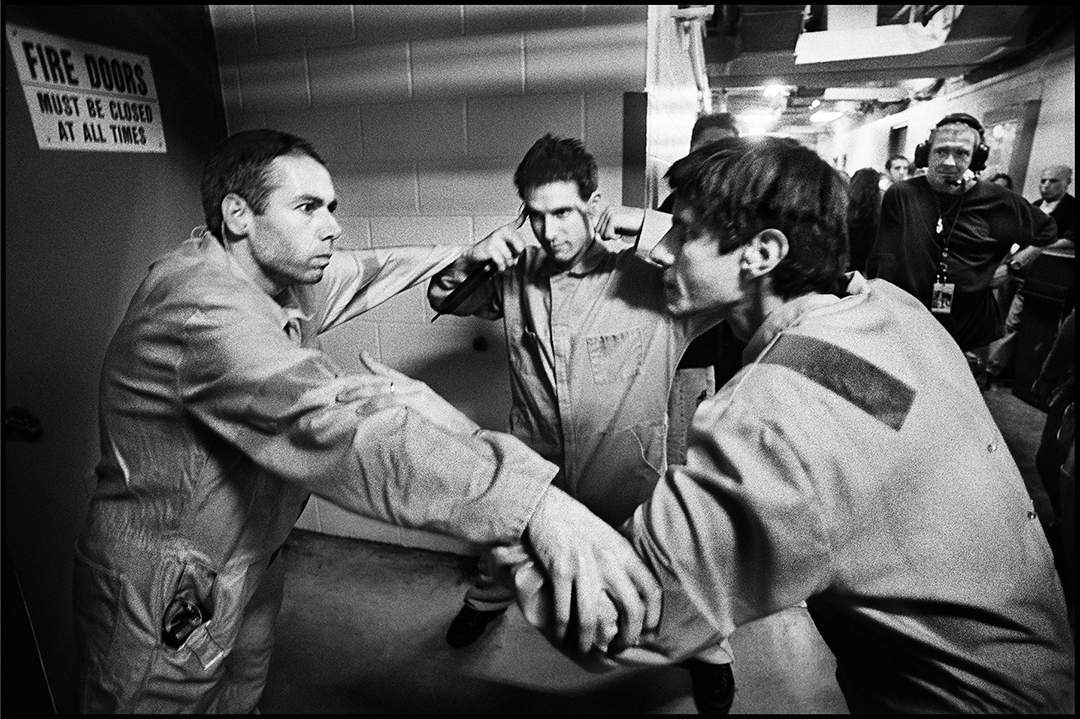

You have to get a place where you feel like, at least for me personally, where I felt like I had come through on an assignment and felt like I really got it and felt like from that moment forward that I was on my way. That, for me, was a shoot I did for Spin Magazine with the hip-hop group 3rd Bass. I got an assignment. It was my first big assignment, and I felt like I was in the big leagues. But I was like, “Okay, I’ll be in the big leagues if I pull this off and this photograph resonates with me. Then when they put it in the magazine it looks like it belongs there.” That was the moment for me where I was like, “Okay, I understand this. I get this. I know how to shoot for a magazine. I know how to shoot for composition and to take some chances and all that stuff.”

Photo Danny Clinch.

What’s something that you would tell everybody who’s shooting that they could do that would improve their photography?

Danny: Like anything, I think that you have to have your own point of view. It has to be evident in photographs. Like, what’s your point of view? What is your style?

It was always such a struggle and so stressful. You’re at school. You’re trying to figure out your style and you’re trying to force a style. You’re copying everyone else’s style or … How do you do it? What I’ve realized for me was that what … At a certain point, I asked, “Well, what’s my style?” I realized I like to shoot black and white photography. I liked using a 28-millimeter lens, a wider lens. I liked being in the middle of things. I liked music. I liked cars and motorcycles. I liked being able to stick and move and be on my toes and all that. When you put all those together they become who you are. Right?

That becomes your style. Do you like tabletop photography? Are you a person whose attention to detail and lighting and you can sit there for hours and move things around on the table until they’re just perfect and the lighting’s just perfect and all that sort of stuff? Then make your style what you love. The thing that I recall is people saying, “Don’t put a tabletop image in your portfolio if you hate shooting tabletop because what’s going to happen is you’re going to get hired to do that and you’re going to be like, ‘I don’t want to do this.’” I mean, sure, when you’re younger you’ll do whatever you can to make a buck and that’s one thing, but what I’m talking about for your art purposes, for your life’s work for what you want to be known for you don’t want to put that in your portfolio.

Those kinds of things. Do you like fashion? Whatever it is that you’re excited about. What type of camera do you like to shoot? Really if you logically think about it, all of a sudden you’ll be like, “Oh, shit. That’s a good point. I like shooting with a Hasselblad. I like the square format. I like film. I like fashion. I like shooting on location and I’m going to put that in my portfolio.” When you show it around people are going to be like, “Hey, we need someone who shoots Hasselblad natural light on-location fashion. Hey, there’s Joe Smith. Let’s grab him.”

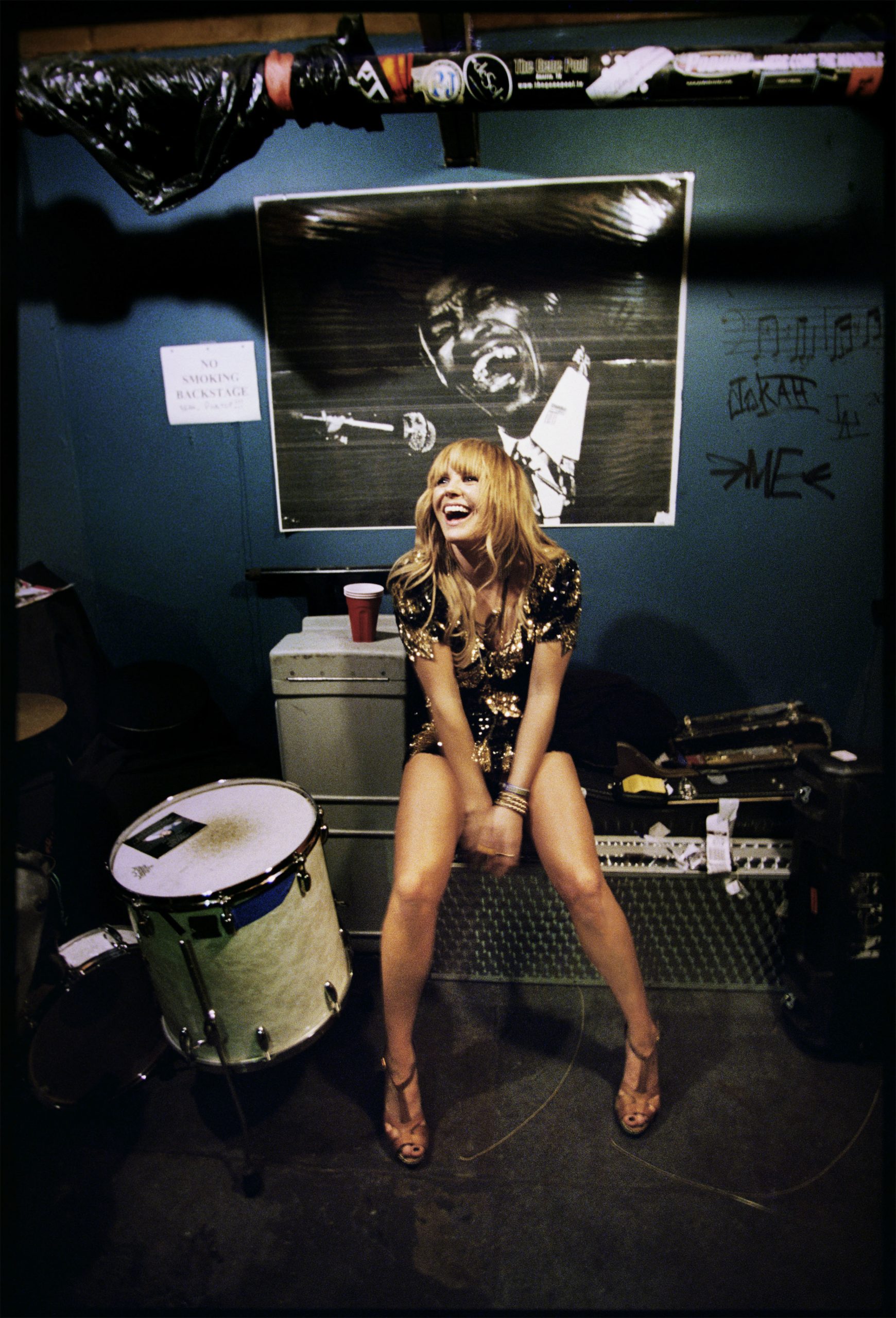

Photo Danny Clinch. Grace Potter backstage.

Did your music fandom develop in parallel with your appreciation and feel at photography or did music come sooner or later?

Danny: I mean, my photography came early in my life, but so did music. They kind of grew together and I feel like I honestly had sort of a very specific limited upbringing in regard to music. It was like it was AM/FM radio. It was my dad’s 8-track cassette of ‘50s greatest hits. The Big Bopper, Elvis, Carl Perkins, Ritchie Valens, Buddy Holly, all that. Then my buddy’s older brother and sister who were into Jackson Brown, Cat Stevens, Warren Zevon, a lot of classic rock stuff. Springsteen, Bob Seger, bands like that, that I started to … that I grew up listening to. I didn’t really have an older cousin or brother or something that was like, “Come on. I’m going to take you to see The Stooges or The Ramones,” or whatever. It’s like all that stuff came later for me, so in a way, they kind of paralleled each other.

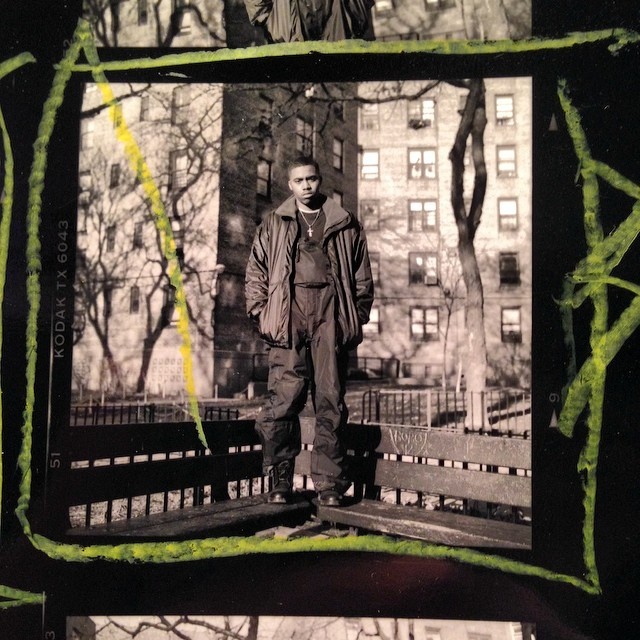

My education in photography and then my education in music, and being thrown into hip-hop when I was a young photographer getting my start. That was my introduction to hip-hop was going out and photographing Nas in Queensbridge.

It’s been cool because I went from shooting hip-hop stuff, and indie rock, and all that to actually one of the things I’m most proud of is that I didn’t get stuck in just shooting hip-hop and that. I’ve then went from hip-hop, Nas, Big L, et cetera into Jane’s Addiction and the Chili Peppers and Smashing Pumpkins into Neil Young and Bruce Springsteen and Pearl Jam and all that. Then there’s Willie Nelson, and Merle Haggard, and Johnny Cash, and it’s like I’ve photographed all these people. It’s kind of mind-blowing really.

Was there a first time when you were like, “Holy shit. I’m in the room with one of my heroes. How did this happen?”

Danny: Yeah, definitely. There was a moment when I was doing well and I was photographing a lot of interesting people, and I had shot Johnny Cash at that point and loved that. I think I had done some Metallica, but when I got to photograph Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan, which happened … I actually got the assignment on the very same day. I got a call from Jeff Rosen, Dylan’s manager in the morning and then I got a call from Bruce’s art director that afternoon. I was like, “Wow.” That stuff was mind-blowing. To be standing there waiting for Bob Dylan to show up to the photoshoot and wondering if he’s actually ever going to show up. Because I had done a lot of artists where they’re like, “Oh, actually they’re not coming.”

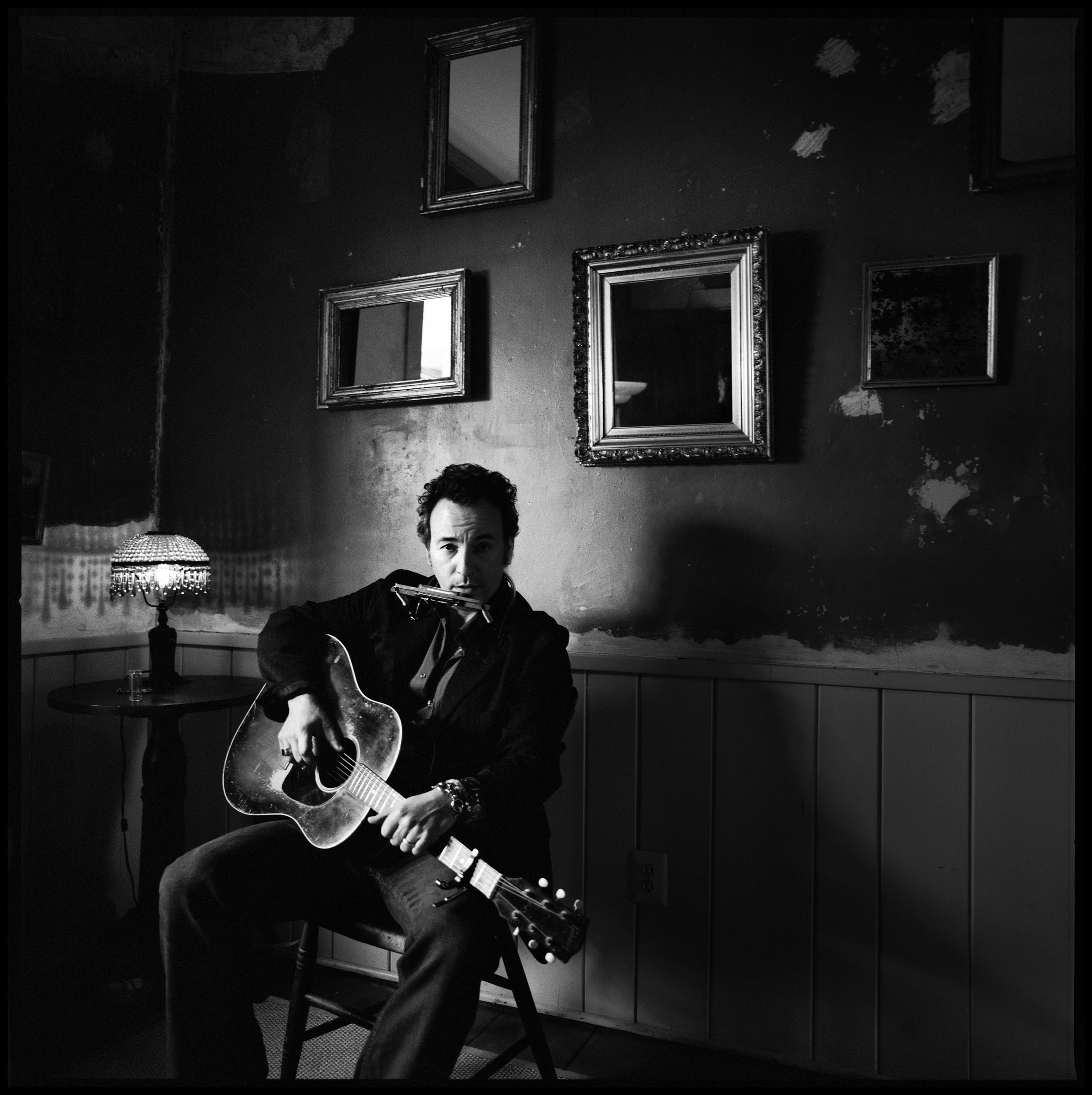

Photo Danny Clinch.

But I got a call from Dylan’s publicist at the time saying, “We’re in the van. We’re on our way. Are you familiar with that Little Walter Greatest Hits album cover? Bob loves that cover. We want to do something like that.” I was like, “Hell, yeah. I play harmonica. Bring him over.”

I was like, “Wow.” That stuff was mind-blowing.

Also, another moment where that happened was with Springsteen. I was shooting the “Devils & Dust” film. I was just in this room and Bruce was playing these songs for us. He had asked me to come and film it, and I had my Hasselblad there and in between I was taking photographs. I looked into my Hasselblad, and I just got to this moment where I looked through the camera and I was like, “Wow. That is Bruce Springsteen on that other end of this camera. Not only am I getting to photograph him, but he’s trusted me to make this little short film.”

I remember asking his manager afterwards. I was like, “How did I end up shooting this?” Because I didn’t want to say this before I shot it. I waited until afterwards. I was like, “How did I end up getting chosen to shoot this thing? I just don’t understand it.” She was like, “Danny, I’ll be honest with you, I asked Bruce the same question beforehand and he said, ‘Well, Danny’s got soul and I’m sure he’s going to do something good with it.’”

Photo Danny Clinch.

What’s the first camera that you bought yourself?

Danny: My first camera I bought at a yard sale when I was about seven years old. It was a Keystone.

Actually, recently somebody was throwing out a bunch of cameras—and this happens to me often where someone will send a box of cameras over to me and be like, “Hey, I’m throwing these out. If you want them feel free. I don’t know what makes sense to you. You can just toss them in the trash.” They were all trash-worthy cameras, but one of them was the Keystone and I was like, “Holy shit. This is the first camera I bought from my neighbor when I was like seven years old.” I just kept it and I was like, “Oh, my God. This is amazing.” Yeah, it was a small, small little 126-format camera.

What’s a photograph, or a few photos, that someone else has taken that has really resonated with you and stuck with you for whatever reason?

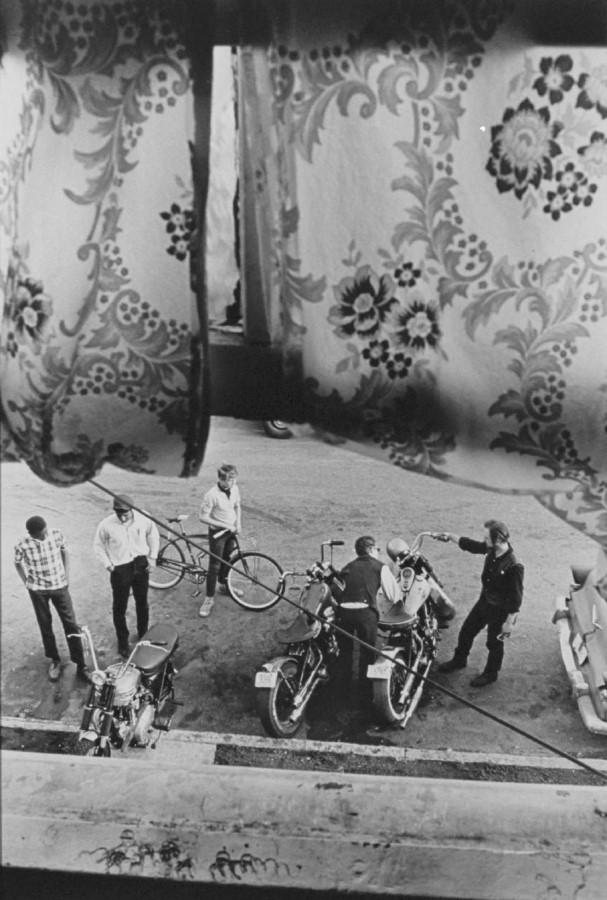

The Danny Lyon photographs really mean a lot to me. He did a series called The Bike Riders and the fact that he was shooting with a lot of the cameras that I loved—loose captured moments. There are several from The Bike Riders that really stand out to me, but there’s one in there that’s always been really beautiful and sort of inspirational to me. It’s like he was inside of the second floor of a house or an apartment or something like that and there were people standing out parked with their motorcycles out on the street, and you can see the curtains. He frames them up within the curtains of the window and it’s just put me in the place where he was. In a way like a voyeuristic photograph or just framed beautifully and a great story being told there. I love that photograph.

Photo Danny Lyon. From The Bike Riders, 1966.

I love a lot of Jim Marshall’s photographs. Dylan rolling the tire. You talk about a moment that I talked about earlier. There’s so much great story in there. Dylan’s like a little kid rolling a tire down the street in New York City. I think about Mary Ellen Mark photographs of the circus. They stand out to me in my mind all the time. There’s a beautiful portrait of a … I guess kind of like an elephant trainer at an Indian circus and he’s got the trunk of the elephant is just wrapped around his head. It’s just such a beautiful document and I worked for Mary Ellen Mark as well back in the day and I always loved her work.

One of the things that was really inspirational to me was the Irving Penn portraits. Like World in a Small Room or just his backdrop portraits everywhere. The North Light portraits and there was … Again, it’s funny how I keep thinking about the motorcycle portraits, but there was … He did portraits of all sorts of people. Shooting for Vogue and photographing artists, and poets, and actors, and the people who were part of the culture of the times. He went to San Francisco once and did Big Brother and the Holding Company. I think he did the Jefferson Airplane, and then he also just did a portrait of a biker family. Maybe a Hell’s Angel with his wife or girlfriend and their little child. That photograph also, to me, was just a great document, a simple portrait with natural light.

Photo Danny Clinch. Nas, from the Illmatic sessions, 1993.

What about of your own photos?

Danny: I think Johnny Cash, that was the cover of “Solitary Man,” means a lot to me. I did the last sort of album session with John Prine. That means a lot to me. Really, I think the Nas session, for me, the Illmatic session that I did was … in a way was a discovery that I had a vision and a voice that could be paired up with something. I just felt like I really … I was the right guy for that job and you can see it. Even at the time, I didn’t know that it was an epic record that was going to go down in history. None of us did, but it all feels like it was right.

How do you mean vision and voice?

It was the document. At that point, the artists in hip-hop were proud of where they were from. They wanted to let people know where they’re from. The record was a very cinematic record. It was about where he was from. It was about the people that are in the album packaging, the people who are hanging out with him in the projects. It was about all those things and as a lover of the document of Danny Lyon and then Robert Frank and people like that, I felt like it was my opportunity to document where this guy was from.

I’m not sure I had been in the projects before. I had never been to the Queensbridge projects up in New York City. I was seeing it with fresh eyes and I was seeing it as being something really interesting. You know?

Whereas when you’re from there it’s not interesting to you. It’s like, “Yeah, whatever.” But he wanted to represent from there. He wanted to be like, “This is where I’m from. There are where these stories are from. That’s why we need to shoot this here.”

How did you prepare to shoot that session?

I prepared with an open mind. I prepared by listening to the record and making sure I had … At the time, everything was film. Just making sure I had all my cameras ready and making sure … I got in there and my eyes were big. I was like, “Wow. There’s a lot of storytelling right here.” You’ll see if you look in the packaging I not only photographed him but I photographed his crew. Everybody was hanging out. I photographed the cops rolled up on some bicycles and I photographed that. I photographed Nas with all the little kids in the neighborhood. They all gathered around him. It’s just like I just kind of photographed a bit of everything. I just kept an open mind and realized that I had a great opportunity here.