The year was 1968, and I was driving to Los Angeles, looking for a place to stay. I pulled into the Landmark Motor Hotel, which was built in the 1950s and looked very Southern California modern. The man behind the desk looked like a character actor from a James Cagney movie—which it turned out he had been. He gave me a good rate on the only unit available, a two-bedroom suite.

I settled in and took a hit of acid. On the one hand, the job I had headed to California for had ended in less than a day. I had enough money for maybe a month, and no prospects. On the other hand, I was on my own in Hollywood, high as a kite, and for the first time in my life, I had nobody to tell me what to do. I was simultaneously scared to death and thinking, “Wow, man, look at you!”

Around midnight I stepped onto the balcony. Down by the pool, I heard a girl scream. Whenever someone is in trouble, my instinct is always to be the guy on the white horse. I hurried down the stairs. Ahead, vague figures tumbled around beside the pool. For some reason, my brain went right to rape, and I went to separate them. That’s when the girl punched me in the mouth. “We’re f–ing,” she said, “Would you please leave us alone?” I made a hasty retreat to my room, feeling more like a schmuck than a hero.

I would like to see a smile on someone’s face when they think of me.

The next afternoon I went down to the pool, where some people my age were lounging around in the shade. The girl among them asked, “Are you the guy who interrupted us last night?” She told everyone the story, and they all started laughing. Then she introduced herself. She was Janis Joplin. Lounging on pool chairs were Jimi Hendrix; Lester and Willie Chambers of The Chambers Brothers; Bobby Neuwirth, Bob Dylan’s road manager; and Paul Rothchild of Elektra Records.

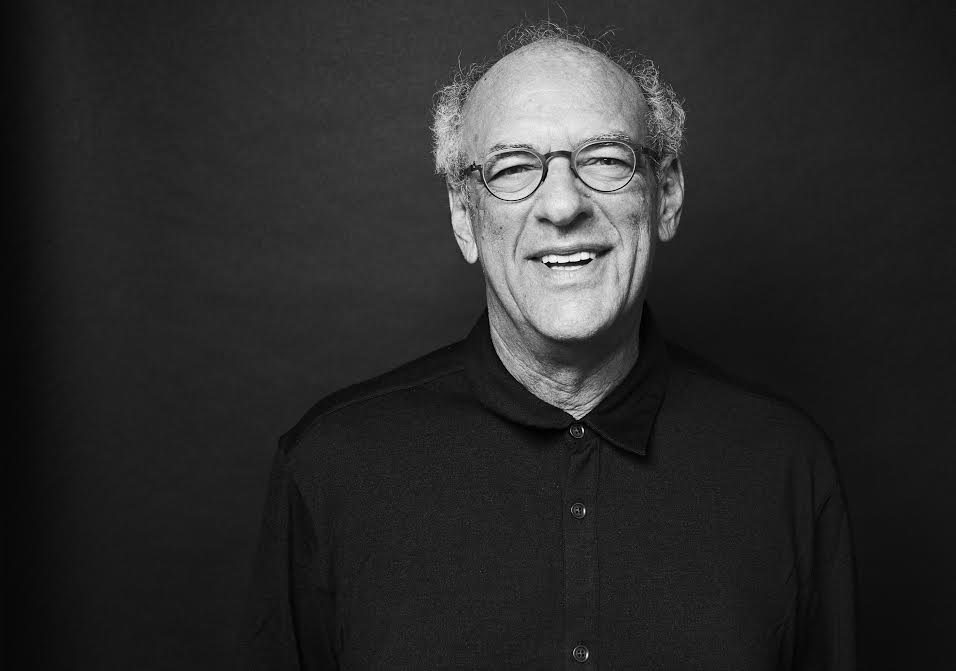

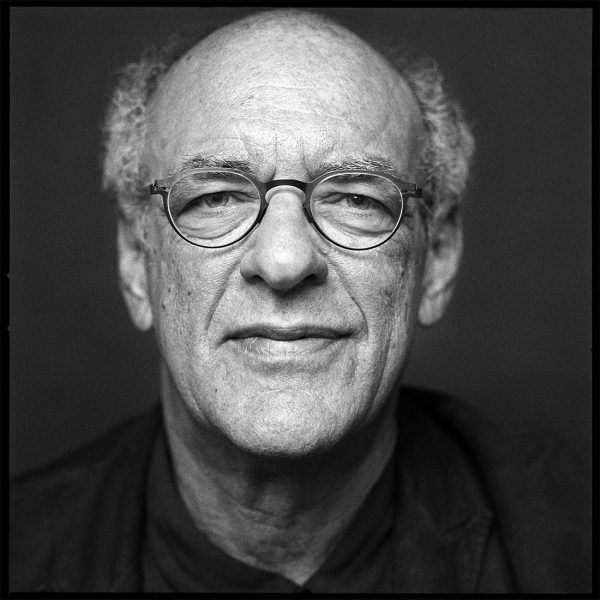

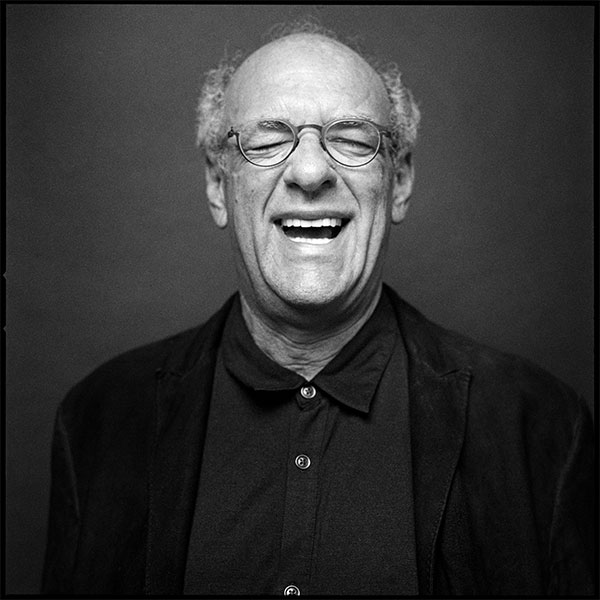

That is an excerpt from Shep Gordon’s memoir; They Call Me Supermensch: A Backstage Pass to the Amazing Worlds of Film, Food, and Rock ‘n’ Roll. After sitting poolside with Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Bob Dylan’s manager that afternoon in 1968, the then 23-year old, Shep Gordon was introduced and suggested by, Mr. Hendrix to manage an up and coming musician named Alice Cooper. Shep did. But only to use the band manager job as a cover for his pot growing and acid selling business, that was taking place at his new humble abode, the Landmark Motor Hotel. The rest of Shep’s story is equally, or even more, fantastically unbelievable, and all true.

His ability to blend uncanny compassion, trusting intuition, a little bit of good karma, and a street hustler’s mentality has lead him on a path to becoming one of the greatest influencers and connectors of modern cultural. All of that is terribly exciting, but it’s Shep’s lovable approach to it all that makes his story and ideas exciting. The guy is contagious. Whalebone was fortunate enough to catch up with the gentleman that inspires us daily to dream big.

Whalebone: Who did you look up to when you were growing up?

Shep Gordon: John F. Kennedy and Norman Lear.

WB: Who do you look up to now?

SG: Norman Lear, His Holiness The Dalai Lama and the lady in Hana, HI who started the women’s march, Teresa Shook.

WB: Highs and lows and ebbs and flows are part of life. What would say is your biggest professional success and failure?

SG: In music, the highlight was the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which was really amazing given where we came from with Alice [Cooper]. Neither one of us started doing it as a dream. He did it as a high school skit, and all the guys in the band were on the track team together. The Beatles were big then, so they went out and got wigs and made believe they were the Beatles. They’d never played an instrument or anything. I was a drug dealer who used them as a cover. The fact that we got into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 47 years later was pretty amazing. Biggest failure would be releasing the wrong Teddy Pendergrass single after his accident.

WB: If you could trade your uncanny ability to nurture talent, people and brands, for another profession, what would that be?

SG: World’s greatest doctor with the ability to cure cancer.

Photo: Jesse Dittmar

WB: We hand you a blank check, a time machine and the ability to resurrect those who are no longer with us. We ask you to return in two weeks and share with us the line-up from across the ages for the best concert of all-time…who’s on the ticket and what’s the venue?

SG: Jimmy Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Frank Sinatra, the Doors, Teddy Pendergrass and Lord Buckley all at Madison Square Garden.

WB: A piece of advice you would share with any young, creative-minded person setting out in this world?

SG: Don’t be scared of failure. Take chances. Do what feels right. Remember, we all die. Make some positive impact while you are alive.

WB: We have this friend, she’s amazing. Beyond amazing, she’s incredible. The problem is she can’t find the right guy. We are going to buy her a one-way ticket to meet you somewhere in the world for a first date. What restaurant would you take her and what is on the menu?

SG: I would take her to my place in Maui. The menu would be Maui onion and ginger soup, mushroom and white truffle risotto, brisket cooked with my grandma’s recipe, mango for dessert and we’d be drinking Cheval Blanc.

WB: Your favorite song of all-time?

SG: Wake Up Everybody by Teddy Pendergrass.

WB: What’s the coolest thing you have experienced in your lifetime?

SG: Still to come, I hope.

WB: A hundred years from now, what do you want to be remembered for?

SG: I would like to see a smile on someone’s face when they think of me.

WB: Can you recall some of the more memorable moments in your life that music and your path has allowed?

SG: For me, the great moments are transformational. It’s those moments when something changed, and that changed the way I processed everything. The first time was eating peyote in Mexico. I just got this sense that I could do anything. Before that moment, I felt like I couldn’t do anything. It completely changed the way I looked at every opportunity.

The second one, which your question sort of brought to my mind was, on the path of success you reach a place where you have to figure out how to deal with it. I used to think, is there something I can focus on? Is there a moment in my life that will immediately ground me when I’m trying to make a decision and get all the junk out of me, what success brings? All the full skull stuff. It wasn’t an overriding thought in my mind, but it was definitely there. It’s like, “I wish I had something that I could hold on to or go back to.”

Photo: Jesse Dittmar

There was a chef who was kind enough to mentor me, chef Roger Vergé, one of the great chefs in the world and creator of nouvelle cuisine. He’s a Frenchman and Legion of Honor winner. I was sort of his grasshopper. For the first year or two, every time we ate, it was his choice of where we had the meal. I would never even try to push him in a direction of a place I wanted to eat. It would be like trying to play violin for the greatest violin player in the world.

One time, when we were in the States, we discovered the restaurant he wanted to take me to was closed. So, it was on me to pick the place. I didn’t know the city very well, but I got us to a place.

WB: Had you been to the restaurant before?

SG: No. I hadn’t. The food came and it wasn’t very good. I only ate a little bit. He ate everything. Then he took my plate and also ate everything. It was a very small restaurant. The chef recognized who he was. He kept coming back. I didn’t want to start a conversation. When I went outside, I said to him, “Mr. Vergé, did you really love that food? It didn’t satisfy me at all. Could you tell me what about it was that you liked?” He replied, “Oh, Shep, it was terrible. That was a horrible meal.” I said, “If it was a horrible meal, why did you eat my plate?” He said, “Because the chef will be in the kitchen watching the plates when they come back. I did not come in here tonight to ruin his night.”

I go back to that story all the time. That, it’s not about you. A really transformative moment, particularly about making decisions. It’s very hard sometimes to clear the field and try, especially when you’re making decisions for other people, as a manager, to not bring your juju into it. Anyway, if there’s a moment in my life, that’s the moment that was transformational.

WB: How has the music industry changed over the course of your life?

SG: So many things along the way, I mean, so many. Rock and roll, particularly in the early days, it was the wild west. There wasn’t any corporate involvement. There wasn’t any real business involvement. It was basically the wild west. You had to do what you had to do to get paid. It was a different scale of economics that brought a whole different approach to it. But there were great moments.

The thing that pops into my head, that’s affected everything, in the arts at least, a rush for fame and wealth. Over the course of even my lifetime this has changed so much. The musicians who became famous in my day did so because they were the best at what they did and spent years doing it. And that’s the same thing with chefs.

Now, fame is its own category. So you look at the successful tours by new artists, and probably 50 percent of them came from American Idol. They didn’t come from the Troubadour. It’s a different kind of world. If you look back at the ’50s and ’60s and you look at the economics, nobody made anything. Alice headlined Madison Square Garden in 1972. It was $2.50 for a top ticket. Just go through the figures. It’s 18,000 seats, so maybe the place grossed with the $1 tickets and the $2.50 tickets, $35,000? Maybe Alice made $5,000, $7,500? But headlining Madison Square Garden, you couldn’t get any bigger. The only act that ever played in stadiums was the Beatles.

Photo: Jesse Dittmar

So the intentions and the motivations for those musicians were very different. Bob Dylan didn’t start because he was looking to get rich. He had something to say. These were artists who never thought they’d ever be rich. Alice was hitchhiking in 1970. I was giving rides to Jim Morrison. He didn’t have a car. Nobody had any money.

WB: There seems to be a return to American craftsmanship. And I say American, but you can put any word in there, a more natural style.

SG: Like, Shinola.

WB: Exactly, with this return to craftsmanship and craft beer, everything that is going on out there, do you think that it’s just a matter of time before music returns to where it was in the ’60s and ’70s?

SG: You know, I don’t. It’s interesting you would say craft beer because I just read a story on craft beer by the guy who founded Samuel Adams. And it was this angry article about how 90 percent of craft beers in America are owned by two beer companies. And it’s the same thing with the charts. American Idol probably owns 80 percent of the charts.

So it’s a strange time. I don’t know where we are, especially now with the new government. It’s a really strange time for the arts. It’s a little bit scary even in the culinary world as well as the musical world. Getting through the noise is hard.

WB: You’re a legend. Thank you for all of your time.

SG: Thank you. Have a great day, man.

Interview as featured in Whalebone’s Music Issue, out now. Check out the trailer to Shep’s full documentary, available for your viewing pleasure on Netflix. Thanks, Shep.